Is the integrity of Afghanistan’s central bank under threat?

Acting governor fires key staff and is accused of undoing reforms, as World Bank threatens to suspend funds

Afghanistan is one of the poorest and most dangerous places in the world, and many of its institutions are in very weak condition. Its central bank, however, appeared to be an exception. Outside officials who worked with Bank of Afghanistan (DAB) often described it as an independent institution staffed by dedicated professionals. But close observers – in Afghanistan and abroad – have told Central Banking that the DAB’s integrity may now be under threat – from the country’s own president and the bank’s current acting governor, whom the Afghan parliament voted against confirming as governor on December 2.

Reconstructing a central bank

The DAB was established in 1939, when Afghanistan was ruled by King Zahir Shah. It continued to function after Soviet troops invaded in 1978 and during the civil war that raged after they left in 1989. In 1996, the Afghan capital Kabul was taken over by the Taliban, a fundamentalist militia that went on to conquer most of the country. The Taliban took control of the central bank, but during their five years of rule, the DAB seems barely to have functioned.

The Taliban’s first central bank governor, Ehsanullah Ehsan, was a military chieftain who declared the country’s currency worthless and cancelled the order of new notes. He spent less time in the central bank than on the battlefield, where he was killed in 1997.1 The governorship passed to another Taliban fighter, Abdul Samad Sani. The Afghan currency was still unofficially circulated during the Taliban’s rule, but in much of the country, a cash economy did not exist.

In 2001, terrorists acting under the orders of Taliban ally Osama bin Laden killed several thousand people in the US. In response, the US overthrew the Taliban regime, and almost all external countries pledged to help Afghanistan rebuild.

In December 2001 and January 2002, returned Afghan exiles and a handful of international consultants re-entered the DAB’s Kabul premises. One of them was Warren Coats, then an IMF official, who has had a long career as an economic adviser reconstructing the central banks of countries emerging from war or dictatorship. He was impressed by the quality of the young Afghans who volunteered to work for the reconstituted DAB. “I loved these kids – wonderful people who wanted to raise their country up from what it had become,” Coats tells Central Banking.

A succession of Afghan professionals led the DAB. Anwar ul-Haq Ahady, who had worked as a banker and academic in the US, was governor from 2002 to 2004, before becoming the country’s finance minister. He was succeeded by Noorulah Delwari, seen by some observers as an ally of Afghanistan’s first post-Taliban president, Hamid Karzai. In 2007, Delwari was succeeded by Abdul Qadir Fitrat, a former banker in the US and IMF official, who served as governor from 2007 until 2011.

Coats worked with the DAB again when it was under Fitrat’s leadership, as an independent consultant for the IMF. He says Fitrat implemented a series of major reforms of the central bank’s structures. The new governor made redundant around 1,000 “zombie employees”, who owed their posts to political connections, Coats says: “These weren’t like ‘ghost employees’, who don’t exist – they were there, but they had no skills and they would show up and sit around and sleep and play cards.” In these years, Coats says the DAB created “a western-style HR system where people were hired based on qualifications and did not get jobs because of their ethnicity and tribe and connections, which was how it had always been for centuries. You would think that reform would take generations, but it didn’t.” This effectively changed the central bank’s culture, he says.

Under a later governor, Coats says, there was an attempt at “going back to the model of listening to MPs [members of parliament] who said they had a relative who was looking for a job. It was the younger staff of the central bank who objected to that – they made a huge fuss”.

The first years after the ousting of the Taliban regime saw the re-emergence of Afghanistan’s banking system. It was dominated by a single lender, Kabul Bank, which soon effectively gained a near-monopoly role in paying the salaries of government employees. The decisions of some international donors seem to have played a key role in this. The lender was founded by Sherkhan Farnood, who had fled Afghanistan during the Soviet occupation to become an internationally successful poker player. Farnood had run hawala, the informal money transfer agencies used by many Muslims, during the 1980s and 1990s.

Kabul Bank became the centre of one of the biggest financial crimes of the past two decades. Figures linked to that scandal continue to play an important, if often unexplained, role in Afghanistan’s government and economy.

“Kabul Bank managed to secure a $1.8 billion annual contract to pay (with international funding through the Afghan Reconstruction Trust Fund) the salaries for about 80% of the employees of the Afghan government,” wrote Arne Strand, a Norwegian expert on reconstruction in Afghanistan and other conflict-hit regions.2

The bank also earned up to $1.3 billion in deposits from ordinary Afghans. Strand calls this the result of “effective advertising”. One foreign correspondent, Jon Boome, wrote that the bank promised new depositors entrance into a lottery.

The Kabul Bank scandal

It is unclear when rumours first began circulating that Kabul Bank was an unstable and even corrupt lender. But they were common less than seven years after the Taliban’s overthrow. One prominent figure in Afghan politics, Ashraf Ghani, who was finance minister from 2002 to 2004, was convinced there was major corruption at Kabul Bank by 2008, at the latest. In a 2011 report, the then Guardian correspondent Boone said Ghani told him that year that the bank’s owners and senior managers were emptying the bank of its deposits for their own benefit. These fears were proved correct several years later.

In September 2010, news organisations reported that Kabul Bank was failing. Its collapse would have endangered Afghanistan’s fragile cash economy and impoverished its state employees. The central bank took over Kabul Bank that autumn and refinanced it using funds from the IMF and other donors. The IMF had initially refused to continue disbursing funds in Afghanistan until the crisis at Kabul Bank was resolved. In November 2011, the IMF’s executive board authorised a $133 million loan. It warned: “The IMF hopes that the programme will strengthen the hand of the economic team to push forward with difficult reform, but there are clear risks, including from vested interests that may have an interest in derailing reforms.”

There were rumours of large-scale thefts from the bank and that relatives of top government officials were involved. Several journalists, including Boone, reported that a 2012 inquiry by a joint commission of Afghan and international experts, led by Slovene anti-corruption expert Drago Kos found that around $900 million had been stolen from Kabul Bank. This was a staggering sum – around 8% of Afghanistan’s $12 billion GDP at the time.

The inquiry found that Kabul Bank’s chairman, Farnood, and its chief executive, Khalilullah Ferozi, misappropriated $579 million in deposits. They used them for a series of loans, most of which seem to have been simple transfers to Farnood and Ferozi or their allies. The ‘loaned’ funds mostly disappeared to foreign countries.

The bank’s owners were from the minority Uzbek and Tajik groups. The Karzai family are members of the Pashtun, Afghanistan’s largest ethnic grouping. Strand describes the owners as having “opted to secure for themselves political connections in the Afghan government to fully utilise the financial opportunities that the bank provided them”. The bank’s owners approached brothers of both President Karzai and his vice-president, Mohammad Fahim, a feared warlord. In one particularly questionable transaction, Kabul Bank lent $22 million to Mahmoud Karzai, one of the Afghan president’s brothers. He used the money to become Kabul Bank’s third-biggest shareholder. The vice-president’s brother Abdul Haseen Fahim also became a shareholder by a similar route, and both men sat on Kabul Bank’s board.

Farnood and Ferozi established 200 fake companies that received loans from Kabul Bank, according to later investigations. The loans were transferred to the Shaheen Exchange, a hawala established by Farnood in Dubai and then sent back to people in Afghanistan, often using fake names. “There were two sets of books, one fake set in Kabul that was made available for the auditors and one real set held by Shaheen Exchange in Dubai,” Strand wrote.

Kabul Bank bought a large number of properties in Dubai, which it then made available to Afghan political figures. The scandal eventually broke when media outlets reported that the bank was suffering huge losses on its Dubai property investments. Farnood reported the losses to the Afghan authorities and asked for a bail-out. Senior officials from the US and other foreign donors became involved in the resolution of the bank and demanded a series of investigations and trials.

Several observers, including Strand, fault the DAB for what they say were delays in investigating Kabul Bank. But once Kabul Bank had failed, the DAB was central to its rescue. But then, in late June 2011, DAB governor Fitrat fled Afghanistan for the US, saying his life was in danger after he had tried to expose the Karzai family’s involvement. The Karzai government in turn requested that he return to face corruption charges, but US authorities refused the request. Both Farnoud and Ferozi were sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment in 2014. Farnoud died in jail in 2018, officially of heart disease. Other senior figures accused of wrongdoing in the scandal, including Mahmoud Karzai, have never faced trial.

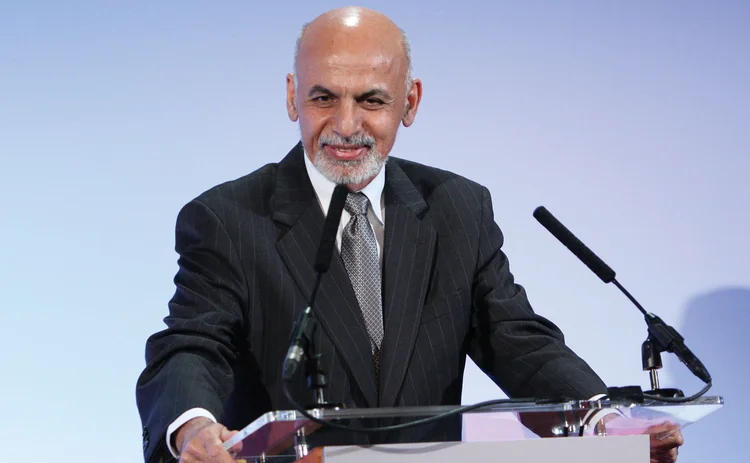

President Ghani

Ghani himself had spent most of his adult life outside Afghanistan, as an academic and then an official at the World Bank and the United Nations, before returning to the country after the overthrow of the Taliban. He became President Karzai’s chief economic adviser in February 2002, and then finance minister in June, serving two and a half years until December 2004. In 2009, Ghani stood as a candidate in Afghanistan’s presidential elections, but lost as Karzai won a second and final five-year term. Five years later, Ghani stood again and won.

After Fitrat fled from Afghanistan in June 2011, then-president Karzai re-appointed Noorullah Delwari as DAB governor. But in September 2014 when Ghani won Afghanistan’s elections and became the country’s second post-Taliban president, Delwari resigned his post within two months. Khan Afzal Hadawal became the central bank’s acting governor until 2015, when Ghani nominated Khalil Sediq to the role. Afghanistan’s parliament confirmed Sediq as governor in July that year. Sediq was a long-standing central bank official who had served as its governor from 1990 to 1991, during the civil war that followed the Soviet withdrawal.

One person who worked closely with Sediq at the DAB says that he worked to reform both the central bank and the country’s financial system: “He was very tough, very strict, and did everything within the law and based on analysis and reports. The DAB worked closely with both the IMF and the World Bank, and they were very happy with what we did.”

Sediq served until June 2019, when he announced his resignation, saying his ill health was worsening in Kabul’s notoriously polluted air.

Ghani appears to have had trouble finding a central bank governor who could be confirmed by Afghanistan’s parliament. For almost a year, DAB’s first deputy governor, Wahidullah Nosheer, served as acting governor, with Mohammed Qaseem Rahimi as the next most senior official. One person who was present says Nosheer and Rahimi essentially followed the policies and procedures that Sediq had put in place: “It went very smoothly.”

Then on June 3, 2020, Ajmal Ahmady was nominated as governor by Ghani.3 Before becoming central bank governor, Ahmady had spent 16 months as Afghanistan’s trade minister, after Ghani appointed him to the role in February 2019. While he waited for confirmation by Afghanistan’s parliament, Ahmady entered the DAB as acting governor. Ahmady is a member of the majority Pashtun ethnic group, like President Ghani himself, in a country where this remains an important factor. Ahmady is also seen by some as a close ally of Ghani, with one person close to the situation saying he was engaged to the president’s niece.

Just over three weeks after Ahmady’s appointment, Afghan media outlets reported that almost all the central bank’s most senior officials below the governor had been suspended or dismissed. Nosheer was suspended on June 22. Afghan news outlets also said three more senior central bank officials had been suspended by President Ghani for alleged corruption. One person close to events tells Central Banking Nosheer arrived at the bank to find his office locked. He was then dismissed at a scheduled meeting of the central bank’s council, consisting of acting governor Ahmady, President Ghani, the first deputy governor and four others. Under the law governing Afghanistan’s central bank, all the council’s members must be appointed by the president with the approval of the country’s parliament. “Wahid [Nosheer] was sure that Ghani would not back the central bank [acting] governor but he did,” the person close to events tells Central Banking.

Shortly afterwards, the DAB issued a statement in Dari and Pashto that four unnamed senior officials had been dismissed for what it alleged were seven cases of corruption. The central bank said that it had sent a dossier on them to Afghanistan’s Attorney General’s Office. Central Banking has confirmed with sources close to events that the four officials who were dismissed were the DAB’s second deputy governor Rahimi, its chief financial officer, Syed Younus Sadat, its director-general of procurement, Abaseen Mal, and the director of its financial sector strengthening projects department, Samiullah Mahal. Officials from the World Bank and other international donors met frequently with Mahal, a person close to the events said. Both Warren Coats and another person close to events tell Central Banking that Rahimi had been asked to resign by acting governor Ahmady. When Rahimi refused to go, both sources told Central Banking, he was dismissed by Ahmady. The other three senior officials were fired shortly afterwards.

In a second statement, also issued in Pashto and Dari, the DAB said that President Ghani supported Ahmady’s actions in sacking the officials. The dismissed officials have strongly denied all accusations of corruption in statements to local media outlets. Central Banking has spoken to someone close to these events, who says that the charges are baseless. This person alleges that acting governor Ahmady originally told the officials they had not been dishonest, and only levelled corruption charges when the officials protested against their dismissal. Central Banking has asked the DAB and the Attorney General’s Office for comments on these allegations, but has received no reply.

“The charge against Qaseem is corruption,” Coats tells Central Banking. “I’ve known Qaseem for a long time, and if he’s not clean I would be shocked. I’ve talked to a great many people and they all say he is totally honest. They are clear that he’s being fired as a political matter. It’s almost certainly because the central bank law says the only grounds for firing senior officials are if they’ve been convicted of corruption.”

Coats says he never worked with Nosheer, but that senior officials who had worked with him greatly respected him. “Everyone says he is a competent, honest guy,” Coats says. He knew Rahimi well, having first met him on a programme run by the US government development agency, USAID, which put 80 graduates through a two-year training course in the finance ministry or the central bank. “After that, they had the choice of staying at the central bank, or going elsewhere and earning more money,” says Coats. “And most of them chose to stay. Qaseem was one of them – I talked to him and convinced him to stay. He was the section head and he was a natural leader. I loved working with him. He was clearly dedicated to the standards of the bank and the quality of its work.”

Coats is unequivocal on what he believes the reasons for the corruption charges are. “There is no sign of any corruption concerning these central bank officials,” he says. “There is corruption in Afghanistan, but the authorities have no sign that these officials have done anything. This is just business as usual – the way things were done in the old days in Afghanistan. It’s a power play.”

Officials in Afghanistan, Coats says, described the new acting governor as trusting no-one outside a small group of associates, mainly of the same Pashtun ethnicity as himself. Ethnic politics were a likely factor in the breakdown of trust in the central bank, he says. “It’s a move to get rid of anyone that the right-wing, nationalist Pashtun government doesn’t like,” he adds. He notes that “Qaseem is half-Pashtun, half-Tajik”, but says this is not sufficient to gain the government’s trust.

Someone close to the situation says that Ahmady is regarded with some suspicion by officials both at foreign donors and within Afghan economic ministries. For example, when he was commerce minister he demanded that banks increase their lending without doing any due diligence on borrowers, this person says.

Several local news outlets gave a similar picture of Ahmady’s arrival at the central bank. Tolo News said some of the suspended senior officials alleged he had moved into the bank with 15 close associates. The team began giving orders to the central bank’s senior management, despite having no knowledge of its operations, the newspaper alleged.

Heads of non-governmental organisations and some Afghan lawmakers condemned the sackings at the central bank. They said that under the law governing the central bank, the governor, deputy governor and central bank council members all need parliamentary approval before being appointed. They also believe the dismissals of the senior central bank officials were politically motivated. “An acting governor should not take major decisions until he receives a vote of confidence by parliament,” Khalil Raufi, co-ordinator of Afghanistan’s Civil Society and Human Rights Network, told locally based reporters.

“The deputies of the Bank of Afghanistan are supposed to report only to the president of Afghanistan,” Wahid Farzayee, a senior member of the Afghan Lawyers’ Union, told local media sources. “But in this case, their rights have been violated.”

One person close to the events at the DAB says Ahmady may have attempted to win confirmation by reverting to a tactic commonly used before the reform of the bank’s processes: giving central bank jobs to people who were not necessarily qualified for the roles but who were close to politicians. “More than 100 people, who have not a single day of experience in banking were appointed on requests of MPs,” this person wrote in an email to Central Banking before a parliamentary vote on Ahmady’s confirmation as governor on December 2. “Some of them were appointed in very key positions. By doing this favour to MPs, Ahmady is looking for their vote of confidence in parliament.” Representatives for Ahmady and Ghani declined to comment on these allegations or on other matters raised in this article.

The acting governor has made more major changes at the central bank, this person says. “More then 10 experienced directors have been fired and more than 20 key staff have been transferred to irrelevant departments,” the person tells Central Banking. “Existing staff are demotivated and discouraged.” This person claimed that in recent weeks, the situation at the DAB had worsened. Several of the dismissed senior officials are said to be lobbying against Ahmady’s confirmation. Central Banking sent detailed questions on these allegations to the DAB in addition to seeking comment from Ahmady, but received no response. Central Banking also put the allegation that Ahmady was seeking to influence lawmakers to president Ghani’s press team, but they did not reply.

In the days before the vote, many of these allegations were widely publicised in Afghanistan. Tolo News repeated the allegation that Ahmady had recently appointed 100 people to the DAB, many unqualified but linked to lawmakers.4 The media outlet claimed that the governor had given these employees extra pay. The former head of Afghanistan’s National Directorate for Security, Rahmatullah Nabil, repeated the allegations on social media network Twitter.5 Central Banking asked both the DAB and the president’s office for comment on these allegations, but they did not reply.

On December 2, Afghanistan’s lawmakers voted decisively to reject Ahmady as the country’s central bank governor. A total of 242 lawmakers were present, Tolo News reported, meaning that nominees needed 122 votes in favour to be accepted.6 Ahmady received 72 votes. Lawmakers did not reject all of Ghani’s nominees, but instead voted to accept three out of five people whom he had named as cabinet ministers.

It is not clear how Ghani will react to lawmakers rejecting Ahmady as governor. One person close to the matter tells Central Banking that Ghani could decide to withdraw him. But he said the president might decide to keep Ahmady on as acting governor more or less indefinitely. Central Banking asked both the DAB and the president’s office if Ahmady would continue as acting governor, but they have not replied.

IMF financing

Afghanistan receives large amounts of finance from abroad, both from international financial institutions and from friendly governments, led by the US. In recent months, two important donors, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, appear to have adopted different approaches to their Afghan programmes. On November 6, 2020, the IMF said it had approved a financing programme for Afghanistan worth $370 million over 42 months. It said the programme “aims to support Afghanistan’s recovery from the Covid-19 pandemic, anchor economic reforms and catalyse donor financing”. The IMF would focus “on preserving macro-financial stability, addressing fragilities that hinder sustainable growth and poverty reduction, and advancing self-reliance”.

Factors that would be critical for Afghanistan’s development, the IMF said, included “sustained donor support, steadfast reform implementation, and progress with combatting corruption”. It said its programme envisioned “intensified financial sector oversight in the face of rising risks, reforms of state-owned commercial banks, and strengthening the central bank’s autonomy and governance as well as its regulatory and supervisory frameworks, including for AML/CFT”.

The IMF announcement made no mention of the president’s dismissals of the central bank’s first deputy governor and other senior officials.

One observer tells Central Banking that the IMF’s knowledge of Afghanistan is in some ways limited, as it no longer has a resident representative in the country. The IMF tells Central Banking: ‘Following the killing of the IMF resident representative in Kabul in January 2014, the IMF embarked on a review of the security for all locations where the IMF operates, that are considered high-risk locations, including Kabul. As a result, we no longer have a resident representative in Kabul, although we maintain an office with local staff.’

IMF officials dealing with Afghanistan tell Central Banking the IMF’s priorities in aiding Afghanistan were to help it overcome the major economic challenges it faces, from its decades of conflict and poverty, as well as the new challenge posed by the coronavirus pandemic.

The ability of central bank and other economic policy-makers to steer the Afghan economy, IMF officials note, is to a degree hamstrung by the security environment, which is perhaps the most important factor in the war-torn country. Still, improved reform implementation could help lay the foundation for stronger and more inclusive growth and thus a better future for all Afghans, they say. Afghanistan receives large foreign aid, which – including for security expenses – amounts to 40% of GDP. Donor grants are expected to fall in the coming years, the IMF officials noted, and the government will have to generate more revenue from tax and customs duties, to prevent cuts in much-needed development and social spending.

The World Bank seems to be taking a different approach to the DAB. On December 2, Tolo News said it had received a leaked letter from the World Bank to President Ghani, dated November 23. The letter allegedly said that there were two failures by the authorities that could stop the World Bank from continuing to disburse the $200 million remaining from an agreed $600 million aid package.

It allegedly said Ghani’s government must implement a new set of public investment management regulations. The letter allegedly also said the central bank must begin releasing data on the country’s banks to the World Bank.

“Unfortunately, we have not been able to obtain banking sector data from DAB despite several written requests. This data is not sensitive, and was shared with the World Bank prior to the release of funds under [the] previous Incentive Program,” Tolo News cited an unnamed World Bank official as saying in the letter. This data was needed, the World Bank official is claimed to have written, because “under our current operational policies, the World Bank is obligated to assess and confirm the adequacy of a recipient country’s macroeconomic policy framework prior to disbursing budget support funds”.

Central Banking asked the World Bank if the Tolo News report of a leaked letter was accurate, whether the World Bank was now receiving the data it had requested from the DAB and whether it had any concerns about the central bank. A World Bank spokesman referred Central Banking to an official statement issued on December 2, which effectively neither confirmed nor denied that the reports were accurate.7

“In light of recent media coverage, the World Bank would like to reconfirm its long-standing commitment to supporting the people of Afghanistan and protecting the hard-won development gains,” the statement says. “No letter from the World Bank to the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan has been released to the public.” The Tolo News story reported that the letter had been leaked, rather than released.

Extraordinary events

There are two main alternative explanations for this series of events at the DAB.

One possibility is that Ghani and Ahmady really have discovered malfeasance on an exceptional scale in Afghanistan’s central bank. If this is the case, they have yet to present evidence to support such a charge. There are no reports that Afghan prosecutors have taken any action against the four officials who resigned or were dismissed. The other possible explanation is that the president and governor have not found any wrongdoing, but are dismissing independently minded central bankers on false charges.

If the latter explanation is true, why would President Ghani behave in such a way?

Central Banking has spoken to several non-Afghan citizens who worked as technical assistants in Afghanistan when Ghani was finance minister. They speak of him as a man of integrity and intelligence who worked hard to rebuild the country’s institutions. He wrote, with the UK development specialist Clare Lockhart, a highly praised book entitled Fixing failed states. Many institutions sought his advice on post-conflict economies. Coats was one of the many people in this field who knew and respected him. “I met Ghani when he was a technical adviser to the World Bank,” he tells Central Banking. “I don’t know him well, but I found him very knowledgeable and intelligent, a technocrat.”

It appears to be unlikely that such a man should turn on economic reformers at the central bank. But Coats is convinced that this is what Ghani has done. “I heard that Ashraf Ghani is now very isolated and listening to nobody but a small group of advisers,” he says. “They appear to be telling him that he should just appeal to a very narrow kind of Pashtun loyalty that excludes all other ethnic groups in Afghanistan.”

An Afghan close to recent events at the DAB speaks in similar terms: “So many people from my family and friends voted for Ghani, for these reasons: he’s very intelligent, knows a lot, wants reforms. But now he seems to have changed – I don’t know why, but it has happened.”

Kabul Bank’s long shadow

The Kabul Bank fraud continues to crop up in the story of the Afghan economy, often in bizarre ways. There are credible allegations that figures who were closely involved in the scandal are being treated leniently, or even favoured, by Ghani’s government. For example, Ferozi, the former chief executive of Kabul Bank, was released from jail five years early in 2019.

The then-US ambassador to Afghanistan, John Bass, said on Twitter that he was “disturbed by reports the Afghan government requested early release for Kabul Bank fraud perpetrator Khalil Firozy [sic] before conclusion of his sentence. Countless Afghans suffered in the past decade because international assistance funds were stolen for personal gain.” The US ambassador continued: “This action, along with the continued failure to execute warrants for those accused of corruption, calls into question the government’s commitment to combating corruption and making best use of donors’ support.”8

Then, on June 1, 2020, Ghani announced he was appointing a new acting minister for Urban Development and Land to his government. The man given the role was Mahmoud Karzai, the brother of the former president, who had been deeply involved in the collapse of Kabul Bank. Ghani’s official representatives did not respond to questions about whether Karzai is a fit person to be a government minister. The Ministry of Urban Development and Land did not reply to questions about Karzai’s involvement in the Kabul Bank scandal.

A month later, several Afghan news outlets reported that Abdul Ghafar Dawi had been seen in the office of the central bank’s acting governor. Dawi is a businessman, who owns an oil firm that bears his name. He was also convicted of criminal charges in the Kabul Bank case by an Afghan court in November 2017, and of other charges of embezzlement and tax evasion. The court sentenced him to six years’ imprisonment, and ordered him and a close associate to repay the Afghan state $21 million in defrauded or stolen funds. Dawi appears not to have served any jail time or repaid any money.

Ahmady issued official statements confirming that he had met with Dawi. The acting governor said he had agreed to meet him only if Dawi was accompanied by his lawyer. In another statement, he said he had been tricked into meeting Dawi by an unnamed member of the Afghan parliament. The central bank’s security guards, Ahmady said, did not have the power to search the lawmaker’s car. He did not say what, if anything, he had discussed with Dawi. One local reporter said Dawi’s lawyer claimed he had been invited to the DAB by the Kabul Bank Settlement Commission. The DAB declined to comment.

These incidents, if accurately reported, make it harder to believe that Ghani necessarily takes a hard line on corruption and dismissed the senior central bank officials in an effort to root it out. The Kabul Bank scandal also underlines the importance of the World Bank’s reported request for accurate information from the DAB on Afghan banks.

Alarming signs

Afghanistan has suffered decades of conflict, and its civil war is intensifying. On November 7, 2020, three central bank employees, including the governor’s senior public relations adviser, were killed when a terrorist bomb blew up their car in Kabul. Many of its official institutions appear to suffer from high levels of corruption. Attempts to rebuild the country also means working with those who wield power in its provinces and cities. Many of those leaders have long records of violence and dishonesty. Pragmatism, in Afghanistan, is often going to mean working with such people.

But ignoring abuses appears to achieve little and carries major risks for Afghanistan. The owners of Kabul Bank and their politically well-connected friends were allowed to carry on stealing from small depositors for years – long past the point where many prominent members of Kabul’s relatively small community of economists and financiers, both Afghan and foreign, suspected something was gravely wrong. But for years, no-one in Kabul’s communities of diplomats, aid workers, intelligence officers and consultants managed to convince Afghanistan’s donors to act. The Kabul Bank scandal ended up costing $1 billion in a country where, two years ago, GDP per capita was estimated at $520, or just over $1.50 a day.

The IMF and the World Bank are in a difficult position in Afghanistan. The IMF aims to support the government as it attempts to cope with a long-running war, the Covid-19 pandemic, a severe recent drought, the devastation of most of its institutions. The fund projects that Afghanistan’s GDP will contract by 5% in 2020. For the IMF to deny funds to the Afghan government during these crises would be problematic. The World Bank faces a similar dilemma, but may be responding differently. If recent reports in the Afghan media are correct, the World Bank is ready to withhold aid to Afghanistan unless the central bank releases banking data to it.

There could be very large costs if the reforms of the central bank are reversed, says central bank reconstruction veteran Coats. Afghanistan’s central bank, he argues, as with many developing economies, is its “most advanced institution – not that it’s all that advanced, but it’s the most advanced that they’ve got. So, if they have problems, it’s a big deal”.

Notes

1. Ahmed, Rashid, Taliban: militant Islam, oil, and fundamentalism in central Asia, second edition (New Haven; Yale University Press, 2001).

2. ‘Elite capture of Kabul Bank’, by Arne Strand, 2014; chapter in Corruption, grabbing and development – real world challenges, edited by Tina Søreide and Aled Williams (Cheltenham; Edward Elgar Publishing, 2013).

3. Afghan names are often transliterated from Dari or Pashtu into English in several different ways. For example, Ajmal Ahmady is sometimes referred to as Ajmal Ahmadi.

4. Tolo News, Central bank chief gave extra income to appointees: documents, December 1, 2020.

5. Tweet by Rahmatullah Nabil (@RahmatullahN), December 1, 2020.

6. Tolo News, Parliament approves 3 of 5 ministers, votes out central bank head, December 2, 2020.

7. World Bank, World Bank Afghanistan statement, December 2, 2020.

8. The Twitter link now gives the name of the person tweeting as chargé d’affaires Ross Wilson, but it was John Bass who issued the statement in August 2019.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: subscriptions.centralbanking.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com test test test

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com test test test