Trends in reserve management: 2024 survey results

Executive summary

Trends in reserve management: 2024 survey results

RMB – internationalisation is not over

Managing the tides: the dynamic history and future challenges of Korea’s foreign reserve diversification

Interview: Jonas Stulz

Reserve management at the National Bank of Slovakia

The NBP’s gold purchases – a view from the risk management trenches

Appendix 1: Survey questionnaire

Appendix 2: Survey responses and comments

Appendix 3: Reserve statistics

This chapter reports the results of a survey of reserve managers that was conducted by Central Banking Publications in January and February 2024. This survey, which is the 20th in the annual HSBC Reserve Management Trends series, was made possible by the support and co-operation of the reserve managers who take part in it. The reserve managers contributed on the condition that neither their names nor those of their central banks would be mentioned in this report.

Summary of key findings

- Geopolitical escalation is the most significant risk that reserve managers face in 2024. Following the eruption of the war in Gaza that threatens to destabilise the Middle East and Red Sea supply chains, globally, reserve managers voted it their most pressing concern, and one that can trigger inflationary and energy shocks. Reserve managers also discussed the ongoing war in Ukraine and geopolitical tensions over Taiwan.

- In a marked shift from 2023, over the last 12 months, most central banks increased the duration of their reserves portfolio, expecting the end of the monetary policy tightening cycle. Forty-six out of 87 central banks (52.9%) made this decision. In contrast, last year, 44 out of 78 central banks (56.4%) said they had reduced duration to limit the impact of higher yields in long-term maturities.

- Bond market volatility and dislocation is expected to be a key source of risk in 2024–25 due to inflation data surprises. Globally, reserve managers voted US monetary policy error as their second most significant risk. It emerged as the top concern among central banks in the Americas and Asia-Pacific.

- In response to geopolitical risks, reserve managers made changes to the location of their investments, currencies invested in and with respect to counterparties.

- Most reserve managers agreed de-dollarisation is increasing, but on a gradual basis. While no central banks expect the renminbi’s share of global reserves to reach 10% or higher by the end of 2024, by 2035, 22 central banks expect it to reach at least 10%. Nevertheless, the renminbi’s share of global reserves is still expected to remain between 4–12% in 2035, by 81.3% of respondents.

- Of the 85 reserve managers that answered the question on whether reserve levels or adequacy measures are sufficient to invest in non-traditional or riskier asset classes, 50 (58.8%), said “No”.

- Many central banks have experienced losses since 2021, and face the risk of further devaluation. Although last year central banks said this did not affect how they reported their annual results, 31 (34.8%) of reserve managers this year said balance sheet losses have, however, impacted how they manage their reserves.

- Overwhelmingly, reserve managers view the potential of artificial intelligence (AI) positively, with 82 out of 88 (93.2%) agreeing that they think it will help to optimise their portfolios in areas such as rebalancing strategies, risk-adjusted returns and tax efficiency.

- Advanced economies are much more likely to incorporate socially responsible investing (SRI) into their investments than those in emerging and developing economies. Of 28 advanced economy central banks, 23 (82.1%) said they incorporate SRI into reserve management. In contrast, 22 out of 61 central banks in emerging and developing economies that addressed this question said they incorporate SRI in reserve management (36.1%). However, most central banks only consider between 1–10% of their reserves to be SRI.

- The Canadian dollar, Swedish krona and onshore renminbi investments emerged as the currencies with the most central banks considering investing in them now, closely followed by the Australian dollar and Danish krone.

- In terms of digital assets and currencies, although no central banks are considering investing now, a small group of reserve managers (13, or 15.9%) said they would consider investing in 5–10 years.

- Interest in inflation-linked bonds has remained stable year on year. Last year, 33 (43.4%) central banks said they were investing in inflation-linked bonds, and 13 (17.1%) said they were considering making an investment imminently. This year, 39 (44.8%) said they hold inflation-linked bond investments, and 10 (11.49%) central banks said they are currently considering making an investment.

- Most central banks use derivatives for hedging purposes – 52 out of 59 central banks (88.1%) that use derivatives and answered the question limit risk in this way.

- Six central banks are considering increasing their investments in equities in the next 12 months. Two are in the eurozone, two are in Europe but do not use the euro as their national currency, one is in the Asia-Pacific region and one is in the Americas.

- Last year, higher interest rates in the eurozone increased the euro’s attractiveness as a reserve currency. This year, of 67 central banks that responded to this question, 41 (61.2%) said they thought the euro has become more appealing. In 2023, 62 out of 71 respondents (87.3%) said the euro had become a more attractive currency. Reserve managers cited interest rate differentials and weak growth prospects as factors against euro holdings.

- A slightly higher proportion of central banks reported making onshore investments in renminbi as compared with last year. Forty-seven out of 84 central banks (56%) versus 39 out of 76, or 51.3%, last year said they had incorporated renminbi into their reserves in this way.

Profile of respondents

The survey questionnaire was sent to 152 central banks in January 2024. By February, 91 central banks had sent their feedback, up from 83 last year. These institutions jointly manage over $7 trillion. This represents 65% of total global reserves in the fourth quarter of 2023, according to the International Monetary Fund’s Currency composition of official foreign exchange reserves (Cofer) survey. The average reserve holding was $83 billion. Breakdowns of the respondents by geography, economic development and reserve holding can be found in the tables below. The term ‘eurozone’ refers to the group of 20 central banks whose national currency is the euro, as well as the European Central Bank. The term ‘Europe’ refers to all other central banks in the region.1

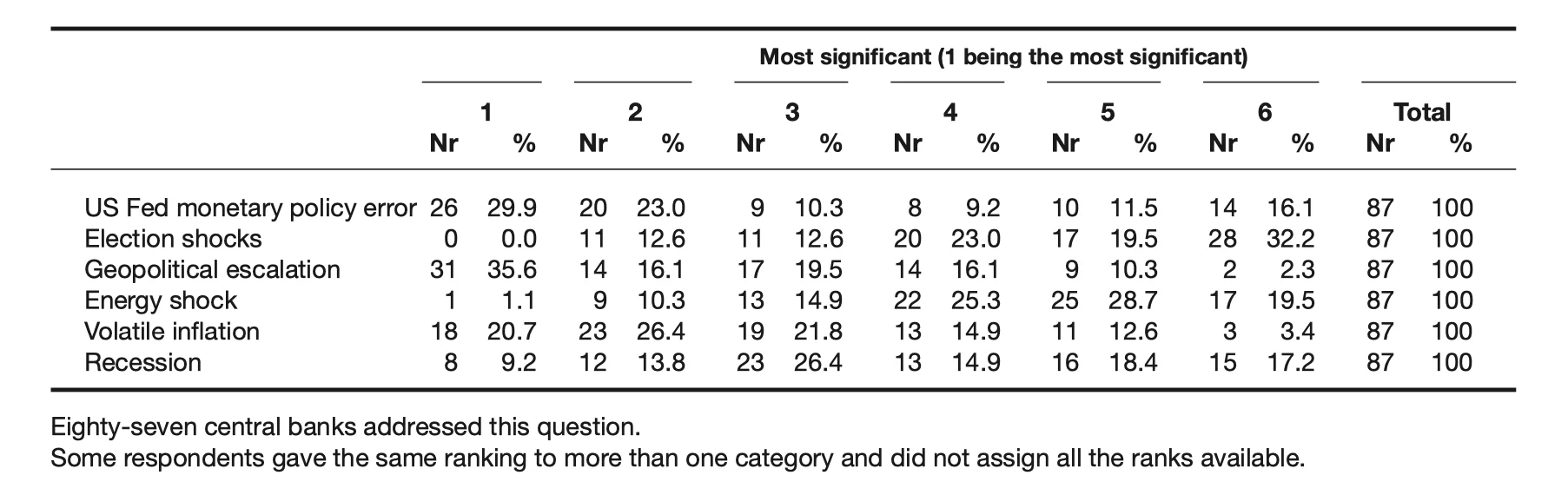

Which in your view are the most significant risks facing reserve managers in 2024? (Please rank the following 1–6, with 1 being most significant.)

Geopolitical escalation is the most significant risk that reserve managers face in 2024. Following the eruption of the war in Gaza that threatens to destabilise the Middle East and Red Sea supply chains, of 87 respondents to this question, 31 (35.6%) voted it their most pressing concern.

“The Israel-Hamas war, with the resulting attacks by the Houthi rebels on vessels passing through the Red Sea, can affect the global economic landscape and impact reserves,” said one official from a lower-middle income central bank in Africa. “Geopolitical escalation, in particular over Taiwan, could significantly impact global growth trajectories and supply chains,” agreed another official from a high income central bank in Europe.

This marks a shift from last year. Despite unprecedented sanctions on the Bank of Russia’s reserves due to the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, of 79 central banks, only 13 (16.5%) had said geopolitical risk was their main concern.

The risks reserve managers face are linked. “We think that geopolitical escalation is the most significant risk, because it can be a trigger for many other risks like energy shock, inflation and a need for bigger fiscal stimulus,” said an official from a high income central bank in Europe. An official from another high income central bank in Europe agreed, saying that geopolitical tensions can trigger energy shocks that would “put additional pressures on central banks to revisit the trajectory of their monetary policy rates”.

Globally, the next most significant risk is US Fed monetary policy error, which 26 reserve managers (29.9%) ranked first.

Analysis by geography shows that reserve managers in the Americas were more likely to rank US monetary policy error as the most significant risk they face. So, too, were central banks in the Asia-Pacific. None of the respondents in the Middle-East put geopolitical escalation as their most significant concern, although it remains the top concern among reserve managers in Europe. Central banks in Africa were most concerned about volatile inflation. Among the central banks with over $100 billion in reserves, US monetary policy error also emerged as the most significant perceived risk.

In a year in which half the world goes to the polls, a reserve manager from a lower-middle income central bank in Africa said that the US election is likely to “have implications for US economic policies especially with the possibility of the [return] of Trump”. However, an official from an upper-middle income central bank in the Middle East countered that, as Fed governor Jerome Powell’s term will end in 2026, they “do not expect a significant change in [the] Fed’s stance in 2024”. An official from a lower-middle income central bank in the Americas warned: “We believe the Fed might be tempted to ease monetary policy for political reasons while inflation is not fully under control.”

Around one-fifth of reserve managers (18, or 20.7%) globally view volatile inflation as the most important risk facing reserve managers this year, putting it in third place. The order of geopolitical tension, US Fed monetary policy error and volatile inflation holds when votes for the top three rank positions are added.

A factor that “is not on your list”, the official from the lower-middle central bank in the Americas added, “is the fiscal situation in the US”, which “could cause issues on the bond market”. Additionally, “last but not least”, a hard landing scenario would impact high-beta currencies – those that exhibit high volatility – an official from a high income central bank in Europe said.

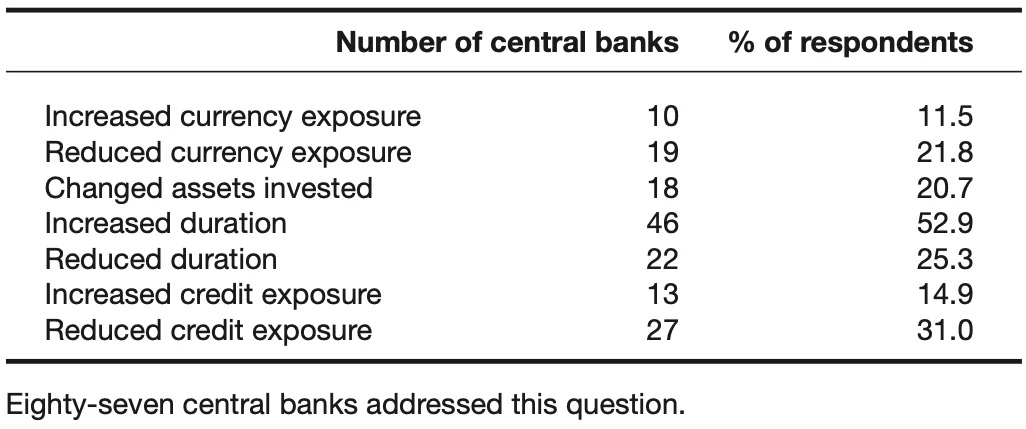

In the past 12 months, how have you positioned your reserves portfolio, given interest rate and other market dynamics? (Please tick as many as appropriate.)

In another shift from the findings last year, over the last 12 months, most central banks, 46 out of 87 (52.9%), increased the duration of their investments. “We were expecting the end of the tightening cycle in major economies,” an official from an upper-middle income central bank in the Americas said.

In contrast, last year, 44 out of 78 central banks (56.4%) said they reduced duration to limit the impact of higher yields in long-term maturities.

An official from an upper-middle income central bank in Africa explained that they “increased portfolio duration over the past 12 months to position the portfolio for rate cuts” to lock in yields on longer tenors and avoid reinvestment risk. An official from a eurozone central bank said: “As our portfolios are mostly euro-denominated, we have increased the amounts invested significantly. That involved of course a lengthening of the duration profile.”

Nonetheless, this year, around one-quarter of central banks (22, 25.3%) said they shortened the duration of their portfolio. “We reduced duration while the certainty of future rate hikes was still in effect,” said an official from a lower-middle income central bank in the Americas. Similarly, an official from an upper-middle income central bank in the Middle East said: “We reduced the duration of our portfolios during the monetary tightening period that covers most of the past 12 months, but recently we started increasing the durations as a result of rate cut expectations.”

Although 27 (31.0%) reserve managers said they reduced their credit exposure, around half fewer (13, 14.9%) said they increased it. One reserve manager from a lower-middle income jurisdiction in the Asia-Pacific said the central bank “reduced credit exposure after the banking crisis in the US”.

In contrast, an official from an upper-middle income central bank in Europe said it decreased the interest rate sensitivity of its investments by positioning on the shortest part of the curve through “slightly increasing” credit exposure using short-term money market instruments. An official from an upper-middle income central bank in Africa said “credit exposure has been increased slightly for an additional yield pick-up versus USTs [US Treasuries]” using assets with an investment-grade credit rating.

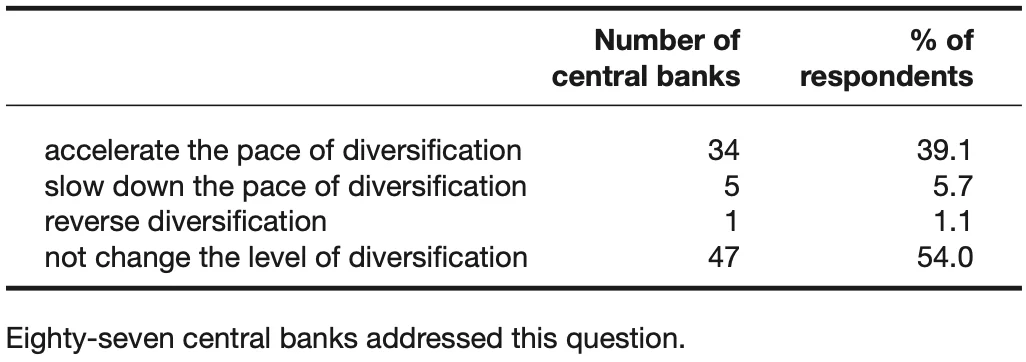

Do you anticipate that over the next year reserve managers broadly will:

Of the 86 central banks that addressed this question, 33 (38.4%) said that, in the current market environment, they expect other reserve managers will accelerate the pace of diversification. Fewer reserve managers (11, or 12.8%) said they expect others to slow the pace of acceleration down, but continue with the strategy nonetheless.

“After the different shocks to the global economy since the start of the pandemic that increased risk aversion, we expect the diversification trend to resume,” an official from a high income jurisdiction in the Americas said. “Also, this is consistent with the overperformance of short-term US Treasuries since 2022, making, in our opinion, some emerging markets [EMs] underpriced under a risk-return perspective.”

Agreeing that diversification will accelerate when there is “higher correlation between assets”, an official from a high income jurisdiction in Europe said that “diversification strategies can help achieve better performance”, at least by protecting portfolio market value.

If central banks start to cut rates this year, entry points into fixed income will become more expensive, which may also warrant diversification, an official from an upper-middle income central bank in Africa said.

“Expect diversification away from [the] US dollar as the Fed cuts rates,” said an official from another upper-middle income African central bank.

Around half of respondents (40, or 46.5%) said they do not anticipate other reserve managers will change their level of diversification. “Next year, there could be opposing forces that impact the level of diversification,” said an official from an upper-middle income central bank in the Americas. In their view, driving acceleration is “the trend of investing in ESG [environmental, social and governance] bonds”. Against, are high interest rate levels “that discourage investing in non-traditional assets”.

Volatility across markets in which central bankers typically invest is still high, which does not normally encourage conservative investors to seek further diversification, a reserve manager from an upper-middle income central bank in the Americas said. “In a situation with many different growing risks coming together, instrument diversification is not the best strategy,” an official from an upper-middle income European central bank agreed.

An official from a lower-middle income central bank in the Asia-Pacific said they expect other central banks to “not change the level of diversification, but await better opportunities to invest”.

A minority (2, or 2.3%) of reserve managers said they expect diversification to reverse. “As the global economy cools and risk of recessions comes into play, we expect portfolio managers to move into typical safe-haven assets,” said an official from a lower-middle income central bank in Africa.

For your portfolio, do you anticipate that over the next year you will:

Reserve managers generally expect other central banks will have similar approaches to diversification as themselves. Indeed, an official from an upper-middle central bank in the Americas said they anticipate their reserve managers will act “in line” with what they expect of other central banks.

Forty-seven (54.0%) reserve managers said they do not anticipate changing the level of diversification of their own portfolios, but 34 (39.1%) said they will accelerate it. Five (5.7%) said they will slow down the pace of diversification. Just one (1.1%) said they will reverse diversification.

An official from a lower-middle income central bank in Africa that does not anticipate a change in the level of diversification of its portfolio said it will likely “add more emerging market sovereign debt over the next year”.

A reserve manager from an upper-middle central bank in Africa said the central bank is unlikely to change its own level of diversification, although it expects others to accelerate theirs, because the central bank was already focused on the strategy over the past year.

They explained: “Over the past 12 months, while we have increased our exposure to USD, we diversified the portfolio across asset classes and geographical regions. On portfolio positioning, we have been cautiously adding duration.” They also said that, “although the market has priced in several rate cuts for 2024, geopolitical fragmentation may add to inflationary pressures, and hence policy rates could stay above pre-pandemic levels”. In their view, “greater geopolitical volatility and the rising number of conflicts worldwide have increased global uncertainty, hence diversification remains key”.

A reserve manager at a high income institution in Europe that expects to accelerate the pace of its diversification said its strategy “is not about starting with new asset classes – it is more about finding better ratios among the existing ones”. This central bank is not in the eurozone.

At another high income European central bank, during “recent turbulent times, hoarding euro liquidity” was its reserve management operations’ main objective. An official said that they expect the pace of their diversification to slow down because the central bank stopped reinvesting some of its non-euro exposures.

Do you expect bond market volatility and dislocation to be a key source of risk in 2024–25?

A significant majority of reserve managers expect bond market volatility and dislocation to be a source of risk in 2024–25 (70, or 80.5%).

If “Yes”, what do you think will be the main reasons? (Please select the top three and rank them, with 1 being most significant.)

The 70 reserve managers that said they expect bond market volatility and dislocation to be a source of risk ranked their top three reasons from five possible options. Inflation data surprises came first (55, or 75.3%), US Treasury supply second (30, or 42.9%) and a financial stability event third (23, or 32.4%).

“For the last couple of quarters, it has become clear how the ‘data-dependency’ discourse inflicted several episodes of very high intraday volatility in major sovereign debt markets, notably in the US market,” an official from an upper-middle central bank in the Americas said. “Until [there’s] clear indication from policy-makers that they are headed towards a consistent stance with the new interest rate cycle, any minor data related to economic activity, inflation or debt level may cause large response movements from market participants.”

An official from a high income central bank in Europe said: “Rate volatility will remain high, driven by large uncertainties in inflation development, diverging central bank policies and the effects of declining excess liquidity coupled with higher refinancing needs.”

Regarding the US Treasury supply, while bonds offer attractive returns, “the sheer size of debt issuance could be an issue, given the demand profile has significantly changed” after the Fed reduced its balance sheet, said a reserve manager from an upper-middle income jurisdiction in Africa.

In terms of a financial stability event, geopolitics and deglobalisation have accelerated global fragmentation, and the emergence of competing geopolitical and economic blocs has led to structural market risk, an official from an upper-middle income central bank in Africa said.

Another official, from an upper-middle income central bank in the Americas, said it is possible that the financial and economic consequences of a rapid rise in yields “are not totally absorbed by banks and other players”. In their view, other risks to financial stability include “exogenous” events such as cyber attacks on the infrastructure of the global financial system.

An official from an upper-middle income central bank in the Middle East said that they see financial stability risks as mainly emanating from credit and housing markets in China. Although some eurozone countries have high public debt ratios, in the reserve managers’ view, “this will not create an important market event in 2024”. This is because the “European Union decided to ask for a gradual debt-reduction plan”, which takes into account country-based differences in fiscal positions, public debt and economic challenges, as well as financing needs for a green transition.

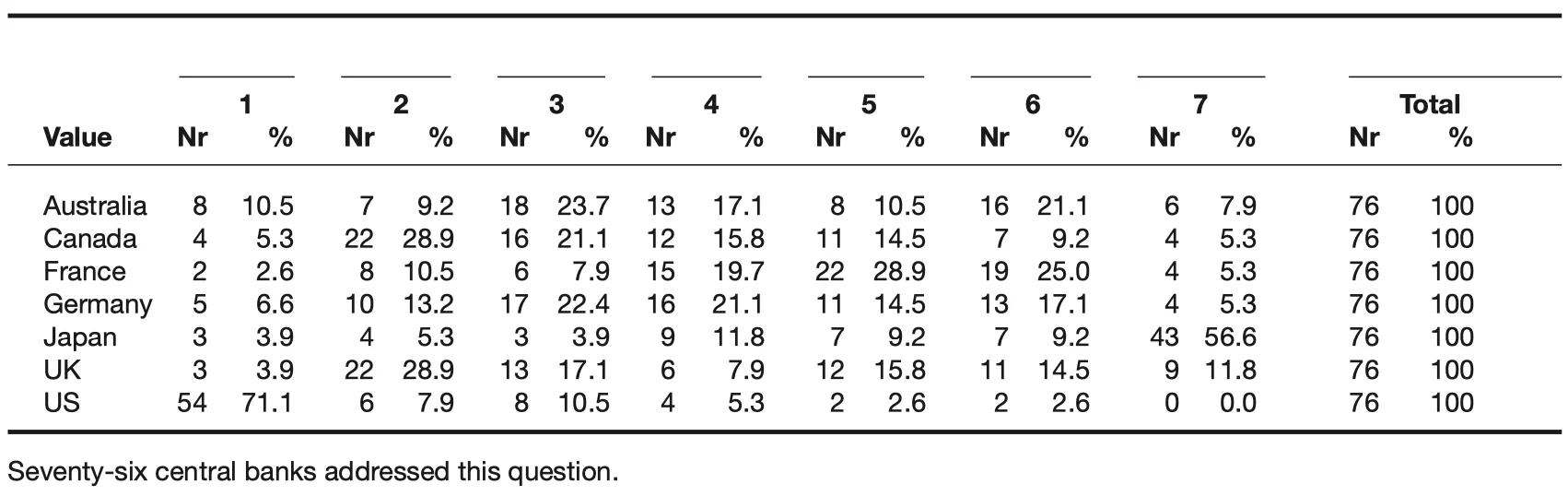

Which of the below countries’ bond markets do you think will see relative outperformance/underperformance? (Rank in order 1–7 which market you feel will outperform the most, with 1 being the best-performing.)

Reserve managers were clear that they think US bond markets will outperform relative to other Group of Seven countries in 2024–25. A majority ranked the US first (54, or 71.1%). Reserve managers were equally clear about Japan relatively underperforming – 43 (56.6%) ranked it last.

Canada and the UK ranked joint second by mode in the category. Canada emerged slightly ahead when first and second rankings were added; although behind Japan, the UK bond market was voted as least attractive in the last category. Adding votes in previous ranks together, Australia was fourth, Germany fifth and France sixth.

Are geopolitical risks incorporated in your risk management/asset allocation decision-making?

Most reserve managers, 59 (67.0%), incorporate geopolitical risks into their risk management and asset allocation decision-making.

Central banks in the eurozone are least likely to incorporate geopolitical risks into their reserve management and asset allocation decision-making. Europe refers to central banks in the region outside the eurozone.

If “Yes”, which areas of your reserve management are impacted?

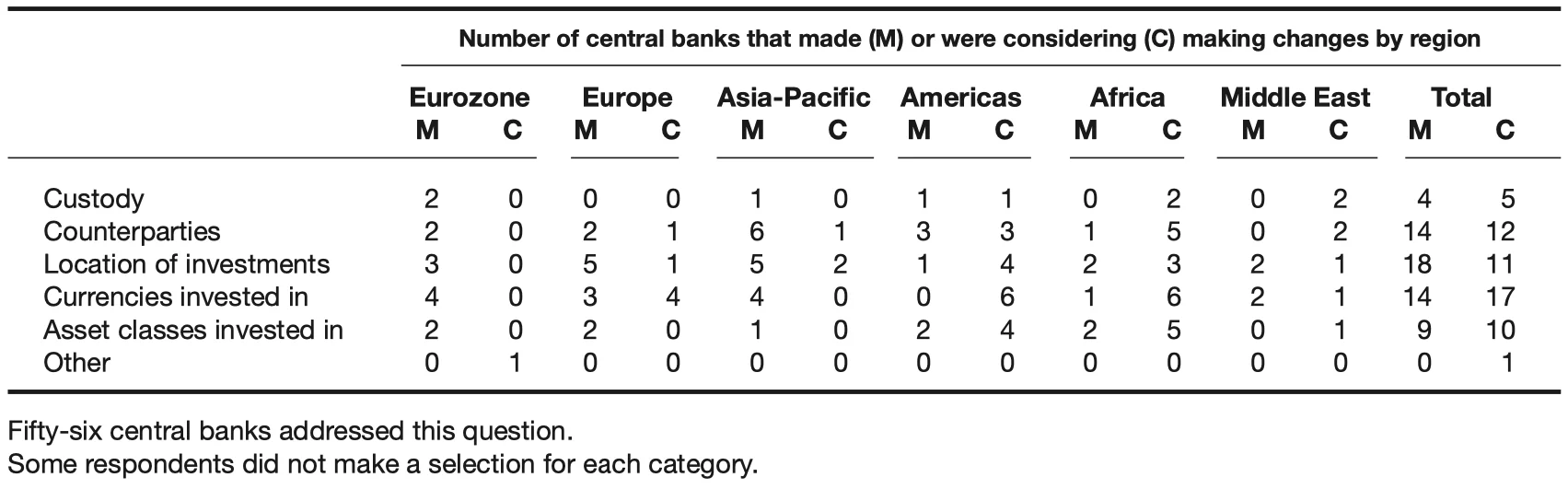

Thirty central banks made at least one change to their reserve management as a result of geopolitical risks, and 25 are considering making changes. “In most cases, the areas are interconnected. Therefore, one change implies change in other areas,” said an official from a high income European central bank.

Reserve managers most commonly made changes to the location of investments (18, or 43.9%), followed by changes with respect to their counterparties (14, or 32.6%) and the currencies invested in (14 or 31.1%). Percentages for the same number of central banks differ, as some respondents did not make selections for all parts of the question. Nine (22.0%) central banks changed the asset classes invested in and four (11.4%) made custody changes.

“We continuously assess our investments for geopolitical risks, which recently has led to divestment from issuers and a currency,” said a reserve manager from a high income central bank in Europe. Another official, from an upper-middle central bank in Europe, said: “We have made some tactical decisions by avoiding investments in certain regions affected by geopolitics”.

“During periods of heightened geopolitical risks, moratoria are put in place on those counterparties that may be impacted,” said a reserve manager from an upper-middle income central bank in Africa. An official, from a high income central bank in the Americas, said it applies “eligibility changes on some counterparties if geopolitical risks involve them”.

Globally, the most common areas in which central banks are considering making a change are currencies invested in (17, or 37.8%), counterparties (12, or 27.9%), the location of investments (11, or 26.8%) and asset classes invested in (10, or 24.4%).

Geographical analysis reveals that, although no central banks in the Middle East voted geopolitical escalation as the top risk facing reserve managers in 2024, all three said they incorporate it into their risk management and asset allocation decision-making. Two have already made changes with regard to the location of their investments and currencies invested in, with the third considering changes. Two are also considering changes with regard to custody and counterparties.

Among respondents in the Asia-Pacific, central banks were most likely to have made changes with respect to their counterparties, with six reporting having done so.

The most common changes that central banks in Europe have made is the location of their investments, driven by the decisions of central banks both in and out of the eurozone. Five central banks outside the eurozone and three in the eurozone said they made this decision. The most common area in which European central banks outside the eurozone are considering making changes is to currencies invested in, with four reporting they are currently making this re-evaluation. Four eurozone central banks have already made this change.

In the Americas, central banks are more likely to be considering making changes in the future than having made them yet. The most common area in which reserve managers are considering making changes are in currencies invested in. Six central banks said a future change in this area is a possibility. Central banks in Africa and the Americas are most likely to be considering making changes to the asset classes they invest in.

Although an upper-middle income central bank in the Americas answered “No” to this question, an official said: “We believe that the risk management approach does take into account geopolitical risk via the existence of minimum credit ratings. If counterparties, for example, are negatively affected by a geopolitical event, this should be reflected in their credit ratings.”

There is much debate and speculation about increasing de-dollarisation. Do you agree?

Most reserve managers agreed de-dollarisation is increasing, but on a gradual basis (64, or 75.3%). Eighty-five reserve managers answered this question. Nineteen (22.4%) said they do not think de-dollarisation will increase. A small minority (2, 2.4%) of reserve managers said de-dollarisation is both increasing and they think the pace will accelerate. The view that de-dollarisation will continue, albeit slowly, remained the most dominant perspective by geographical analysis.

“The process of de-globalisation, started several years ago, is creating political polarisation which might contribute to changes in the global financial system as well,” said an official from an upper-middle income central bank in Europe.

An official from a lower-middle income central bank in the Americas said: “De-dollarisation has become part of the policies and strategies of different countries to promote a more democratic international economic order.”

“Realised and potential geopolitical conflicts have created a tendency for some countries to decrease their assets in USD and move to other reserve currencies to limit their political risks,” said an official from an upper-middle income central bank in the Middle East. They added that, “despite some selloff recently, CNY has become an alternative reserve currency through China’s leading position in global trade and swap lines that central banks built with China”.

This reserve manager added that, in the event of “many developing countries” now trading with each other in their local currencies, swap lines built for this purpose have decreased the need for USD holdings in reserves. Further, an “increase in gold reserves that provide protection in volatile periods may also add to a decrease in USD holdings”.

“US sanctions on Russia have made some countries wary about being too dependent on the currency,” said an official from an upper-middle income central bank in Africa. The USD is also losing some influence in oil markets, where more sales are now being transacted in non-dollar currencies, “as a strong US dollar is becoming more expensive for emerging nations”.

“For countries with difficult relations with the US, the USD is not the same safe-haven currency as in the past,” said an official from a high income central bank in Europe. Furthermore, federal government credit-rating downgrades and political debate over the US budget “have increased the risk premium”. However, although “the global tendency for increased fragmentation”, a focus on independence and the reorganisation of supply chains have led to a lower use of the USD, they conclude that “it remains difficult to replace the USD as a dominant reserve currency”.

Are your reserve levels/adequacy measures sufficient to invest in non-traditional or riskier asset classes?

Of the 85 reserve managers that answered the question on whether reserve levels or adequacy measures are sufficient to invest in non-traditional or riskier asset classes, 50 (58.8%), said “No”.

“Non-traditional or riskier asset classes are still not permissible while we still build towards an adequate level of reserves,” said an official from an upper-middle income central bank in Africa.

“[The] reserves adequacy level of the central bank has decreased. That’s why our plans to invest in non-traditional asset classes, like equities, have been postponed,” said an official from an upper-middle central bank in Europe.

Of the 35 central banks that can invest in riskier assets, 13 are in the eurozone and six are in Europe but outside of the eurozone. Of the other 16, six central banks that said they are able to invest in riskier assets are in the Asia-Pacific region, six are in the Americas, three are in Africa, and one is in the Middle East.

By income, 22 high income central banks have this diversification option, four of which are outside Europe and the eurozone. Nine upper-middle income central banks and four lower-middle income central banks also said they are able to invest in riskier assets.

Does your central bank tranche its reserves in different portfolios?

Seventy out of 89 central banks that answered this question (78.7%) said they tranche their reserves.

How do you allocate your reserves across tranches?

Reserve managers were asked about their asset allocation across liquidity, working capital and investment tranches and 58 central banks with this structure provided data. For the liquidity tranches, the range was 0–100%. It was 0–90% for the investment tranche, 0–63% for the working capital tranche and 0–50% for “Other”.

The investment tranche had the highest average allocation at 41.8%, the liquidity tranche’s average was 38.2%, the working capital tranche average was 12.2%, and average in the ‘Other’ tranche was 7.0%.

Some reserve managers with this tranche structure explained the relationships between them. An official from a high income jurisdiction in Europe said that the liquidity tranche ensures the replenishment of the working capital tranche, and covers unforeseen foreign currency outflows from reserves. “Prudent interest rate risk management recommends the establishment of sufficiently large liquidity tranches in euros and US dollars with short durations” to cover the central bank’s short-duration liabilities and “the direct relationship” between the fixed income portfolio’s duration and “the volatility of its market value”.

Another official from an upper-middle income central in Africa explained that their working capital tranche “has a one-month investment horizon” and “holds mostly money market instruments and cash to meet day-to-day transactional needs”. The liquidity tranche “has a 12-month investment horizon, and holds mostly US Treasuries”. All excess reserves are managed in the investment tranche with a five-year investment horizon, “which gives the reserves management team and external managers more flexibility to invest across different asset classes and currencies”.

Some reserve managers said that the nomenclature of their tranches differs. For example, a lower-middle income central bank in the Americas has “liquidity, liability and investment tranches”. Another official from a high income European central bank said it has “liquidity, money market and investment tranches.”

“Other” tranches specified by reserve managers include a gold tranche, an intermediation tranche, an SDR (special drawing rights) allocation tranche and a liability tranche.

An official from a jurisdiction that is under a free-floating foreign exchange regime said the central bank has limited liquidity needs: “In consequence, we feel that integrated portfolio management is more efficient than tranching, as it allows for consolidated risk exposure monitoring and performance analysis.”

Have balance sheet losses impacted how you manage your reserves?

Many central banks have experienced losses since 2021, and face the risk of further devaluation. Although last year central banks said this did not affect how they report their annual results, 31 (34.8%) of reserve managers this year said balance sheet losses have, however, affected how they manage their reserves.

“Balance sheet losses have impacted how we manage our reserves. These losses have prompted a comprehensive review of our strategic asset allocation [SAA],” said an official from a lower-middle income central bank in Africa. “This proactive approach ensures a more resilient and adaptive investment framework.”

Another official from a lower-middle income central bank, in the Americas, said: “Unrealised losses have brought some unwanted volatility to the central bank’s capital.” This has triggered “several discussions” at the central bank “on the necessity to reduce the level of risk in the reserves portfolio”. An official from an upper-middle income central bank in Africa said it reduced its allocation in non-traditional assets.

In an increasing yield environment, “the negative mark-to-market impact on the fixed income portfolios” led officials at a high income central bank in Europe to engage “more actively in FX trades”.

At another high income jurisdiction in Europe, “in order to reduce the impact of unrealised losses on [the] profit-and-loss account”, the central bank “set up a held-to-maturity portfolio”. Similarly, an official from an upper-middle income jurisdiction in Africa said: “The central bank also started managing both a hold to maturity book and a separate portfolio where trading (sale of securities) is allowed.”

In contrast, “our accounting rules do not allow balance sheet losses”, a reserve manager from a high income jurisdiction in the Americas said.

Although an upper-middle central bank jurisdiction in the Americas said it had experienced losses in 2021 and 2022 “due to market conditions”, the central bank recently modified its SAA according to “changes in market expectations, not due to losses in those years”.

Similarly, “more precisely, expectations of balance sheet losses have impacted how we manage our assets”, an official from a high income central bank in Europe said.

Do you think artificial intelligence will help reserve managers to optimise their operations?

Overwhelmingly, reserve managers view the potential of artificial intelligence (AI) positively with 82 (93.2%) agreeing that they think it will help reserve managers to optimise their operations. Six reserve managers (6.8%) disagreed about the benefits of the emerging technology.

“AI has only started, and its potential is large. It will become a normal tool for all reserve managers,” said an official from a high income central bank in Europe.

Which areas do you think will benefit most from this technology? (Please tick all that apply.)

Among the 82 reserve managers that said reserve managers’ operations will benefit from AI, reporting came out as the top area (70, or 85.4%). Trading and execution (58, or 70.7%), risk management (55, or 67.1%) and portfolio management (54, or 65.9%) are also areas in which central banks said AI can improve their operations.

“With the advent of artificial intelligence, portfolio management can be enhanced with data-driven insights and automation. AI can identify optimal asset allocation, rebalancing strategies, risk-adjusted returns, and tax efficiency for each portfolio,” said an official from an upper-middle income central bank in Africa. In their view, AI can also execute trades, monitor portfolios, adjust asset weights and generate reports “automatically and efficiently”.

They added: “AI can equally help to reduce portfolio risks, as it can help discover correlations between different assets, sectors or regions, and suggest optimal diversification strategies.”

Over half of reserve managers said strategic asset allocation (48, 58.5%) and cyber security (44, 53.7%) have potential AI applications. “I think macroeconomic projections and forecasting will also benefit from deploying AI in central banking,” said an official from an upper-middle income central bank in Europe.

A reserve manager from a high income European central bank explained how they are already using AI: “We have an internal solution that is able to analyse a significant volume of news and research.” They extract information on topics deemed most important, “as well as the sentiment related to them and for various asset classes”.

An official from another high income European central bank warned, however, that although “AI could improve data management”, such processes are also connected to significant cyber security, data mismanagement and operational risks.

Another official from a high income central bank in Europe said although they believe AI/machine learning can be useful to support their reserve management operations, “it will not replace the need for decision-making by the experts in the foreseeable future”.

Does your central bank incorporate an element of socially responsible investing (SRI) into reserve management?

Reserve managers were split on whether they incorporate socially responsible investing into reserve management. Forty-five out of 89 respondents to this question said they do (50.6%).

Sustainable responsible investing integration in reserve management begins with the central bank’s strategy, an official from an upper-middle income central bank in Europe said. Theirs stipulates “that one of [its] strategic objectives is increasing awareness of climate change” and contributing to a green sustainable economy.

Advanced economies are much more likely to incorporate SRI into their investments than those in emerging and developing economies. Of 28 advanced economy central banks, 23 (82.1%) said they incorporate SRI into reserve management.

In contrast, 22 out of 61 (36.1%) central banks in emerging and developing economies that addressed this question said they incorporate SRI in reserve management. Among emerging and developing economy central banks, 27 (44.3%) said they are considering incorporating SRI, and 12 (19.7%) said they are not.

Among the 15 central banks globally that said they are not considering incorporating SRI into reserve management, six are in the Americas, three in Europe, three in the Asia-Pacific, two in the Middle East and one is in Africa.

“Our central bank actively incorporates socially responsible investing into our reserve management strategy,” said a reserve manager from a lower-middle income central bank in Africa. “Our investment guidelines prioritise security, liquidity, yield and sustainability in that order. Sustainability is paramount, guiding us to favour investments of a responsible nature (ESG) when the first three principles are met.”

If “Yes”, does it include the following? (Please tick all that apply.)

Carbon footprint measurement is the most common way in which SRI is incorporated into reserve management (25 respondents, or 56.8%). Among the 44 reserve managers that answered this question, 20 (45.5%) said they do this in ‘Other’ ways. Publishing ESG principles (16, or 36.4%) and mandatory reporting (13, or 29.5%) were less common. Respondents could select as many options as they saw fit. Some selected all of them, while others did not pick any.

An official from a high income central bank in Europe said that it “was one of the first central banks worldwide to set up a dedicated green bond portfolio”. Last year, management at the central bank decided to double the size of this portfolio. “In the past years, we have published a TCFD [Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures] report, as well.”

A reserve manager from an upper-middle income central bank in the Americas said it internally reports “ESG risks [that] the foreign reserves are exposed to”, as “recommended by the TCFD and NGFS [Network for Greening the Financial System], as well as the impact in terms of carbon emissions”. The “first public reporting on these measures is planned to be within the central bank’s annual report for 2023.”

If “Yes”, how do you integrate SRI into your investment process?

Most reserve managers that incorporate SRI investment principles do so as part of their SAA. Of the 45 central banks that said they incorporate SRI into their investment process, 32 (71.1%) use this approach. Fewer, 17 (37.8%), implement standalone portfolio mandates. Participants could select one option, both or none.

Which strategies do you employ? (Please tick all that apply.)

Overall, among the 45 central banks that incorporate SRI into reserve management, investment in ESG bonds (32, or 71.1%) is the most popular strategy. ESG integration (22, or 48.9%) and negative screening (20, or 44.4%) are also common.

What percentage of your FX reserves portfolio do you consider SRI?

Most central banks of the 33 that said they integrate SRI into their reserve management and that answered this part of the question consider between 1–10% of their reserves SRI (22, or 66.7%). Just six central banks (18.2%) said they consider more than half of their FX portfolio to be SRI.

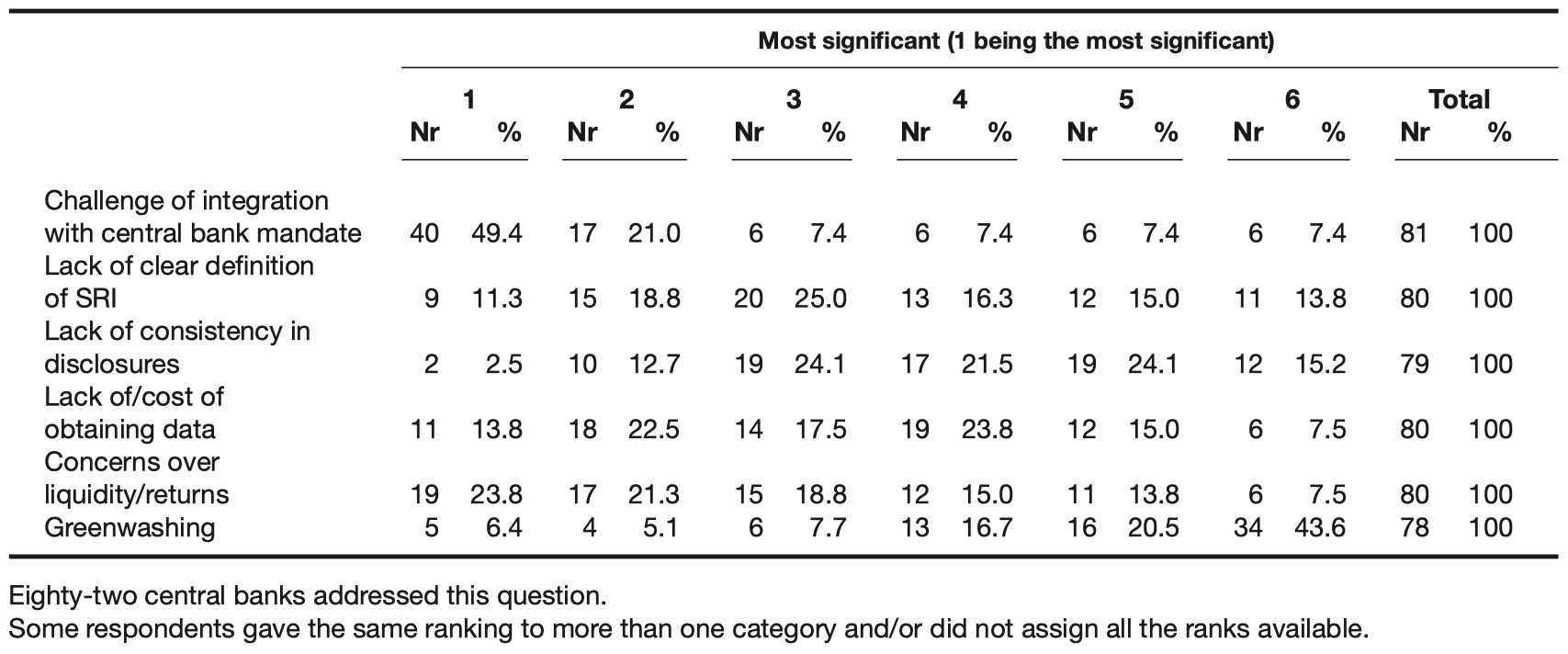

Which in your view are the most significant obstacles to incorporating SRI into reserve management? (Please rank the following 1–6, with 1 being most significant.)

A majority of central banks identify integration with the central bank’s mandate as the main obstacle to incorporating SRI into reserve management. Out of the institutions that ranked six hurdles to SRI adoption, 40 (49.4%) said this lack of alignment is the most significant. Adding first, second and third ranks together, concerns over liquidity and returns were the next most significant obstacle, followed by lack of a clear definition of SRI – although lack and cost of obtaining data followed closely behind.

However, there is also resistance to SRI among reserve managers themselves. An official from a high income jurisdiction in Europe said this is an area where “many central banks undermine the competitiveness of their own country” by purchasing foreign green bonds.

“To the central bank of a small and poor country that is facing so many challenges”, such as “very high inflation, exchange rate volatility, political instability”, SRI is “not on the list of priorities”, said a reserve manager from a lower-middle income central bank in the Americas.

Which view best describes your attitude to the following currencies?

Beyond the core reserve currencies, including the US dollar, euro, sterling and yen, a group of mid-sized western economies, or allies of the West, continue to receive investments from a wide set of central banks. This is the case for Australian, Canadian and New Zealand dollars, the Danish krone, Swedish krona, Norwegian krone, South Korean won and Singapore dollar.

Eighty-six central banks gave their view of the Australian dollar, and 46 (53.5%) said they are investing in it, compared with 41 (51.9%) last year. Similarly, 42 central banks (48.8%) this year said that they are investing in the Canadian dollar, compared with 38 out of 78 central banks (48.7%) in 2023.

In the case of the New Zealand dollar, 24 out of 84 central banks (28.6%) said they invest in the currency, compared with 23 out of 76 (30.3%) last year. The won and the Singapore dollar receive lower levels of interest, but they also remain relevant.

Eighty-one reserve managers answered on the South Korean won. Overall, 17 (21.0%) central banks invest in it, compared with 15 (20.0%) out of 75 respondents last year. In the case of the Singapore dollar, 20 out of 84 central banks that responded to this part of the question (23.8%) said they invest in it. In 2023, 16 out of 76 respondents (21.1%) said they were investing in the Singapore dollar.

The Swedish krona also holds a similar level of interest. Overall, 82 central banks assessed the currency. Among them, 17 (20.7%) said they are investing in it, compared with 18 out of 76 respondents (23.7%) last year.

The Canadian dollar, Swedish krona and onshore renminbi investments emerged as the currencies that the most central banks are considering investing in now, followed by the Australian dollar and Danish krone.

A slightly higher proportion of central banks reported making onshore investments in renminbi when compared with last year. This year, 47 out of 84 central banks (56.0%) said they are investing in mainland China, compared with 39 out of 76 (51.3%) in 2023.

Which best describes your attitude to the following asset classes?

Supranationals (94.3%), deposits with central banks and the official sector (92.0%), and government bonds with an above-BBB credit rating (91.0%) continue to be the undisputed leaders in terms of asset classes central banks invest in. Many central banks also continue to invest in deposits with commercial banks (76.7%), gold (74.1%) and US agency bonds (70.2%).

In terms of digital assets and currencies, although no central banks are considering investing in them now, a small group of reserve managers (13, or 15.9%) that answered for this asset class said they would consider investing in 5–10 years.

Just 14 out of 88 (15.9%) central banks said they have no interest in investing in green bonds, with the majority of reserve managers either already investing in them (49, or 55.7%) or considering allocating reserves in the asset class (11, or 12.5%). Around one-fifth, 16 out of 86 central banks (18.6%), said they have no interest in investing in social and sustainability bonds.

Interest in inflation-linked bonds has also remained stable year on year. Last year, 33 (43.4%) central banks said they were investing in inflation-linked bonds, and 13 (17.1%) said they were considering making an investment imminently. This year, 39 (44.8%) said they hold inflation-linked bond investments, and 10 (11.5%) central banks said they are currently considering making an investment.

Which of the following best describes your attitude to exchange-traded funds (ETFs)?

Around one-quarter of central banks (23, or 26.7%) out of 86 that addressed this question said they are investing in ETFs now. Eight (9.3%) said they are currently considering doing so, and 16 (18.6%) central banks said they may consider investing in 5–10 years. Many central banks said they have no interest in investing in ETFs (39, 45.3%).

If investing in ETFs, please say which underlying asset classes they give exposure to. (Please tick all that apply.)

Equities (chosen by 18, or 78.3%, of respondents) and credit (10, or 43.5%) are the most common ETFs that reserve managers from 23 central banks said they invest in. This year, gold and emerging-market ETFs were also included as options. Two central banks (8.7%) said they invest in gold ETFs, and four central banks (17.4%) said they use ETFs to gain exposure to emerging markets.

A reserve manager from a high income central bank in Europe said: “For us, ETFs are a cost-efficient way to obtain broad exposure to equities and credit.”

An official from a high income central bank in Europe said that “exchange-traded funds allow for broad, diversified exposure” to equity markets without operational challenges typical of direct investment, such as trading and settlement, accounting and taxation.

A reserve manager from a high income central bank in the Asia-Pacific said they use ETFs “for portfolio diversification, and tactical exposure” to over- or underweight certain regions, countries and sectors “on the basis of short-term views”. ETFs also provide them with “accessibility and cost-efficiency in terms of taxation, as compared to direct equity investing”.

“We have used ETFs to obtain access to assets that require a higher level of knowledge or technology than what we have,” said an official from an upper-middle income central bank in the Americas. They have “also considered ETFs to get exposure to ESG-linked assets”.

“We are assessing the use of ETFs as a way to introduce flexibility in our ESG portfolio management,” said a reserve manager from a high income jurisdiction in Europe that is part of the eurozone.

Does your central bank engage in repo and/or agency securities lending? (Please tick all that apply.)

Out of 90 central banks, 50 (55.6%) said they conduct repo or reverse repo activities that are managed internally, and 48 (55.3%) said they engage in securities lending via an agent. Twenty-one central banks (23.3%) said they do not engage in either.

An official from a lower-middle income central bank in Africa that engages in both said: “This multi-faceted approach enables us to leverage internal capabilities for repo transactions and benefit from external agents in securities lending.” They added: “Importantly, securities lending serves as a valuable tool, allowing us to generate additional revenue while contributing to the efficient functioning of financial markets.”

An official from a eurozone central bank said: “We often repo out our Treasuries which are trading special vs GC [general collateral]. We can also do reverse repo – however, rates are not yet attractive enough to do so.” An upper-middle income central bank in Africa has engaged in third-party agency lending, bilateral lending of its US Treasuries and repo/reverse repo transactions. However, “all collateral management is conducted internally”, the reserves manager said.

An upper-middle income central bank in the Americas is “considering securities lending via an agent”. Repos have just been approved, and are set for operationalisation this year, an official from a low income central bank in Africa said.

What are your main considerations for agency securities lending? (Please tick all that apply.)

The overwhelming majority of central banks that engage in securities lending said that the credit quality of collateral is their main consideration (44 out 45 respondents, or 97.8%).

“Apart from the difficulty of finding a fair split, liquidity is a big issue,” said an official from a high income central bank in Europe. Securities lending can deliver extra returns “without hard work”, “but nobody knows how long the chain of loans is, and therefore it is hard to evaluate the liquidity risk”.

They also said that borrowing banks certainly “use securities lending for covering certain regulatory requirements”, but “regulation is so complicated” that it is impossible to evaluate “all scenarios under which securities lending can turn into a trap”.

“It is also important for us to assess the agent’s ability to reinvest the cash collateral, as this is also a key part of our securities lending programme,” said an official from an upper-middle income central bank in Africa.

Who do you utilise as your agency securities lending agent?

Most central banks that engage in securities lending use their global custodian as their agency securities lending agent (39 out 45 central banks, or 86.7%).

An official from a lower-middle income central bank in Africa said: “By utilising our global custodian as our agency securities lending agent, we streamline operational processes and benefit from a consolidated and integrated approach.”

However, an official from an upper-middle institution in Africa said the central bank chose a third-party agency lender for reasons of double indemnity and “a more attractive revenue-sharing arrangement than a global custodian”.

A high income European central bank official said: “We use our global custodian for automatic securities lending (intraday). A third-party agency lender is used for traditional securities lending activities.”

With respect to liquidity management, which products do you use? (Please tick all that apply.)

The majority of central banks (80, or 89.9%) use deposits with central banks and official institutions for liquidity management. The next most commonly used products are T-Bills and short-term government securities (75, or 84.3%), followed by deposits at commercial banks (62, or 69.7%).

What percentage of your portfolio is less than six months in duration?

There is considerable variation between the shares of central banks’ reserves portfolios that are less than six months in duration. Sixty-nine institutions answered this question. Among them, the range was 0–100%, and the average share of reserves less than six months was 34.6%.

Two central banks (2.9%) said no part of their reserves portfolio is less than six months in duration. Ten central banks (14.5%) said that between 1–10% of their reserves portfolio is below six months in duration, and 17 (24.6%) said between 11–25% of their reserves portfolio is. Central banks are most likely to have 26–50% of their reserves portfolio with a duration of less than half a year (25, or 36.2%). Fifteen central banks (21.7%) said that between 51–100% of their reserves portfolio is less than six months in duration.

Do you use derivatives in your reserve management?

Globally, two-thirds of central banks said they use derivatives in reserve management.

If “Yes”, which derivatives do you use? (Please tick all that apply.)

By far the most common derivatives that central banks use in their reserve management are FX swaps (48, or 81.4%), followed by bond and rate futures (45, or 76.3%). Other derivatives used include FX forwards and inflation swaps.

If you use derivatives, please say for what purpose(s). (Please tick all that apply.)

Most central banks use derivatives for hedging purposes – 52 out of 59 central banks (88.1%) that use derivatives and answered the question limit risk in this way.

“Hedging is employed to mitigate market risks and enhance portfolio resilience. Duration management involves using derivatives to align interest rate sensitivity with our broader investment strategy,” said a reserve manager from a lower-middle income central bank in Africa. “Additionally, we utilise derivatives for yield enhancement, optimising returns while maintaining a prudent risk profile.”

“Gold derivatives may be used in the future for active management of the gold position,” said a reserve manager in an upper-middle income central bank in the Americas.

Do you use central clearing for OTC derivatives?

Around one-fifth of the 49 central banks that use derivatives and answered this question said they use central clearing (11, or 22.4%). Five (10.2%) are considering this option. Most central banks (33, or 67.3%) said they do not use central clearing for over-the-counter derivatives.

“For FX swaps, these are done bilaterally, and we do not use central clearing. Meanwhile, futures are traded on exchange,” said an official from a eurozone central bank. “We are planning to introduce euro OIS [overnight indexed swap] in 2024,” said an official from a central bank that is also a high income eurozone institution. “Since we are already a direct clearing member at Eurex, we will extend our repo licence to IRS [interest rate swap] clearing.”

An official from a high income central bank in the Asia-Pacific said: “Most FX swaps are settled through CLS [continuous linked settlement].”

“We have a project in the pipeline to move to centrally cleared OTC derivatives,” said an official from a third high income eurozone central bank.

What percentage of your FX reserves is in equities?

The majority of central banks continue to report low equity allocations. Among the 87 institutions that addressed the question this year, 62 (71.3%) respondents said they invest none of their reserves in this asset, and two said they invest less than 1%.

Nonetheless, 14 (16.1%) participants invest between 1–10% of their reserves in equities, six central banks (6.9%) invest between 11–25%, and three (3.4%) invest between 26–50%. A total of 25 central banks out of 87 that answered the question (28.7%) invest in equities.

Among the nine central banks managing less than $1 billion in reserves, just one said it invests in equities. Of the 34 central banks that manage $1–10 billion, 11 said they invest in equities.

Just three of the 11 central banks that manage between $11–25 billion invest in equities, and just two of the 10 central banks with between $26–50 billion in reserves do.

One of the seven central banks managing $51–100 billion said they invest in equities, and seven of the 16 central banks with a reserve holding of over $100 billion invest in equities.

Are you considering a change in the next 12 months?

Six central banks are considering increasing their investments in equities in the next 12 months. Two are in the eurozone, two are in Europe but do not use the euro as their national currency, one is in the Asia-Pacific region, and one is in the Americas.

A reserve manager from one of the central banks in Europe planning to increase its investment in equity said: “Despite pretty high standalone volatility, equities act as diversifiers, reducing overall investment portfolio risk. Over the long-term horizon they considerably enhance investment return.”

Three central banks are considering investing for the first time. Two of the central banks considering investing for the first time are in Europe – one of which is in the eurozone – and the third is in the Americas.

How do you invest in equities? (Please tick all that apply.)

Central banks that invest in equities tend to use passive strategies (12, or 48.0%), ETFs (12, or 48.0%) and external mandates (11, or 44.0%).

“The equity sleeve of our reserves portfolio is managed externally mostly due to capacity. Also, this is done to benefit from the expertise and specialised knowledge of managers in the field,” said a reserve manager from an upper-middle income central bank in Africa. “Having said that, our external managers are obliged to adhere to strict investment guidelines and regularly report on their performance.”

“We are looking to progressively move away from investing in funds to giving Paris-aligned mandates to managers,” said one reserve manager from a eurozone central bank.

“We used external managers, but then found that, for a passive strategy, internal management is capable, as well. Therefore, after more than a decade, all equity portfolios are under internal management,” said an official from a high income European central bank.

Do you manage your gold reserves actively?

Most respondent central banks (55, or 70.5%) do not actively manage their gold reserves. Of 78 central banks that answered this question, 23 (29.5%) said they do.

If “No”, why? (Please tick all that apply.)

Among 52 respondents to the question as to why the central bank does not actively manage its gold reserves, the most common reason was central bank policy (29, or 55.8%).

“We do not hold gold reserves,” said a reserve manager from an upper-middle income central bank in the Asia-Pacific. Central banks that stated they do not hold gold in their reserves were not included in the analysis.

If “Yes”, which products do you use? (Please tick all that apply.)

Twenty-two central banks addressed the question as to which products they use to actively manage their gold reserves. Most central banks use deposits (14, or 63.6%), swaps (9, or 40.9%) and spot trading (9, or 40.9%).

“Gold is mostly held as a strategic asset, and, as such, is not traded actively. However, to generate income on our gold holdings, we make gold deposits with counterparties with strict eligibility,” said a reserve manager from an upper-middle income central bank in Africa. “For more investment flexibility, we also swap part of our gold (against USD) with the view of reinvesting the USD in higher-yielding albeit safe assets (eg, UST).”

“We use gold/FX swaps to enhance return from time to time depending on [the] market situation. The underlying gold allocation, however, remains static,” said a reserve manager from a eurozone central bank.

“In the past [few] years, we have tried to maintain our physical allocation to gold constant, while adjusting our exposure through options and futures,” said a reserve manager from an upper-middle income central bank in the Americas.

A reserve manager in a lower-middle income central bank in Africa said that, although their “gold is held locally”, they “are considering active investment in gold through swaps and deposits”.

“We don’t manage gold actively recently because of the rates,” a reserve manager from an upper-middle income central bank in Europe said. But when they do, they “invest in gold deposits”.

“We might consider actively managing in the future through swaps, deposits, ETFs, options or futures,” said a reserve manager from an upper-middle income central bank in the Americas. Another reserve manager from a eurozone central bank said: “We would use deposits if we decide[d] to manage our gold actively. In the future, we plan to implement gold swaps.”

Over the last year, have you changed your view on the euro as a reserve currency?

Last year, higher interest rates in the eurozone increased the euro’s attractiveness as a reserve currency. This year, of 67 central banks that responded to this question, 41 (61.2%) said they think the euro has become more appealing. In contrast, 26 central banks (38.8%) said the euro has become less attractive.

In 2023, 62 out of 71 respondents (87.3%) said the euro had become a more attractive currency, and nine (12.7%) said it had become less attractive.

Removing eurozone central banks from the analysis, out of 59 respondents to this question, 36 (61.0%) said the euro is a more attractive currency. Among eight eurozone central banks that answered this question, five (62.5%) said it is a more attractive currency.

If investing in the euro, please give the share of your portfolio invested.

Globally, respondents are most likely to invest 1–10% of their reserves in the euro (22, or 33.8%).

Removing eurozone central banks from the analysis left 57 respondents to this question. Ten non-eurozone central banks said they are investing less than 1% of their reserves in the euro. Twenty-two said they are investing between 1–10%. Eight said they are investing between 11–25% of their reserves in the euro. Six are investing between 26–50%, and 11 between 51–100%. Two of the central banks investing between 51–100% are outside Europe.

Do you plan to increase euro investments in 2024?

Of the 18 central banks that said they are planning to increase their investments in the euro in 2024, three are in the eurozone, two are in Europe but not in the eurozone, five are in the Asia-Pacific region, two are in Africa, and one is in the Middle East.

“We are thinking about re-establishing our euro portfolio, which we had closed [at] the beginning of 2021,” said a reserve manager from a eurozone central bank.

“We had invested in euros in the past, but stopped doing so when rates were negative,” said a reserve manager from a lower-middle income central bank in the Americas. “Now that rates are back to positive levels, we are reconsidering.”

One reserve manager from another eurozone central bank said: “Since the euro area has positive rates again, the euro has become more interesting.” The central bank has increased its euro investments from cash into bonds, and will continue to do so in 2024. The official added that the central bank has also seen increased investment from their reserve management clients.

In contrast, another eurozone central bank does not view investing in the euro as a profitable option: “Given [that] we are part of the Eurosystem, the decision to invest in euro-denominated assets is primarily a decision based on expected return. We currently expect this return to be negative once funding costs have been considered.”

A reserve manager from an upper-middle income African central bank said that, although since leaving negative interest territory, the “attractiveness of the euro as a reserve currency has increased”, in their view, it is relatively less attractive against the US dollar because of economic challenges within the eurozone, the changing global economic landscape and the interest rate differential. They added that there are also “more opportunities to diversify reserve currency preferences with the rise of emerging economies, such as India”.

“We think that [the] diversification benefits of investing in euro[s] are offset by exchange rate volatility,” agreed an official from an upper-middle income central bank in the Americas.

An official from an upper-middle income central bank in Europe said: “We will increase the euro as a share of our reserves taking into account its increased weight in our country’s trade balance and the euro-integration our country is going through.”

An official from a lower-middle income central bank in Africa said: “We will continue to monitor its performance in 2024 for future consideration.”

What is the main hurdle for your institution to start investing in euro-denominated assets or increase current allocations? (Please tick all that apply.)

Of the 62 central banks that answered regarding their main hurdle to investing in the euro, most pointed to weak growth prospects (28, or 45.2%). Fifteen central banks (24.2%) cited a lack of supply of AAA assets, and the same number stated their low trade with the eurozone was the main hurdle.

“Low yields and inverted yield curves” in creditworthy European countries are a barrier to investment, an official from a eurozone central bank said. A reserve manager from an upper-middle income central bank in Africa said “the yield differential between the UST and its European counterparts” as well as the dollar’s “persistent” strength rendered “US sovereigns as more attractive”.

“Interest rate differential vs USD and FX volatility” are hurdles to investment in the euro, said one reserve manager from a high income jurisdiction in the Americas. “Foreign exchange fluctuation could result in significant losses,” agreed a reserve manager from an upper-middle income jurisdiction in the Americas.

A reserve manager from a high income central bank in the Asia-Pacific said the euro has “less liquidity compared to the US”. An official from an upper-middle income central bank in the same region said they see “low returns and risk of FX volatility” as barriers to euro investment.

An official from an upper-middle income central bank in the Americas said their main hurdle “is related to operating issues” that affect their capacity to “effectively invest in euro-denominated assets”. A reserve manager from a lower-middle income central bank in the Asia-Pacific said the “low level” of their reserves is prohibitive to investment in the euro.

The “Eurosystem has so many EU bonds”, through different asset purchase programmes, that there is “not much room” to add more euro investments, an official from a eurozone central bank said.

“We foresee a weaker risk-return profile” of the euro, said an official from a high income central bank in the Americas.

An official from a lower-middle income central bank in the Asia-Pacific said: “Our main trading partners deal in the dollar.”

If investing in the renminbi, please give the share of your portfolio invested.

A majority of central banks investing in the renminbi allocate 1–3% of their total reserves to this currency. Overall, 47 reserve managers provided an answer to this question, and 31 (66.0%) of them said their allocations are within that range. Respondents that answered zero were not included in the analysis.

Among the central bank respondents investing in renminbi, eight are in the eurozone, seven are in Europe, 12 are in the Asia-Pacific region, eight are in the Americas, 10 are in Africa, and two are in the Middle East. In this group, 18 central banks are in high-income jurisdictions, 14 are in upper-middle, 12 are lower-middle and three are in low-income countries.

What percentage of global reserves do you think will be invested in the renminbi by:

Most reserve managers think that the renminbi’s share of global reserves will continue to rise throughout the decade. While no central banks expect the renminbi’s share to reach 10% or higher by the end of 2024, six central banks (10.2% of 59 respondents) expect it may do so by 2030.

By 2035, 22 central banks expect the renminbi’s share of global reserves to reach 10% or more, of which five central banks said they expect the renminbi’s share of global reserves to exceed 15%.

Respondents for the most part expect renminbi reserves to remain between 1–3% by the end of this year (42, or 71.2%). This falls dramatically to 20.3% of respondents expecting renminbi in global reserves to remain at this level by 2030, and falls to just 8.5% by 2035.

Nevertheless, the renminbi’s share of global reserves is still expected to remain between 4–12% at the end of 2035, according to 81.4% of respondents (48).

“[The] weight of renminbi in global reserves has been increasing for quite a long time now,” said a reserve manager from an upper-middle income central bank in the Americas. “As the Chinese economy continues to grow and influence global markets, it is conceivable that central banks will also gradually adapt their allocations to reflect the importance of the most relevant economies, including the Chinese economy.”

However, a reserve manager from an upper-middle income African central bank points out that, “despite China’s efforts to internationalise its currency, there have been several challenges that have hindered its progress in becoming a widely accepted reserve currency”. In their view, “some remaining concerns are the lack of convertibility and liquidity of the yuan in global markets”. Also, “the utilisation of the yuan in cross-border transactions has been mostly limited to countries viewed as being ‘antagonistic’ to the western financial ecosystem”.

Indeed, an official from a eurozone central bank said they think the renminbi’s share of global reserves “will decrease because of geopolitical tensions”. The official from the upper-middle income African central bank added that the “negative interest rate differential, [as well as] monetary policy divergences between China and the US” have also made renminbi assets less attractive.

“While renminbi is a good diversifier against traditional reserve assets”, China’s weaker growth prospects and “the reconfiguring of global supply chains could make investors cautious about increasing their exposure”, an official from an upper-middle income central bank in the Americas said.

However, an official from an upper-middle income central bank in the Middle East said that, although recently investors have been decreasing their RMB holdings “due to the fear of sanctions” because “China supports Russia in the war”, as well as “financial market risks and declining growth prospects in China”, they believe that in the long run the share of renminbi in global reserves will continue to increase. However, they also said that, “based on the recent outlook”, they downsized their estimates.

“We think that the share of renminbi will have a slight increase, thanks to de-dollarisation,” a reserve manager from a eurozone central bank said, but added that “we also believe that lack of transparency and geopolitical conflicts are the main hurdles to seeing a greater shift in the future”.

Also seeing factors that can drive and hinder the renminbi’s adoption in reserves, an official from an upper-middle income European central bank said progress in the liberalisation of the Chinese financial markets and the inclusion of Chinese bonds in major global bond benchmarks might support the renminbi, but the process may be slow due to “geopolitical tensions with [the] US and Taiwan, capital controls” and a “lack of full exchange rate flexibility”.

What percentage of your reserves do you plan to invest in renminbi by:

Of the 11 central banks that expect their own exposure to renminbi to reach or surpass 10% by 2035, four are in the Asia-Pacific, four in Africa and three in the Americas. Five are in lower-middle income jurisdictions, three in upper-middle, two in low income and one is in a high income country.

“We have trimmed down our allocation to renminbi due to the yield differential between UST and its Chinese counterparts, as well as persistent dollar strength,” said an official from an upper-middle income African central bank. They are “also wary of China’s credit outlook, especially with the ongoing downsizing of the property sector and continued impact on growth, which has remained persistently lower in the medium term”. Over the long term, as global interest rates and global growth normalise, they said they “may consider” increasing their exposure to Chinese government bonds.

An official from an upper-middle income central bank in the Americas said: “While there is scope for significant diversification from exposure to renminbi, geopolitical risks related to China have gained considerable traction over the past four years, and will continue for the foreseeable future and thus discourage investment for the moment.”

“Given the negative prospects of the Chinese economy, we expect the renminbi to underperform this year, and hence we do not plan additional investments,” said an official from a high income European central bank.

A reserve manager from an upper-middle income country in the Middle East said the central bank holds renminbi “for diversification purposes”, as well as a consequence of swap lines with China. However, the central bank’s currency allocation is mainly determined by an asset-liability matching principle during its SAA decision-making process. Therefore, the central bank anticipates that the share of renminbi in its reserves “will stay limited” unless there is a significant increase in the swap lines with China.

A reserve manager from a low income central bank in Africa said its “expectation is to increase investments due to trade with China”.

Note

1. Percentages in tables may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: subscriptions.centralbanking.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com test test test

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com test test test