NDF interventions in Latin America

Elisa Vilorio Painter

Executive summary

Trends in reserve management: 2023 survey results

The role of gold in central bank reserves

Will the dollar remain the world’s reserve currency?

Interview: Golan Benita

Reserve management at the BCB

NDF interventions in Latin America

Appendix 1: Survey questionnaire

Appendix 2: Survey responses and comments

Appendix 3: Reserve statistics

Were Latin American central banks successful in their use of non-deliverable forwards as a key FX intervention tool?

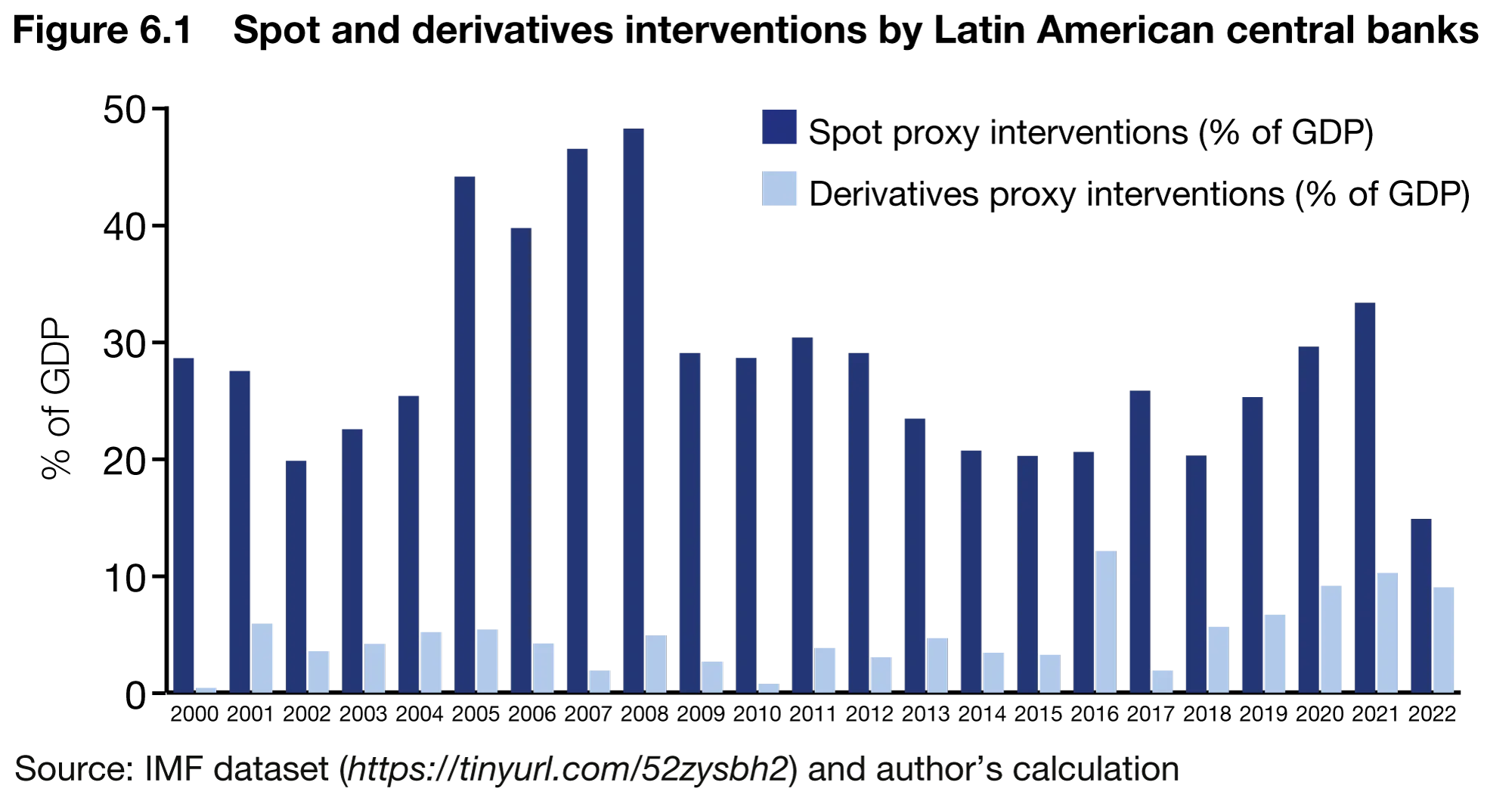

While foreign exchange (FX) spot trading activities remain the dominant intervention tool in the FX markets for most central banks in Latin America, the use of FX derivatives as an FX policy tool has increased over time. Figure 6.1 shows yearly cumulative interventions in the spot and derivatives markets as a percentage of GDP for a selected sample of Latin American central banks, namely: Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Chile, Ecuador, Mexico, Paraguay and Peru. Using figures from the IMF dataset for Foreign Exchange Interventions (FXI) from 2000 to August 2022, the data highlights the increasing role of FX derivatives as a percentage of GDP. By the end of August of 2022, the total weighted average use of derivatives by the pool of countries reached 8.96% of their GDPs, compared with 1.86% in 2017 – representing an increase of 382% during the past five years.

Within the FX derivatives instruments, the role of non-deliverable forwards (NDFs) has increased significantly during the past decade. An NDF is a foreign exchange contract to buy or sell a specific currency on a future date for a fixed price set on the date of the contract. At maturity, on the settlement date, if the prevailing spot market exchange rate is greater than the previously agreed forward exchange rate, the holder of the contract must pay the holder of the other side of the contract the difference between the contracted forward price and spot rate. The contract is net-settled in US dollars or domestic currency, depending on the terms of the agreement, based on the notional amount.

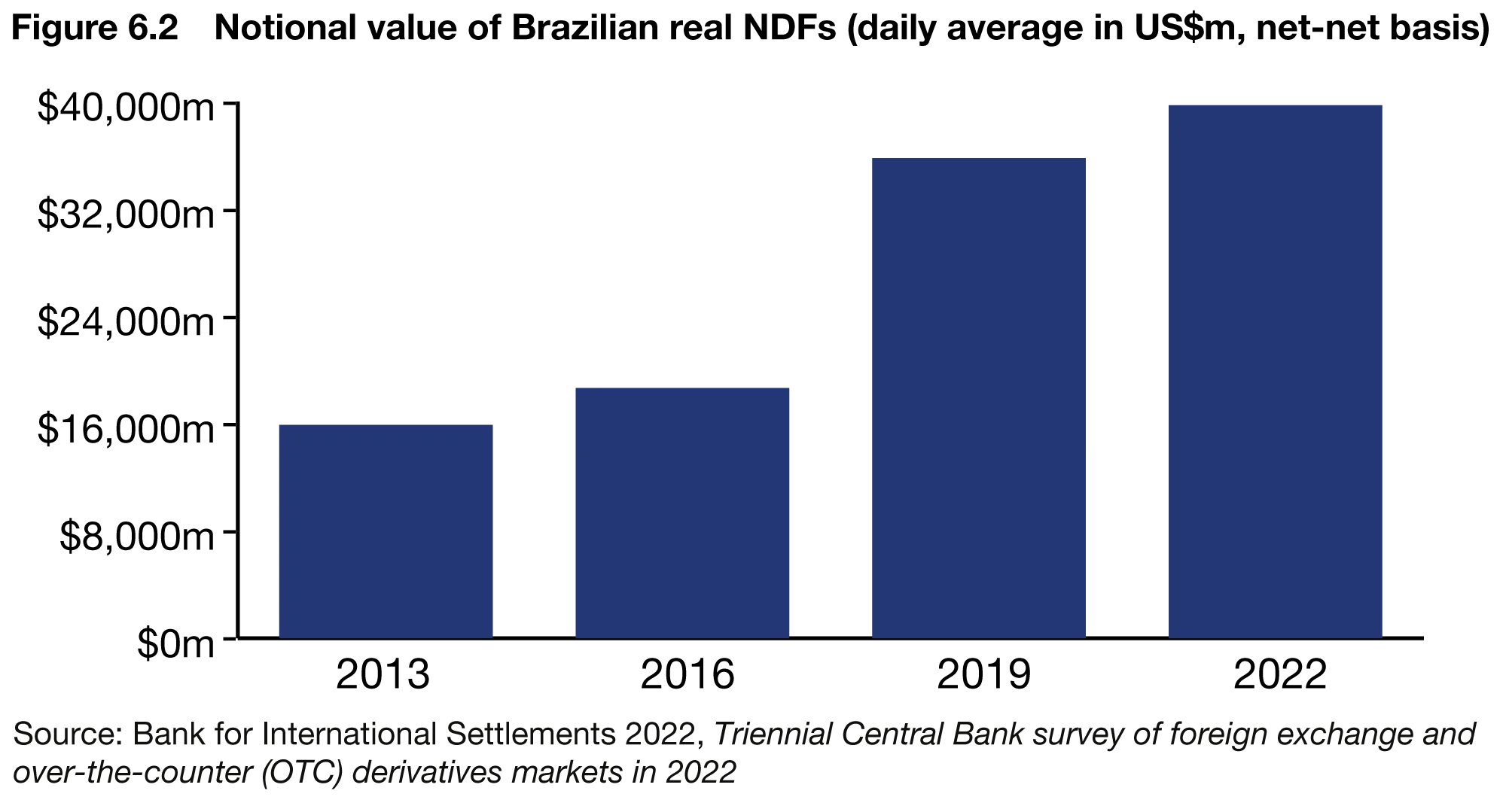

In Brazil (as shown in Figure 6.2), the trading of this type of derivative increased by 150% from 2013 to 2022, according to the Bank for International Settlements’ Triennial Central Bank survey of foreign exchange and over-the-counter (OTC) derivatives markets in 2022. The volume of Brazilian real NDF trading is partially attributed to the relative abundance of onshore currency products. Brazil has an active onshore futures market. Some offshore NDF traders that have gained access to this market also seek to capture the premium for NDFs versus onshore currency forwards and futures, if they believe the premium compensates them sufficiently for their exposures to convertibility and local counterparty risks.

Policy-makers are interested in the dynamics of the NDF market because they can be used to hedge exposures or speculate on a move in a currency where local market authorities limit such activity. Furthermore, NDF prices provide useful information for market monitoring as their prices reflect market expectations, as well as supply and demand dynamics that cannot be fully observed in onshore currency product prices in countries with capital controls. NDFs also provide important information for authorities to gauge market expectations of potential pressures on an exchange rate regime going forward. NDF prices can also be affected by the perceived probability of changes in the foreign exchange regime, speculative positioning, conditions in the local onshore interest rate market, and the relationship between the offshore and onshore currency forward markets. When international investors have little access to a country’s onshore interest rate market or deposits in local currency, NDF prices for that currency are primarily based on the expected future level of the spot exchange rate.

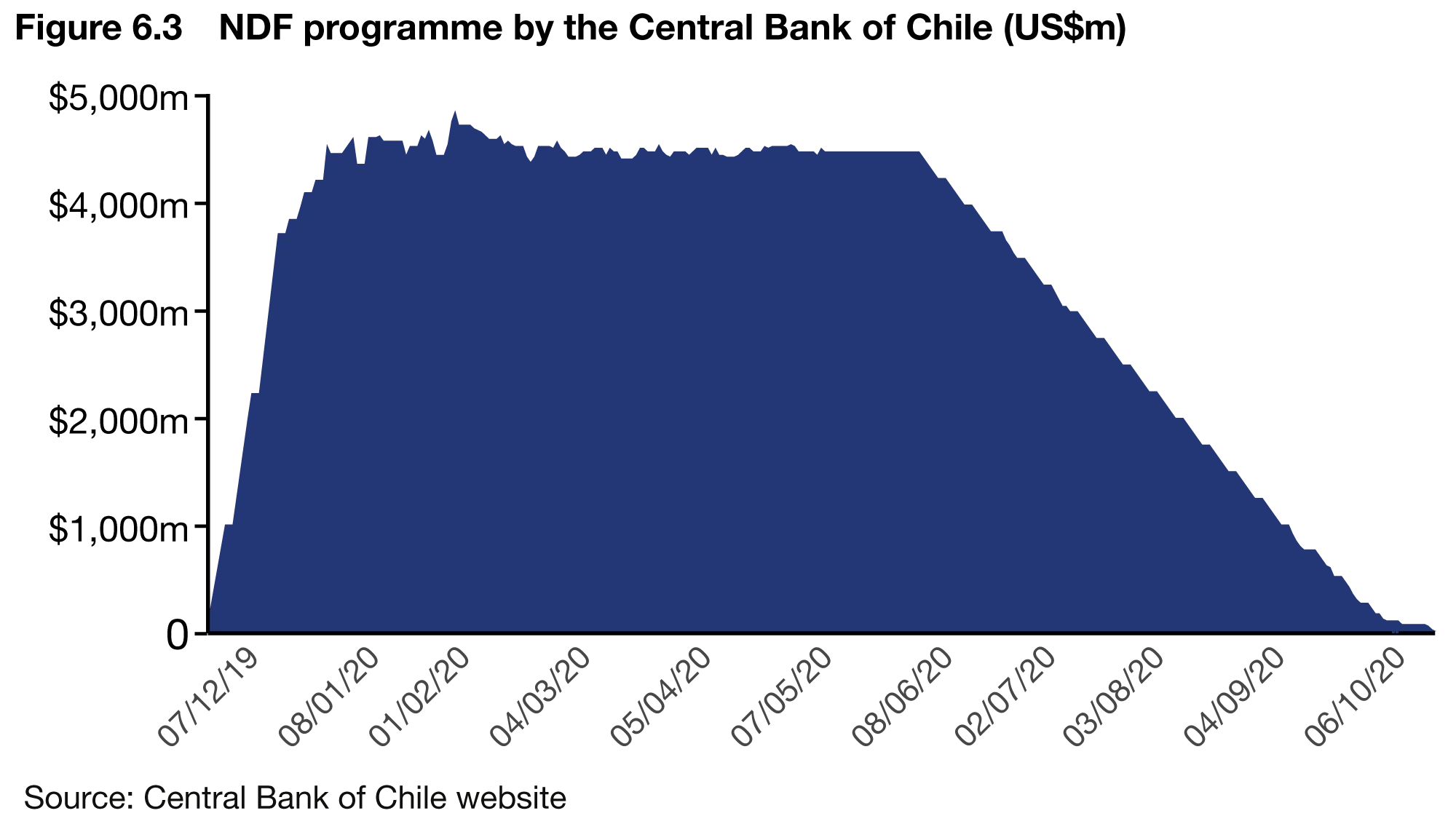

In contrast to spot FX interventions, NDF interventions are self-sterilising and do not require transfers of reserves. Central banks that use NDFs that settle in local currency do not directly use FX reserves. However, NDF interventions do have an impact on domestic liquidity, the magnitude of which depends on the type of contracts (notional or difference settlement, daily or monthly adjustment). This impact could be large and would have to be sterilised at a cost for the central bank. To this effect, the IMF recommends the NDF book should be capped for those central banks that sterilise liquidity injections via FX sales, or if the additional liquidity creation might feed into demand for FX. For example, this cap could be set on the contract amount equivalent to the reserves held in excess of the minimum adequate level at the 12-month horizon, factoring in drains from spot and outright forward intervention programmes. The Central Bank of Chile (as shown in Figure 6.3) capped and let mature its NDF programme as the FX market stabilised after the Covid-19 pandemic. These measures helped provide US dollar liquidity needed by some banks following outflows by non-residents and reduced the bank’s US dollar funding costs.

Another important factor in using NDF interventions to sell foreign (and buy local) currency besides those not limited by the supply of foreign reserves, is that a central bank must consider whether an NDF operation is likely to have the same effect on the exchange rate as the corresponding spot intervention. In other words, the central bank needs to examine the different effects on interest rates and capital flows when using NDFs versus spot market interventions.

Taking into consideration all the above, the objective of this chapter is to analyse if the use of NDFs by central banks in Latin America have proven to be successful.

Scorecard for LatAm NDF interventions

In the absence of a derivatives market, agents with exchange rate exposure must pre-finance FX domestic currency obligations with spot foreign exchange purchases or sales to avoid exchange rate risks. It follows that any impairment of an otherwise functioning derivatives market will transfer the demand for hedging to the spot market, and therefore have a destabilising effect. Therefore, forward market interventions rely on the transmission mechanism from forward to spot market rates, which is affected by money market conditions as well as exchange rate and capital controls.

The benefits of a functioning derivatives market to monetary policy and financial stability include agents’ resilience against exchange rate developments. Hence, the importance of derivatives markets could be measured relative to spot market turnover, domestic banks’ balance sheets and net open FX positions of various sectors of the economy.

In normal circumstances, central banks would only intervene in the derivatives market to manage the demand for hedges. They would not intervene in a functioning derivative market to address disruptions in the spot market, for example, when demand for cash is the issue. However, managing the demand for hedges would have positive spillovers in the spot market due to the interconnections between these markets. An exception to this rule is if the derivatives market is large and central to price discovery. Here, intervening in the derivatives market can be the most efficient and immediate way to support spot exchange rates.

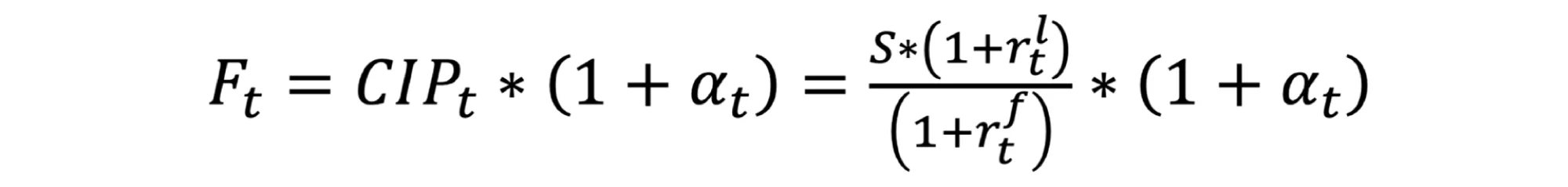

The key variable to monitor in NDFs is the cost of hedging measure as set out in the covered interest parity (CIP) premium. An increase in the cost of hedging could have a destabilising effect on derivatives and spot markets that could warrant intervention in the derivatives market. Following Du, Tepper and Verdelhan (2018),1 deviations between the forward rate (F) and CIP are represented by α, which reflects the demand for safe assets (US dollars), which increases in times of crisis, and balance sheet/supply constraints. S is the spot exchange rate; while rl represents the local interest rate and rf represents the foreign interest rate. This relationship is represented in the following equation:

Figure 6.4 shows the CIP premium for the one-month tenor during the Covid-19 pandemic for Mexico. The actual forward rate increased more than the theoretical value, pointing at an increase in the cost of hedging. Among the measures implemented by the Bank of Mexico during the pandemic was the use of NDFs, which helped stabilise the trend of peso depreciation.

When the Bank of Mexico initiated its NDF programme in 2017, the Mexican peso (MXN) was under severely stressed market trading conditions. In this environment, domestic non-bank financial institutions and non-financial corporations needed to hedge their exchange rate risk, but did not want to enter outright FX transactions (spot or forward). In response, the central bank introduced the FX hedging mechanism, offering NDFs denominated and settled in Mexican pesos to local banks through a system of interactive and competitive auctions at a variable price. The total initial programme envelope was $20 billion, but only $5.5 billion were allotted in the year it was initially implemented.

The NDF hedging programme was increased to $30 billion with the onset of the Covid-19 crisis. Beyond the signalling effect, the actual impact was small. Demand was less than $2 billion in two auctions at various maturities up to three months. This amount has been added to regular rollover auctions with a total amount outstanding of almost $7.5 billion at the end of September 2022. Therefore, NDFs should be seen as complementary to other settling FX spot intervention tools, as success may depend on showing both willingness and the ability to use the reserves.

Some academic research has shown that derivatives-based intervention can be effective. Kohlscheen and Andrade (2014)2 finds that the auction of Brazilian non-deliverable FX futures (a different way of describing NDFs) settled in local currency had a significant effect on intraday exchange rates. Chamon et al (2017),3 show that a programme of preannounced intervention using the same instruments was effective, although it did not affect exchange rate volatility. One important caveat related to these previous studies is that tests of intervention in either the spot or forward market tend to be subject to high endogeneity – it is often difficult to separate the effects of the circumstances that prompted the intervention (such as capital flight) from the effects of the intervention itself. Another approach to measure the effectiveness of NDF programmes is to compare the FX volatility before and after the intervention. The only caveat is the endogeneity of other confounding factors that cannot always be isolated as previously mentioned. Finally, one would be interested in analysing the profitability of intervention under the assumption that interventions to support FX market should be profitable in expectation (Friedman 1953; Sandri 2020).4

Furthermore, NDFs represent a useful tool to manage excess volatility in the bid-ask spread of the currency. In March 2020, the bid-ask spread of Colombian pesos/US dollars reached its highest value. To mitigate the pressure, the Central Bank of Colombia sold $1 billion of NDFs per month during March–May 2020. The advantages of the measure included that international reserves were not affected. In addition, the Central Bank of Colombia auctioned USD through NDFs and FX swaps to provide liquidity in the FX market. While providing liquidity and supporting local financial markets, the central bank increased its foreign liquidity buffers by accumulating nearly $5 billion in international reserves during 2020.

In conclusion, based on the empirical evidence discussed above by the sample of countries analysed in Latin America, the use of NDFs has been effective in smoothing trend movements in the exchange rate when price pressures dominate. Spot interventions are used in reaction to daily movements in the exchange rate and to address capital flow pressures. It should be noted that the applicability of best practices to measure the effectiveness of NDFs explained in this chapter depends on country-specific circumstances, including central bank credibility, the structure and depth of the foreign exchange market, and the macroeconomic and political environment. Given the empirical evidence, which suggests that interventions in derivatives markets can be no less effective than interventions in spot markets, it highlights the usefulness of NDFs to the broader central bank toolkit. Finally, a clear understanding of the objectives of the intervention in NDFs, underpinned by the appropriate communication consistent with other policies is key for a successful execution, which requires a sound understanding of the market microstructure in each country.

Notes

1. Du, W, Tepper, A, and A Verdelhan, ‘Deviations from covered interest rate parity’ in The Journal of Finance 73(3), February 2018, pages 915–957.

2. Kohlscheen, E and SC Andrade, ‘Official FX interventions through derivatives’ in Journal of International Money and Finance 47, October 2014, pages 202–216.

3. Chamon, M, Garcia, M and L Souza, ‘FX interventions in Brazil: a synthetic control approach’ in Journal of International Economics 108, September 2017, pages 157–168.

4. Friedman, M, Essays in positive economics (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1953); Sandri, D, 2020, FX intervention to stabilize or manipulate the exchange rate? Inference from profitability, IMF Working Paper WP/20/90, International Monetary Fund, June 2020.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.centralbanking.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com