Trends in reserve management: 2023 survey results

Executive summary

Trends in reserve management: 2023 survey results

The role of gold in central bank reserves

Will the dollar remain the world’s reserve currency?

Interview: Golan Benita

Reserve management at the BCB

NDF interventions in Latin America

Appendix 1: Survey questionnaire

Appendix 2: Survey responses and comments

Appendix 3: Reserve statistics

This chapter reports the results of a survey of reserve managers that was conducted by Central Banking Publications in February and March 2023. This survey, which is the 19th in the annual HSBC Reserve Management Trends series, was made possible by the support and co-operation of the reserve managers who take part in it. The reserve managers contributed on the condition that neither their names nor those of their central banks would be mentioned in this report.

Summary of key findings

-

Above-target inflation is the most pressing issue facing reserve managers in 2023. Overall, 55 central banks placed it as the main risk. These institutions represent 70.5% of the 78 central banks that addressed the question.

-

Geopolitical risk has become increasingly important. In total, 79 central banks assessed the importance this risk would have this year, and 13 (16.5%) say it is their main concern.

-

A majority of reserve managers reduced duration as a precautionary measure to protect their portfolios’ value over the last year. Nonetheless, due to the fact that central banks are increasing interest rates more than expected, the policy-sensitive two-year bond benchmark has also recorded significant yield increases. Partly as a result of it, 12 (15.4%) reserve managers say they increased duration in the last year.

-

Reserve managers are divided on volatility’s impact on asset diversification. Overall, 28 (35.9%) reserve managers say they expect the current market environment to foster an acceleration in asset diversification. The same number think there will not be changes in diversification, while 20 (25.6%), think the current environment will slow down the pace of diversification in 2023.

-

A majority of participants report low equity allocations. Among the 82 institutions that addressed the question, 58 (70.7%) respondents invest less than 1% of their reserves in this asset. In fact, 56 (68.3%) do not invest at all in this asset.

-

The main objective central banks pursue through their equity investments is to increase returns. In the group of 32 reserve managers that responded to this question, 20 (62.5%) selected this option.

-

Regarding risks facing sovereign bond markets, out of the 82 central banks that responded to this question, 39 (47.6%) selected the Fed’s QT as their top risk, and 14 (17.1%) highlighted lack of liquidity in the US Treasury market.

-

Although a large majority of reserve managers assess their portfolios are at adequate levels, a significant number of respondents say they intend to increase their resources over the coming year.

-

Most respondents think central banks will continue increasing their gold holdings in the coming year. In total, 76 central banks provided an answer to this question, 51 (67.1%) say that gold investments will increase.

-

Higher interest rates in the eurozone have increased the euro’s attractiveness as a reserve currency. Out of 71 central banks that responded to questions about the euro, 62 (87.3%) participants believe it has become a better option for their reserves portfolios.

-

The yen has become less attractive to most reserve managers globally over the last year. In total, 71 participants addressed this question, and 46 (64.8%) say the yen is less attractive as a reserve currency.

-

Instability in the UK’s gilt market in the autumn of 2022 contributed to damage the perspective that reserve managers have on sterling as a reserve currency. Overall, 67 institutions provided feedback on the UK currency. Among these central banks, 54 (80.6%) say they think sterling is a less attractive reserve currency.

-

Beyond government bonds and policy banks, reserve managers are reluctant to invest in other renminbi-denominated assets in China.

-

Most reserve managers think the renminbi will get a larger share of international reserves through the rest of this decade. Nonetheless, this increase is expected to be gradual, and would maintain the Chinese currency at levels much lower than the US dollar.

-

Beyond the core reserve currencies, including the US dollar, the euro, sterling and yen, a group of mid-sized western economies, or allies of the West, receive investments from a wide set of central banks. This is the case for the Australian, Canadian and New Zealand dollars, the Danish krone, the Swedish krona, the Norwegian krone, the South Korean won or the Singapore dollar.

-

Despite the losses most reserve managers have recorded over the last year, an overwhelming majority of institutions are not considering changes to the way they report their annual results.

-

A large majority of reserve managers think risk management frameworks have worked effectively to face the set of risks that central banks have encountered over the last three years.

-

However, a significant share of reserve managers intend to modify their risk management frameworks over the coming two years. Out of the 78 institutions that provided an answer, 19 (24.4%) say they are working towards that goal.

- ESG investment principles are the most common SRI guidelines adopted by reserve managers worldwide.

-

A majority of central banks identify difficulties to integrate SRI principles into their overall mandates as the main obstacle to incorporate sustainable investment practices. Out of the 70 institutions that ranked six main hurdles to SRI adoption, 30 (42.9%) placed this difficulty as their first option.

-

Equities are the most common asset providing central banks with exposure to ETFs. This is the case for 17 (20.5%) participants. Credit came in second place, with 12 (14.5%) reserve managers selecting this option. Additionally, ESG-linked assets are used by 5 (6.0%) reserve managers, while 1 (1.2%) respondent selected other options. No central bank currently investing in ETFs reports doing so through gold.

-

External managers are key to adopting new asset classes. Out of the 82 central banks that provided an answer to this question, 56 (68.3%) explained they see their relations with external managers as an ideal channel to that goal, 43 (52.4%) as a way to introduce active management, and 38 (46.3%) to enter new markets.

Profile of respondents

The survey questionnaire was sent to 111 central banks in February 2023. By mid-March, 83 central banks had sent their feedback. These institutions jointly manage over $7 trillion. This represents 58.8% of total global reserves in the fourth quarter of 2022, according to the International Monetary Fund’s Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (Cofer). The average reserve holding was over $84 billion. Breakdowns of the respondents by geography, economic development and reserve holding can be found in the tables below.1

Which in your view are the most significant risks facing reserve managers in 2023? (Please rank the following 1–6, with 1 being most significant.)

Above-target inflation is the most pressing issue facing reserve managers in 2023, according to a clear majority of reserve managers contributing to this year’s survey. Overall, 55 central banks place it as the main risk. These institutions represent 70.5% of the 78 central banks that addressed the question.

The geographical distribution of these central banks is almost identical to that of all participants. Among the central banks identifying above-target inflation as the main risk, 24 (43.6%) are based in Europe, 13 (23.6%) in the Americas, 7 (12.7%) in the Asia-Pacific region, also 7 in Africa (12.7%), and 4 in the Middle East (7.3%). Jointly, they have over $4.2 trillion under management.

“Since inflation erodes the value and return of the investment portfolio, this risk is of major concern to portfolio managers,” says an upper-middle-income central bank from the Americas.

“The resilience inflation has shown is most important source of uncertainty in the markets,” points out another reserve manager from an upper-middle-income country in the Americas. “Inflation is still the main driver of global monetary policy, which increases the likelihood that other risks will arise, like a slowdown in growth, credit events, liquidity and volatility issues.”

In addition to the high number of central banks that placed above-target inflation as their first concern, 13 (16.6%) more reserve managers placed it in second position.

Another reserve manager from an upper-middle-income country in the same region adds: “The risks associated with the stickiness of high inflation will figure prominently in the investment decision-making process for 2023 since the Fed’s previous rate path has already been impacted.”

A participant based in an African upper-middle-income jurisdiction highlights the core institutional importance that high inflation has for central banks. “In addition to being a source of market risk, controlling the level of inflation is also core to the mandate of central banks,” they say.

Although inflation remains the main concern for most reserve managers, geopolitical risk has become increasingly important. Following the unprecedented sanctions on the Bank of Russia’s reserves due to the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, geopolitical risk features prominently in this year’s survey. In total, 79 central banks assessed the importance this risk will have this year, and 13 (16.5%) say it is their main concern.

Unsurprisingly, nine of these institutions (69.2%) are based in Europe, the region directly affected by Russia’s aggression. Among the other four central banks, two are African, one is from the Americas, and one from Asia-Pacific.

“It seems geopolitical risks weigh more and more on the markets and have stronger spillover effects,” says one high-income European central bank. “The escalation of geopolitical tensions could have far-reaching consequences with further disruption of supply chains, deterioration of the macroeconomic situation as well as risk-off market sentiment, capital outflows from certain (mainly emerging) markets and increased volatility,” points out another central bank in the same region.

A third European reserve manager says the link between this factor and price stability: “Geopolitical tensions and above-target inflation moved closely together recently and we expect this trend to continue in the future.”

A neighbouring European reserve manager from an upper-middle-income country elaborates on the effect geopolitical tensions could have on inflation and markets. These could “decrease yields and might imply lower reinvestment rates” in the future, the central bank says. “On the other hand, persistently high inflation could put upward pressure on yields, which, in addition to restrictive monetary policy, might worsen credit markets conditions.”

Beyond the central banks that selected geopolitical risks as their first concern, 19 (24%) more highlighted it as the second most pressing matter, and 19 more as the third most pressing.

Reserve managers contributed to the survey before the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) in the US and Credit Suisse in Switzerland. This may help to explain the lack of emphasis on financial stability risk. The third risk that participants stress as relevant is premature monetary policy easing. In total, 79 institutions assessed this risk, and just 5 (6.3%) put it in first place. Nonetheless, 23 (29.1%) reserve managers place it in second position, and 19 (24.1%) more in the third.

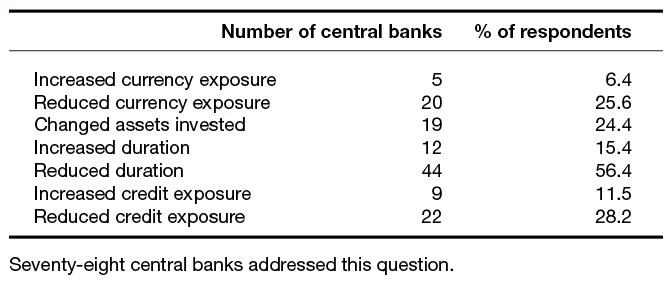

In the current environment of high inflation and tighter monetary policy, what steps have you taken to protect the value of your reserves portfolio? (Please check as many as appropriate.)

A majority of reserve managers reduced duration as a precautionary measure to protect their portfolios’ value over the last year. Of the 78 central banks that signal the measures they took in this environment of high inflation, interest rates and yields, 44 (56.4%) report they reduced duration in a bid to limit the impact of higher yields in long-term maturities.

An upper-middle-income reserve manager in the Americas argues it “continued to invest in shorter dated US Treasuries seeking a safer investment with higher returns, since inflation persists and longer-dated securities are riskier”. Similarly, a high-income institution in the Asia-Pacific region reports most of its active positions are held at a shorter duration than their benchmark in order to outperform in a rising interest rate environment.

A central bank from a lower-income country in Africa says it reduced duration “to be able to tap into the uncertain rise in interest rates and also venture more into floating rate instruments”.

This strategy is broadly shared by an upper-middle-income participant from the Americas. “This year, given the complex context where high inflation is the main risk, we are planning to maintain a short-duration portfolio,” it says. “The main change will be a recomposition of the US fixed-income assets [that tend to have] bigger credit exposure in order to take advantage of higher interest rate levels.”

Nonetheless, because of the fact that central banks are increasing interest rates more than expected, the policy-sensitive two-year bond benchmark has also recorded significant yield increases. Partly as a result of it, 12 (15.4%) reserve managers say they increased duration in the last year.

“We have increased duration to reflect the new, higher-than-before, yield levels,” says one high-income European reserve manager. “This is a first step towards normalisation from ultra-low duration levels.”

Another reserve manager in an upper-middle-income African country echoes this point. This institution decided to “increase duration from mainly short positions to neutral and a few long-duration positions”.

One high-income central bank in the Americas says it “aims to slightly increase [duration] but maintain a relatively short duration of the portfolio to frequently reposition [the portfolio] following the monetary policy tightening in 2022 and expectation of further tightening in 2023”.

Another relevant measure was the reduction in credit exposure. Overall, 22 (28.2%) central banks cut credit risk. Also, 20 (25.6%) participants reduced their currency exposures, and 19 (24.4%) modified the assets they invest in.

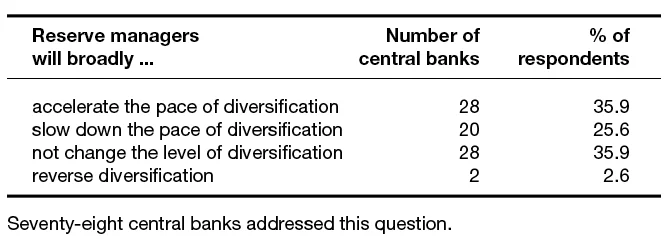

How do you expect markets to impact asset allocation among reserve managers broadly over the next year? (Please check one box.)

Out of the 78 central banks that addressed this question, 28 (35.9%) say they expect the current market environment to foster an acceleration in asset diversification. Among these reserve managers, 12 (42.9%) are based in upper-middle-income countries, 11 more in high-income jurisdictions, 5 (17.9%) in lower-middle-income countries.

This perspective was shared by participants across continents. A high-income reserve manager in the Americas points out: “2022 showed how highly correlated ‘traditional’ reserve assets are, which increases the need to find new sources of diversification.”

An upper-middle-income central bank in the same region makes a similar point: “The recent break in historical correlations between assets makes it even more pressing for reserve managers to seek diversification in their portfolios.”

“I expect the investment universe to increase to generate more returns and reduce risk,” adds one upper-middle-income central bank based in Africa. One reserve manager in a high-income European central bank says: “Definitely the process of reserves diversification will continue, benefiting also from the development of investment vehicles like ETFs.”

However, elevated volatility and an uncertain inflation outlook make other institutions think there will not be changes in diversification in 2023. In total, 28 (35.9%) reserve managers selected this option.

One upper-middle-income participant in the Americas sums up some of the arguments underpinning this option. In their view, the current interest rate level across main economies, negative returns on several traditional asset classes and uncertainty regarding inflation and growth “may prompt reserve managers to recalibrate their portfolios towards allocations that benefit from a better balance between risk and return”. Nonetheless, central banks’ “conservative stance on risk may result in small changes (if any) in allocation until there is a clearer view on economic and geopolitical variables that currently impact expectations on assets”, they add.

A meaningful share of respondents, 20 (25.6%), think the current environment will slow down the pace of diversification in 2023. One high-income central bank in the Americas says it foresees lower allocations to mortgage-backed securities (MBS): “Refinancing activities are becoming less attractive for mortgage borrowers as interest rates increase. Therefore, MBS issued by US agencies with a slightly longer tenor are scarce on the market.”

Another high-income reserve manager in the same region says high inflation will continue to play a big role in global markets. This participant expects central banks to react implementing shorter portfolio durations and reducing the number of currency exposures. Investments in broad currency bases will decline as “most portfolios will try to rely on stronger (G7) countries as the foundation for their portfolios. With the geopolitical climate remaining uncertain, these countries will serve as the bedrock for portfolio building”, they say.

A high-income institution in Europe says that if, as a result of higher interest rates, “risk-free assets are carrying decent yield, there’s less incentive for taking more risk and diversifying”. Another high-income central bank in Europe points out that, facing exchange rate pressures and elevated uncertainty, “reserve managers put more weight on safety and liquidity than on return to respond to the potentially higher reserve need”.

For your portfolio, do you anticipate that over the next year you will: (Please check one box.)

Seventy-eight reserve managers shared how they expect diversification to evolve in their own portfolios. A clear majority of 45 (57.7%) report there will not be any change in their reserves’ level of diversification in 2023.

One reserve manager in a high-income European country shares this perspective. They explain their allocations will be kept according to the strategic benchmark: “During recent turbulent times, hoarding euro liquidity was the main direction in our reserve management operations. As tensions ease, exposures will be adjusted back to the strategic benchmark, which will lead to more diversification compared to the current allocation, but no change from the starting point.”

Overall, 7 (9.0%) of central banks report they will slow down the pace of diversification. A high-income central bank in the Americas says it expects modest adjustments: “Rising inflation together with an accelerated monetary policy normalisation may lead to a slow pace of diversification in our portfolio … as we have to take loss budgets into account for every repositioning of the portfolio. Also, we may increase our holdings in US Treasuries given the very attractive yields.” Only 4 (5.1%) of respondents say the current economic and financial environment will make them reverse diversification.

In fact, 22 respondents (28.2%) intend to accelerate the process in their portfolios. One institution in an upper-middle-income country in the Americas explains that it “always [seeks] to have a portfolio that is resilient in different scenarios, which is more easily achieved by maximising our diversification”.

Other institutions deepening diversification say they will plough ahead with the process, but they are reaching the limits for it. “We are planning to further expand equity investment, but otherwise we have already achieved the appropriate currency and asset class composition of foreign reserves,” says one reserve manager in a high-income jurisdiction in Europe.

What percentage of your FX reserves is in equities?

A majority of participants report low equity allocations. Among the 82 institutions that addressed the question, 58 (70.7%) respondents invest less than 1% of their reserves in this asset. In fact, 56 (68.3%) do not invest at all in this asset. One upper-middle-income reserve manager in Europe explains they are a conservative investor with a mandate of safeguarding FX reserves. Thus, they are prioritising safety and capital preservation: “Return enhancement is of secondary importance, meaning that the institution does not intend to invest in more volatile asset classes such as equity.”

Nonetheless, 14 (17.1%) participants invest between 1% and 10% of their reserves in equities, 8 (9.8%) between 11% and 25%, and 2 (2.4%) between 26% and 50%.

Among the 25 (30.9%) central banks investing in equities, 17 (68%) are based in high-income countries, 4 (16%) in upper-middle-income economies, and 4 more in lower-income countries.

These 25 central banks active in equity investment jointly hold over $2.5 trillion in reserves. Their average allocation is slightly over 10% of their total reserves portfolio.

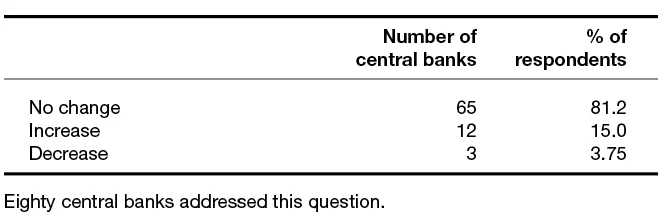

Has your equity changed over the last year?

Among the 80 central banks that responded to this question, 65 (81.2%) say they have not implemented any change in this area. Nonetheless, 12 (15%) institutions report they increased their equity investments during the previous year. A data point showing the solid commitment central banks have adopted in relation to this asset class is the fact that, despite sharp price falls, just 3 (3.75%) reserve managers reduced their equity holdings last year.

Among the 12 institutions that boosted their allocations, all of them are based in high-income countries. Overall, 9 (75%) are based in Europe, 2 (16.7%) in the Middle East and 1(8.3%) in Asia-Pacific. Overall, this group of central banks jointly manage more than $1.1 trillion in reserves. Their average equity allocation is almost 10.6%.

The three central banks that reduced their investments together manage $84.6 billion. And their average equity allocation is 4.7%. Two of these reserve managers are based in high-income European economies, the other is an upper-middle-income country in Africa.

Are you considering any change in 2023–24?

In total, 66 out of the 78 central banks that addressed this question say they will not implement any change to their equity investments in the near future. But 10 (12.8%) say they will increase them, and 2 (2.6%) will invest for the first time.

In the group of 10 reserve managers planning to boost their equity investments, 7 (70%) are in high-income countries, and 3 (30%) in upper-middle-income countries. Their average reserves is over $39 billion.

One of the central banks boosting its exposures reports it will create a new tranche, tracking a climate change benchmark.

No central bank is planning to reduce its equity holdings. But one participant from an upper-middle-income economy in the Americas says the central bank is analysing the possibility of selling its position: “However, current prices might not be at accepted levels to execute the transaction.”

The two central banks planning to invest for the first time in equities are based in high-income European economies, with combined assets of $37 billion.

One of these two institutions is allowed to invest in equities up to 5% of its portfolio. “We will probably start buying some equity index or even more likely some equity ETFs,” it says.

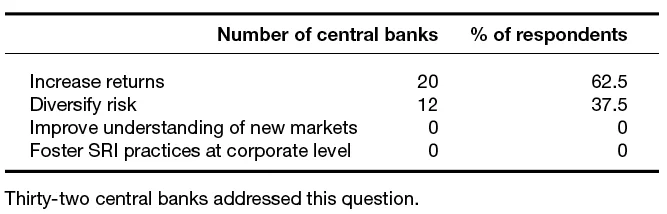

What is the main goal you pursue investing in equities?

The main objective central banks pursue through their equity investments is to increase returns. In the group of 32 reserve managers that responded to this question, 20 (62.5%) selected this option. In this regard, one participant from an upper-middle-income central bank in Africa says the reserves department is “under pressure to grow the reserves organically”.

The other relevant goal is to diversify risk, which was picked by 12 (37.5%) respondents. A respondent in a lower-middle-income economy in the Americas reports “the idea of investing in equities was to diversify risk and gain exposure to higher-yielding securities. This decision was taken around 2012 when interest rates were still very low in US market”.

A central bank in a high-income country in the Middle East points out “equity as an asset class has a high risk premium, which makes it a very good investment for the long run. It is very volatile, but it also functions as a good diversifier in a portfolio with medium-/long-term horizons”.

A high-income central bank in Europe makes a similar point. “We decided to enter equity markets in order to diversify sources of financial risk and return,” it says. “Despite considerable standalone volatility, equities can reduce overall portfolio risk. Over the long-term horizon, they should also enhance return on the investment portfolio, supporting capital preservation.”

No central bank selected options such as improving their understanding of new markets or fostering the adoption of SRI at a corporate level.

Nonetheless, one reserve manager in a high-income European country says that, although their central bank’s goals investing in equities are increasing returns and diversifying portfolio risk, “by 2025, we intend to incorporate some SRI practices in the management of our equity investments (passive investing in SRI equity ETFs)”.

Do you expect bond market volatility and dislocation to be a key source of risk in 2023–24?

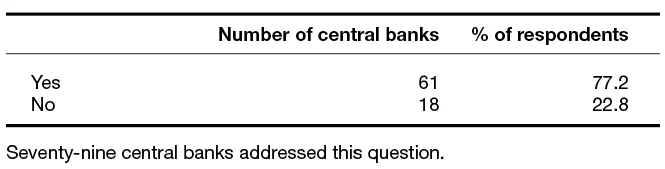

Most respondents foresee bond market volatility and dislocation will be a key risk factor over the next year. Of the 79 institutions that addressed the question, 61 (77.2%) shared this view, while 18 (22.8%) central banks disagreed.

What will be in your view the main risk? (Please select the top three and rank them, with 1 being most significant.)

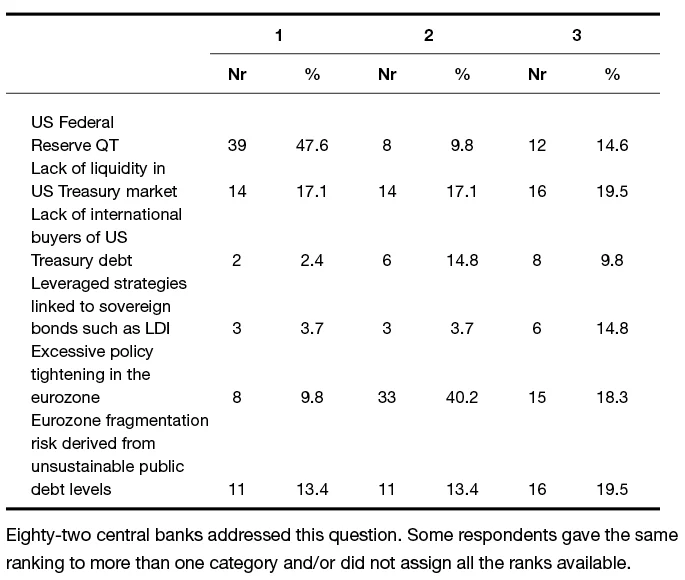

Asked to select three main risks for international bond markets, from a list of six, and rank them in order of importance, reserve managers identified the US Federal Reserve’s QT as the most relevant factor.

Out of the 82 central banks responding to this question, 39 (47.6%) select the Fed’s QT as their top risk, and 14 (17.1%) highlight the lack of liquidity in the US Treasury market.

One central bank from a high-income jurisdiction in Asia-Pacific says that, “while the increase in rate hikes may be less than in 2022, the illiquidity in US bond markets is likely to become a key theme as the Fed continues to roll down its asset purchases leading to an increased supply-demand mismatch”.

“In general, the return to positive rates and the reduction of the excess liquidity changes the supply and demand function in the market,” points out a high-income reserve manager based in Europe. One high-income central bank in the Americas says “liquidity issues are something to keep monitoring, although the fact that the FIMA REPO was made permanent should ease some concerns”.

A participant from an upper-middle-income central bank in the Americas says: “The lack of liquidity in the US Treasury market includes issues that could arise from QT and risks from the lack of international buyers, as is the case for Europe, ie, an excessive policy tightening in the eurozone can lead to fragmentation risk.”

Regarding risks stemming from the eurozone, and the ECB’s monetary policy tightening, 11 respondents (13.4%) identify eurozone fragmentation derived from unsustainable public debt levels as their most pressing concern. And 8 (9.8%) selected as their first option risks derived from excessive policy tightening in the eurozone.

In fact, a significant number of respondents – 33 (40.2%) – say the second most important risk for bond markets in the coming year will be excessive policy tightening in the eurozone, while 15 (18.3%) central banks rank this factor their third risk. Overall, 56 (68.3%) reserve managers rank this factor among their top three risks.

This view is spread across regions. Of the respondents ranking this factor among their top three risks, 26 (46.4%) are based in Europe, 13 (23.2%) in the Americas, 9 in Africa (16.1%), 5 (8.9%) in Asia-Pacific, and 3 (5.4%) in the Middle East.

One central bank based in a high-income economy in Asia-Pacific says that “in spite of the anti-fragmentation tool being introduced by the ECB, it is possible that periphery debt markets in the EU will be stressed as [the] ECB hikes rates higher, likely leading to a lower terminal rate than what is otherwise necessary.”

Meanwhile, 3 (3.7%) central banks choose as their main risks leveraged strategies linked to sovereign bonds such as liability-driven investment (LDI), and 2 (2.4%) a lack of international buyers of US Treasury debt.

A lower-middle-income central bank in the Americas stresses the importance of this last point: “Due to various factors (sanctions by US authorities freezing sovereign countries’ reserves assets, [the] US’s problematic fiscal situation, global uncertainties), we anticipate both a decrease in demand and an increase of supply of Treasuries, which could lead to potential volatility in the level of yields in 2023.”

Do you think your current reserves level is adequate?

A clear majority of central banks deem their current reserves levels to be adequate. Out of the 73 institutions that provided an answer, 64 (87.7%) report they are satisfied with their reserve levels, while 9 (12.3%) say they are not.

The latter group of institutions jointly manage $49 billion in reserve assets, an average of $5.4 billion each. Among these 9 institutions, 2 (22.2%) are based in high-income countries, 2 in upper-middle-income economies, 3 (33.3%) in lower-income economies, and 2 more in low-income countries.

Do you intend to increase your reserves in 2023–24?

Although a large majority of reserve managers assess their portfolios as being at adequate levels, a significant number of respondents say they intend to increase their resources over the coming year.

In total, 23 central banks responded to the question, and 16 report they intend to increase their reserves over the short term (69.6%), while 7 (30.4%) say they do not.

Among the 16 institutions that plan to boost their reserves, 6 (37.5%) are in high-income economies, 4 (25%) are in upper-middle-income countries, 4 more in lower-middle-income jurisdictions, and 2 (12.5%) in low-income economies. Their combined portfolios hold over $154 billion in assets, and their individual average reserve level is $9.7 billion.

“Due to the impact of the global shutdowns over the past two years, our reserve levels had to be sustained through external injections,” says one reserve manager from a high-income country in the Americas. “This is not something we view as sustainable or beneficial in the long run. To mitigate this risk, the organic increase of our reserves is critical.”

Another central bank from a lower-middle-income institution in Africa explains that it “actively participate[s] in the domestic market to purchase FX so as to build the level of reserves, so that we can have some room for diversification”.

A lower-middle-income participant based in the Americas shares a similar outlook: “The intention is to increase the level of our reserves in 2023 by buying USD on the FX market, but this will be challenged by the currency depreciating.”

Higher instability in FX markets has put downward pressure on reserves portfolios over the last year. In this environment, a high-income reserve manager in Asia-Pacific changed the framework regulating its foreign reserves. As part of these efforts, “we have indicated that we expect to increase the size of our foreign reserves to increase our ability to intervene in markets if necessary”, it says.

An upper-middle-income institution in the Middle East stresses the importance of higher reserves for its operations: “We see strengthening foreign currency reserves as essential for effective monetary policy and financial stability. Thereby, one of our main priorities is to strengthen international reserves as long as the market conditions allow.”

In the current geopolitical and inflationary environment, some central banks boosted their gold investments in 2022. Do you think the trend will continue in 2023? (Please select one option.)

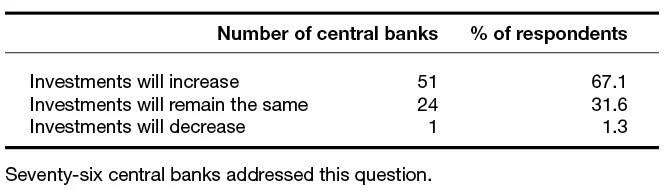

Most respondents think central banks will continue increasing their gold holdings in the coming year. In total, 76 central banks provided an answer to this question, and 51 (67.1%) say that gold investments will increase, 24 (31.6%) institutions say gold allocations will remain the same, and just 1 (1.3%) central bank say gold holdings will decline.

Some say geopolitical tensions are a key factor making gold attractive for investors. The uncertain geopolitical outlook “[makes] gold a favourable investment choice”, says one upper-middle-income central bank in Europe: “Official investors such as central banks and sovereign funds will ramp up their gold reserves, meaning that the trend will continue in 2023.”

More generally, gold tends to become more attractive as a reserve asset in times of instability, not just in international relations, but overall. “Due to the uncertainty about the evolution of the economic activity and to the high level of inflation, the demand for secured assets, such as gold, may increase,” says one lower-income central bank in Africa. The other element fostering gold purchases is above-target inflation. “Gold is a hedge against inflation as it appreciates when currencies and investments depreciate,” points out an upper-middle-income reserve manager in the Americas.

However, inflation may be on a downward path. Tighter financial conditions, improved trade bottlenecks, and lower energy prices are contributing to lower price levels. Furthermore, the 2022 inflationary shock has elevated interest rates to levels not seen since before the global financial crisis. This boosts the returns that reserve managers reap from their fixed income assets, decreasing gold’s appeal. “Falling inflation due to restrictive monetary policies worldwide will be the main reason for decreasing gold investments,” says one reserve manager in an upper-middle-income central bank in Europe.

What percentage of your FX reserves is in gold?

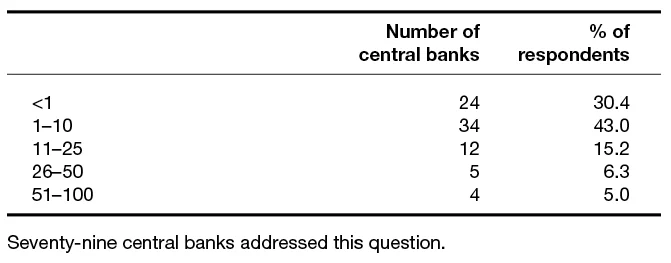

Overall, 79 central banks provided the value of their gold holdings as a share of their total reserves. The average share among participants stood at 10.6%.

But allocations vary considerably. For instance, gold holdings represent less than 1% of total reserves for 24 (30.4%) respondents. The most numerous group records a gold share of between 1% and 10% with 34 (43%) central banks, 12 (15.2%) reserve managers report holdings representing between 11% and 25% of their portfolios, and 5 (6.3%) institutions say their allocations stay between 26% and 50% of their reserves assets, and 4 (5%) between 51% and 100%.

Among the 9 central banks that have gold allocations of more than 25% of total assets, 6 (66.6%) are high-income central banks in Europe, 1 (11.1%) is a lower-income institution in Europe, 1 is an upper-middle-income reserve manager in the Middle East and the last one is based in a lower-middle-income country in Asia-Pacific.

Has your allocation of gold changed in the past year?

Out of the 78 institutions that provided an answer to this question, 15 (19.2%) say they increased their gold holdings in 2022, 5 (6.4%) report a decrease in the gold allocation, and 58 (74.4%) reserve managers say they did not implement any change to this part of their investments.

Among the 15 central banks that boosted their gold allocations, 4 (26.7%) are high-income countries, 4 are reserve managers in upper-middle-income countries, 5 (33.3%) in lower-middle-income economies, and 2 (13.3%) in low-income economies.

The increase in gold’s share of total reserves is partly related to higher market prices. One high-income central bank in Europe explains the higher share of its allocation is due “to an increase in the market price of gold in euro terms, while the size of these holdings in fine ounces remained broadly unchanged”.

Another factor boosting allocations is the lower level of reserves some jurisdictions have recorded. This has been partly due to FX interventions to defend local currencies. This is precisely the case for a lower-middle-income central bank in Asia-Pacific.

A third reason boosting gold is that in some countries with local gold mining production, the central banks’ mandate includes buying part of that output. This has been the case in one lower-middle-income country in Asia-Pacific.

Among the five central banks that reported reductions in their relative gold holdings, no central bank says that it had aimed to structurally reduce the role that gold plays in its portfolio. For instance, one reserve manager in an upper-middle-income economy in the Americas explains “we decreased our gold allocation at the beginning of the last year resulting from our optimisation process. But we are planning to increment it in 2023”.

Are you considering any change in 2023–24?

Regarding scheduled modifications to gold allocations over the short and medium term, a majority of participants say they plan to maintain their holdings unchanged. In total, 73 central banks addressed the question, and 62 (85%) plan to retain their current gold investments.

In contrast, 11 (15%) reported they plan to increase their gold holdings, while no reserve manager intends to reduce them.

Among the group of reserve managers that will increase their allocations, 1 (9%) is based in a high-income country, 5 (45.4%) in upper-middle-income economies, 4 (26.7%) in lower-income economies, and 1 in a low-income country.

One of the institutions planning to increase its gold allocations is an upper-middle-income central bank in the Americas.

This institution explains that “gold is a good diversifier for our portfolio, and, even though it has a large level of volatility, risk-adjusted expected returns remain attractive.”

Have geopolitical tensions led to changes in your asset and/or currency allocation in 2022? (Please select one option.)

The majority of respondents have not implemented changes to their reserves portfolio directly due to higher geopolitical tensions.

In the survey, 79 central banks addressed the question, and 66 (83.5%) say they have not modified their reserves in relation to these risks. Nonetheless, 13 (16.5%) reserve managers have reacted to these events, changing their investments.

Among this group, 8 (61.5%) reserve managers are located in Europe. In fact, most of them are close to both Russia and Ukraine, and 2 (15.3%) are based in the Middle East, 2 in the Americas, and 1 (7.7%) in Asia-Pacific.

If no, do you plan to implement any related changes in the future?

Among the central banks that have not taken action yet regarding geopolitical risks, an important share intends to implement changes in the future.

Overall, 63 central banks addressed the question, 51 (81%) institutions say they do not intend to change their allocations due to these risks. However, 12 (19%) central banks report a plan to do so.

Among participants that do not plan to change their portfolios, geopolitical risks are nonetheless taken increasingly seriously. For instance, a high-income central bank in the Americas says that “no changes were made to our reserves portfolio in light of geopolitical tensions, but the situation is continually monitored”.

And a counterpart of the same income level in Europe says they do not intend to make changes, “but cannot definitively say no well into the future”.

A third high-income country in the Americas explains that it does not intend to change its strategic asset allocation. However, “the active management approach could change”, the institution says: “For example, exposure to supranationals, agencies or banks for 2023 will depend on the geopolitical situation.”

The changes already planned include reducing currency exposures and adding gold. One reserve manager from a high-income central bank in Europe points out they are decreasing their investments in renminbi as a result of the geopolitical environment. A lower-middle-income institution in Africa adds that, “in case geopolitical uncertainty persists, we expect an increase in gold holdings will help us cope better”.

Last year, the ECB abandoned negative interest rates. With yields in positive territory across the eurozone, have you changed your view on the euro as a reserve currency?

Higher interest rates in the eurozone have increased the euro’s attractiveness as a reserve currency. Overall, 71 central banks responded to questions about the currency, and 62 (87.3%) participants say they think it has become a better option for their reserves portfolios. In contrast, 9 (12.7%) central banks say the euro is less interesting.

“We liquidated our euro portfolio in the beginning of 2021 because of negative yields,” says one reserve manager from a high-income European institution. “But, as the yields are back in positive territory, we are considering starting investing in euro bonds again. It might not happen this year, though.”

Another European institution of the same income level explains that, “after sitting on euro cash most of 2022, we will invest more in fixed income. Maybe, [we will have] slightly more currency exposure to EUR in 2023 than 2022”.

An upper-middle-income central bank in the Americas says its investments in euro follow “a number of strategic objectives”. For this institution, “the yield level plays a limited role in the allocation process, but, everything else kept unchanged, being in positive territory makes the euro more attractive than otherwise”.

A respondent from a high-income central bank in Europe stresses the structural strengths that the euro has offered it over the previous years: “Despite its low yield in the past, the euro has been one of the major reserve currencies, offering high liquidity, broad and mature markets of premium securities, developed payment infrastructure and relatively low volatility against our base currency. Thus, the change in market conditions has enhanced investment opportunities but has not had a significant impact on our attitude towards the euro.”

Among the 9 central banks saying it is a less attractive asset, 5 (55.5%) are based in the Americas, 1 (11.1%) in Africa, 1 in Europe, 1 in the Middle East and 1 in Asia-Pacific.

Within this group, an upper-middle-income country in the Americas says the European currency “is not attractive from a risk-return perspective”.

One central bank in the Americas based on an upper-middle-income economy says it is working with the World Bank to improve its reserve management capabilities. As a result, it has limited investments in currencies different to the numeraire US dollar to decrease currency risk exposure. “The programme does contemplate investment in currencies different to USD – however, it is not planned to be implemented at least during 2023.”

If investing in the euro, please give the share of your portfolio invested.

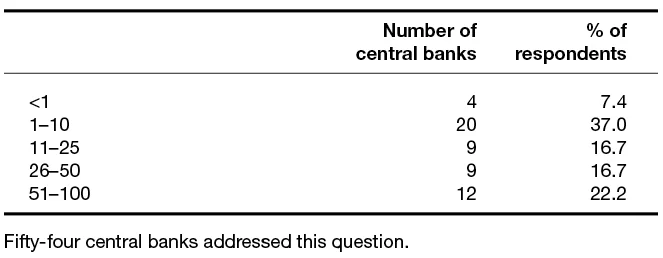

Among the survey’s participants, 54 reported having investments in euro-denominated assets as part of their reserves portfolios. Allocations ranged widely.

For instance, 4 (7.4%) central banks have investments in the eurozone’s currency of below 1% of their reserves’ value, 20 (37%) between 1% and 10%, 9 (16.7%) between 11% and 25%, 9 between 26% and 50%, and 12 (22.2%) between 51% and 75%.

In the group of reserve managers allocating over 25% of their reserves to the euro, 18 out of 21 (85.7%) institutions are based in Europe, 1 (4.8%) in Africa, 1 in the Middle East and 1 in Asia-Pacific.

Regarding their income level, 17 (81%) are high-income economies, 3 (14.3%) are of upper-middle-income, and 1 (4.8%) lower-middle-income.

Jointly, these central banks have over $1.4 trillion in reserves, with an average of $66.7 billion each of them.

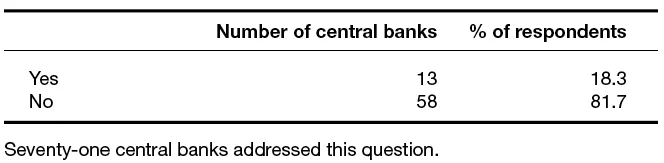

Do you plan to increase euro investments in 2023?

Asked if they intend to increase the share of reserves allocated to the euro this year, 71 central banks provided an answer. Overall, 13 (18.3%) intend to boost their investments, while 58 (81.7%) say they will not do so.

In this latter group that intends to maintain its current level of exposure to the euro, one upper-middle-income reserve manager based in the America points out that “while we find it is important to keep a portion of our portfolio in euros, we do not see any incentives to increase this allocation yet since yields remain more attractive in the US and our numeraire is the US dollar”.

Among the 13 institutions planning to increase their euro-denominated investments, 5 (38.5%) are in Europe, 4 (30.8%) in Africa, 2 (15.4%) in the Americas, 1 (7.7%) in the Middle East, and 1 in Asia-Pacific.

In this group, one low-income central bank based in Africa says it plans to increase the allocation to the euro from 10% of its portfolio to 16% this year.

An upper-middle-income reserve manager from Africa adds that, “given the positive outlook on euro-USD rate, we believe that euros will bring a diversification benefit to the reserves portfolio”.

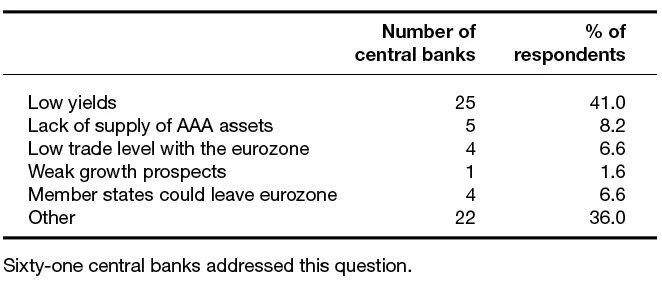

What is the main hurdle for your institution to start investing in euro-denominated assets, or increase current allocations? (Please select one option.)

Most central banks identify low yields as the main obstacle to start allocating reserves to the euro or increase current investment. Sixty-one central banks addressed the question, and 25 (41%) say low returns are the main hurdle.

One participant from a high-income economy in Asia-Pacific explains “it is less appealing for us to hold a high allocation of euro assets unless the yield on those assets [is] able to outperform yields in other currencies”.

A reserve manager of the same income level in the Americas has a similar argument: “While interest rates in Europe have risen, they continue to trail rates in the US. As a result, increased allocations in euro-denominated investments are unlikely, but asset managers may seek tactical opportunities in the market.”

The second obstacle is the lack of supply of AAA assets denominated in the European common currency. This factor was selected by 5 (8.2%) institutions. In joint third place, 4 (6.6%) central banks highlight low trade levels with the eurozone as their main problem to increase allocations to the euro.

For instance, a reserve manager from a lower-income economy in the Americas argues that it “does not have sufficient external commitments in euros to justify investing parts of its reserves in that currency”.

One lower-income institution in Africa highlights two aspects as key for it to maintain a relatively low allocation to the currency: “Low exposure to EUR and relatively low yields offered in the market.”

Additionally, 1 (1.6%) institution says its main hurdle to invest in the currency is the eurozone’s weak growth prospects. And 4 (6.6%) stress that member states could leave the eurozone.

A large number of participants selected other factors as their main problem to investing in euro-denominated assets. In total, 22 (36%) institutions selected this broad option.

A participant in an upper-middle-income country in the Americas says: “The major risk is the exchange rate volatility. A portfolio mostly denominated in a currency other than the US dollar does not provide the stability the dollar provides to our foreign reserves.”

Despite the global tightening process trend in monetary policy, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) is maintaining yield curve control and an accommodative stance. What is your overall outlook on the yen? (Please select one option.)

The Japanese currency has become less attractive to most reserve managers globally over the last year. This is partly due to the Bank of Japan’s reluctance to tighten monetary policy. This has maintained yields at lower levels than in other important markets.

In total, 71 participants addressed this question, and 46 (64.8%) say the yen is less attractive as a reserve currency. In contrast, 25 (35.2%) central banks report it is a more attractive asset.

Among members of the latter group, 12 (48%) central banks are based in Europe, 5 (20%) in the Americas, 3 (12%) in Africa, 3 in Asia-Pacific, and 2 (8%) in the Middle East. Most of these reserve managers, 16 (64%), are based in high-income economies. Among the other participants who think the yen has become a more attractive currency, 6 (24%) are in upper-middle-income economies, 2 (8%) in lower-income countries, and 1 (4%) in a low-income economy.

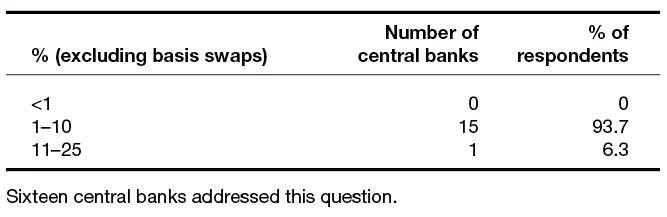

If investing in yen, please give the share of your portfolio invested.

Regarding reserves investments denominated in yen, the survey divided allocations between those excluding basis swaps and those including them.

Among the former, 16 central banks provided an answer. The overwhelming majority of them, 15 (93.7%) invest between 1% and 10% of their reserves in yen, and 1 (6.3%) invests between 11% and 25%.

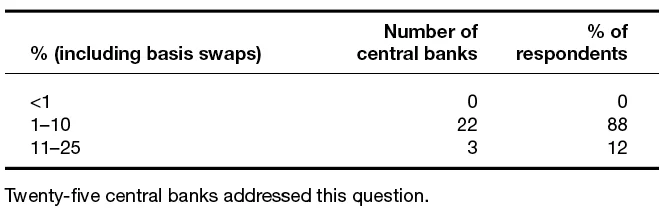

The group including basis swaps comprises 25 central banks. The shares allocated to the Japanese currency are similar to the other group. Overall, 22 (88%) invest between 1% and 10% in this currency, and 3 (12%) invest between 11% and 25%.

What is the main hurdle for your institution to start investing in yen-denominated assets, or increase current allocations? (Select one option.)

As is the case for euros, low yields are the main hurdle to investing in yen that reserve managers identify. In total, 71 central banks rated the main impediments they see in the Japanese currency and financial markets, with 32 (45%) saying low returns are the main hurdle.

For instance, a participant from an upper-middle-income institution in the Americas says the yen “is not attractive from a risk-return perspective.”

A respondent from a high-income European country points out the BoJ’s quantitative easing programmes have distorted markets, giving an outsize role to the central bank. “Japan has no interest rate. The exchange rate and stock exchange are under the power of the BoJ,” it says.

An upper-middle-income African central bank sees some reason for optimism in the near future: “With rates almost peaking in the US, the outlook for yen could be positive versus the dollar (with the dollar having already strengthened significantly against [the] yen). However, given the yield differential, we do not have an appetite yet for yen.”

The second most important factor is the low trade level with Japan. This option was selected by 8 (11.3%) reserve managers. The third option is the lack of available assets, highlighted by 4 (5.6%) respondents. For instance, an upper-middle-income central bank in Africa points out: “Poor liquidity in certain sectors of fixed income does not encourage active management.” The fourth factor is weak growth prospects, which was chosen by 1 (1.4%) central bank.

An upper-middle-income reserve manager based in Europe stresses: “The Japanese economy experiences a low-growth prospect and the yen is at a two-decade low, meaning that it is not attractive.”

Nonetheless, these options did not cover all the reasons hampering greater yen allocations. In fact, 26 (36.6%) central banks indicated other options were playing a bigger role in their approach to the Japanese currency.

Although negative rates and asset purchases have depressed demand for the Japanese currency as a reserve asset, the prospect of policy normalisation adds new risks of its own. “The risk of yield curve control being abandoned or higher rates is a major risk to the portfolios,” says one high-income central banks from Asia-Pacific. “Yen is more risky than it was in the past decade and we factor this into our considerations.”

Considering dislocations in the gilt market over the last year, what is your view of sterling as a reserve currency? (Please select one option.)

Instability in the UK’s gilt market in the autumn of 2022 have contributed to damaging the perspective that reserve managers have on sterling as a reserve currency.

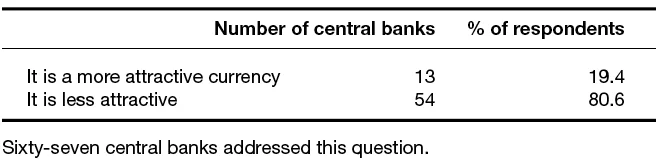

Overall, 67 institutions provided feedback on the UK currency. Among these central banks, 54 (80.6%) say they think sterling is a less attractive reserve currency, while 13 (19.4%) say it is more attractive.

Among the latter, 5 (38.5) are high-income central banks, 4 (30.8%) are in upper-middle-income countries, 3 (23.1%) in lower-income countries and 1 (7.7%) in low-income jurisdictions. Regarding their location, 6 (46.2%) central banks are based in Europe, 3 (23.1%) in Africa, 3 in the Americas, and 1 (7.7%) in the Middle East.

If investing in sterling, please give the share of your portfolio invested.

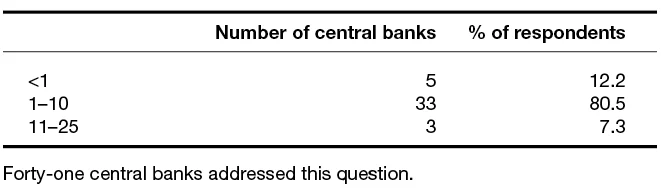

Overall, 41 institutions addressed this question. A large majority of respondents 33 (80.5%) invest between 1% and 10% of their reserve portfolios in sterling, 5 (12.2%) invest less than 1% of their reserves in the UK currency, and 3 (7.3%) between 11% and 25%.

Among the central banks allocating between 1% and 10% of their portfolios to sterling, 19 (57.6%) are based in Europe, 5 (15.2%) in Africa, 4 (12.1%) in the Americas, 3 (9.1%) in Asia-Pacific, and 2 (6.1%) in the Middle East.

Regarding their level of income, 18 (54.5%) of these reserve managers are based in high-income jurisdictions, 8 (24.2%) in upper-middle-income countries and 7 (21.2%) in lower-income jurisdictions.

The countries allocating over 11% or more of its reserves to sterling are all high-income economies: 2 (66.7%) are based in Europe, and 1 (33.3%) in Asia-Pacific.

What is the main hurdle for your institution to start investing in sterling-denominated assets, or increase current allocations? (Please select one option.)

Several factors play a relevant role in hampering a wider adoption of sterling as a reserve currency. Among the 66 central banks assessing these factors, 19 (28.8%) select market volatility as the main hurdle.

“The increase in market volatility that we saw in 2022 puts in question the risk-return profile of the sterling-denominated instruments,” says one respondent from a high-income institution in the Americas.

Another important force is a low trade level with the UK, highlighted by 13 (19.7%) institutions. One respondent from a lower-middle-income economy in the Americas explains that it “does not have sufficient external commitments in GBP to justify investing parts of its reserves in that currency”.

Additionally, 10 (15.2%) participants opt for weak growth prospects, while 5 (7.7%) choose low yields.

Furthermore, 19 (28.8%) respondents say other factors are more important to them regarding difficulties in investing in sterling. For instance, an upper-middle-income reserve manager from an African central bank mentions “political instability” as the main obstacle in the way of larger sterling allocations.

A high-income reserve manager based in Europe mentions a similar factor. “Brexit is still not fully resolved,” it says. Another institution based in a high-income European country adds that it has not invested in sterling for a long time. It says it “may look at it in the future, but would probably need more certainty and a more responsible political environment”.

A lower-middle-income respondent from Asia-Pacific stresses “high uncertainty due to Brexit”. One upper-middle-income reserve manager based in the Americas explains it divested its strategic position in the pound before the Brexit vote, and has remained out of this market because “it shows a higher volatility than other currencies and lack of diversification benefits. We only invest through short-term tactical positions”.

If investing in the renminbi, please give the share of your portfolio invested.

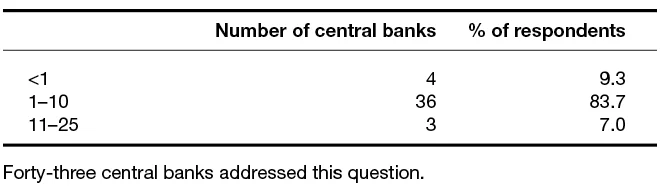

A majority of central banks investing in the renminbi allocate between 1% and 10% of their total reserves to this currency. Overall, 43 reserve managers provided an answer to this question, and 36 (83.7%) of them say their allocations are within that range.

Among them, 18 (50%) come from European countries, 6 from Africa (16.7%), 5 (13.9%) from the Americas, 4 (11.1%) from Asia-Pacific and 3 (8.3%) from the Middle East. In this group, 18 central banks are based in high-income economies, 9 (25%) in upper-middle-income countries, 6 (16.7%) in lower-income jurisdictions, and 3 (8.3%) in low-income countries.

The rest of respondents belong to much smaller groups. For instance, just 4 (9.3%) central banks report investments below 1% of their reserves. Of this group, 2 (50%) are based in Europe, 1 (25%) in the Americas, and 1 more in Africa. Regarding their income level, 2 are high-income countries and 2 are upper-middle-income economies.

Only 3 (7%) central banks allocate between 11% and 25% of their reserves portfolios to the renminbi. Among them, 2 (66.7%) are based in Africa and 1 (33.3%) in Asia-Pacific. Regarding their income levels, 2 are lower-income economies and 1 is low-income.

Which of the following best describes your attitude to investments and products in the onshore renminbi market?

When it comes to investing in China’s financial markets, reserve managers favour government bonds as the asset that gives exposure to the renminbi.

Overall, 68 central banks assessed this key asset. Among them, 40 (58.9%) are currently investing in Chinese government bonds, 2 (2.9%) are considering investing in them now, while 11 (16.2%) would consider doing so in 5–10 years. However, 15 (22.1%) say they have no interest in investing in government bonds.

Chinese government bonds are divided into: onshore bonds, which are traded in mainland China; and offshore bonds, traded in Hong Kong. One lower-income central bank in Africa says it is “invested in the offshore (CNH) market”, but has “no exposure to onshore CNY at the moment”. One high-income European reserve manager explains: “We have been in government bonds for a few years now and do not see any great change in the near future.”

Some institutions highlight the importance of developing internal capabilities in order to be able to invest in Chinese financial assets. This relates to the different legal framework, financial regulation and time difference.

“We are currently working on our own capabilities for investing in Chinese government bonds to expand our opportunities in this asset without having to go through an external manager,” says one upper-middle-income central bank from the Americas.

A reserve manager from an upper-middle-income economy in Africa that already invests in the renminbi says its “view on China still remains the same, that it is an attractive market to invest in and serves as a good yield diversifier to our investments”.

Policy bank bonds are the second most popular asset. Out of the 67 institutions that assessed them, 15 (22.4%) are currently investing in them, 6 (1.5%) are considering it, 16 (23.9%) say they would consider it in 5–10 years, and 30 (44.8%) say they are not interested in the asset.

One high-income central bank in the Americas says it has “recently started investing in policy banks”.

Nonetheless, beyond these two core assets, most reserve managers are reluctant to invest in Chinese financial markets. For instance, 67 institutions assessed the equity market, and only 4 (6%) say they are investing in it, no participants are considering investing, 3 (4.5%) would consider doing so in 5–10 years, while 60 (90%) are simply not interested.

A similar picture emerges regarding other products such as credit bonds, repo or interest rate swaps. The last of these was addressed by 67 participants, with 1 (1.5%) already investing in this product, 1 more considering doing so, 10 (14.9%) would consider this option in 5–10 years, but 55 (82.1%) are not interested.

In 2022, the IMF increased the weight of renminbi in the SDR basket to 12.28%. What percentage of global reserves do you think will be invested in the renminbi by:

Most reserve managers think the renminbi will get a larger share of international reserves throughout the rest of this decade. Nonetheless, this increase is expected to be gradual, and would maintain the Chinese currency at levels significantly lower than the US dollar.

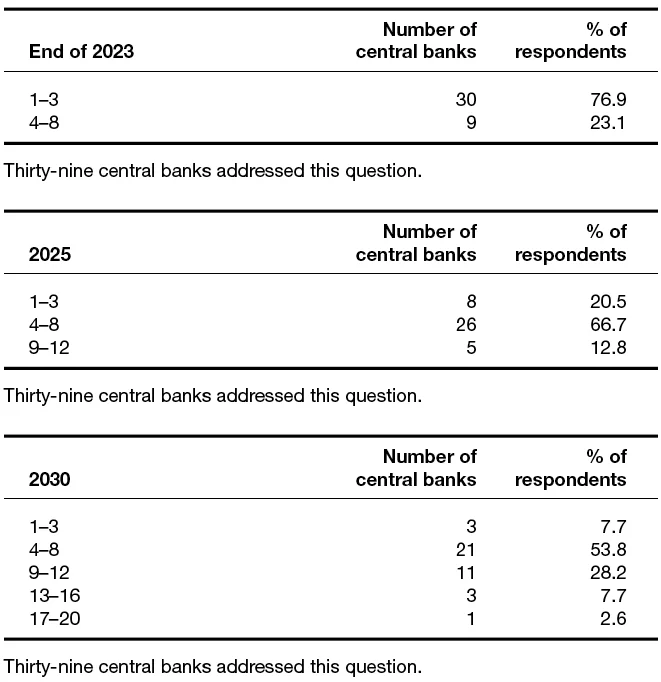

According to IMF data, the renminbi represented 2.7% of total allocated reserves in the fourth quarter of 2022. Overall, 39 central banks addressed this question, and 30 (76.9%) think the renminbi’s share of global reserves will be between 1% and 3% by the end of 2023. And 9 (23.1%) expect it to be between 4% and 8%.

By the end of 2025, 8 (20.5%) participants expect the renminbi to represent between 1% and 3% of global reserves, 26 (66.7%) between 4% and 8%, and 5 (12.8%) between 9% and 12%.

Finally, looking to the end of 2030, just 3 (7.7%) respondents foresee the Chinese currency will stay at a range between 1% and 3%, 21 (53.8%) expect it to be between 4% and 8%, 11 (28.2%) between 9% and 12%, 3 (7.7%) between 13% and 16%, and 1 (2.6%) between 17% and 20%.

An upper-middle-income reserve manager based in Europe points out China’s post-Covid expansion will enable the country to tap into the unutilised capacity of its economy: “Nevertheless, there are limits to growth for China, as has been estimated by experts, which is likely to come from the declining productivity of capital-intensive growth, as the economy will reach its full capacity and enter a more mature phase.”

Another participant from the same income level in the Americas makes a similar argument: “The weight of the renminbi in global reserves has been increasing like a linear trend. As the Chinese economy continues to grow and influence global markets, it is conceivable that central banks will also gradually adapt their allocations to reflect the importance of the most relevant economies.”

Nonetheless, other respondents stress the financial and geopolitical limits the renminbi is likely to face in the coming years. One reserve manager from a high-income central bank in Europe points out China “is still relatively closed to foreign capital, and there are great uncertainties about political developments”. These relate to both internal and international issues, “especially the Taiwan question and China’s attitude towards Russia invading Ukraine”.

Despite the complex global context, most central banks agree the renminbi offers an attractive alternative to traditional reserve currencies, which will gradually boost its allocations in the coming years. One upper-middle-income central bank based in the Americas stresses that “the renminbi is a good diversifier against traditional reserve currencies, so it makes sense that allocations to renminbi increase”.

Which view best describes your attitude to the following currencies? (Please check one box per currency.)

Click here to open table in new tab

Beyond the core reserve currencies, including the US dollar, euro, sterling and yen, a group of mid-sized western economies, or allies of the West, receive investments from a wide set of central banks.

This is the case for Australian, Canadian and New Zealand dollars, the Danish krone, Swedish krona, Norwegian krone, South Korean won and Singapore dollar.

For instance, 79 central banks provided their assessment of the Australian currency, and 41 (51.9%) are investing in it, 8 (10.1%) are considering doing so, 6 (7.6%) would consider it in 5–10 years, while 24 (30.4%) say they are not interested.

The Canadian dollar received a similar assessment. Out of 78 respondents, 38 (48.7%) are investing in the currency, 7 (9%) are considering it, 8 (10.3%) would consider the currency in 5–10 years, and 25 (32.1%) respondents say they are not interested.

In the case of the New Zealand dollar, 76 central banks provided feedback on it. In total, 23 (30.3%) are investing in it, 4 (5.3%) are considering it, 12 (15.8%) would do so in 5–10 years, while 37 participants (48.7%) are not interested.

The won and the Singapore dollar receive lower levels of interest, but they are relevant. For instance, the Korean currency was assessed by 75 reserve managers. Overall, 15 (20%) are investing in it, 1 (1.3%) is considering it, 11 (14.7%) would considering it in 5 to 10 years, while 48 (64%) respondents say they are not interested.

In the case of the Singaporean currency, 76 respondents provided an answer. Among them, 16 (21%) are investing in the currency, 1 (1.3%) is considering it, 4 (5.3%) would do so in 5–10 years, while 55 (72.4%) say they are not interested in the currency.

The Swedish krona has a similar level of interest. Overall, 75 respondents assessed the currency. Among them, 18 (24%) are investing in it, 6 (8%) are considering it, 10 (13.3%) would consider it as a reserve currency in 5–10 years, and 41 (54.7%) report they have no interest in the Scandinavian currency.

Reserve managers also provided more detailed insights into their renminbi investments. Regarding their onshore assets, 76 respondents addressed the question. Overall, 39 (51.3%) are investing in it, 2 (2.6%) are considering it, 12 (15.8%) would do so in 5–10 years, while 22 (29%) are not interested. For the offshore renminbi, 75 reserve managers assessed the asset. In total, 21 (28%) are investing in it, 4 (5.3%) are considering it, 11 (14.7%) would consider it in 5–10 years, and 39 (52%) say they are not interested.

With losses sustained by many reserve portfolios in 2022, have you introduced modifications to the way in which you report your annual results?

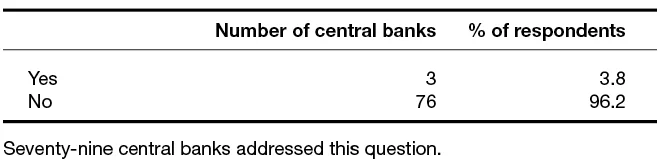

Despite the losses most reserve managers have recorded over the last year, an overwhelming majority of institutions did not change the manner of reporting annual results, and are not considering changing this. Out of 79 central banks, just 3 (3.8%) institutions have introduced modifications to the way they report this information.

One upper-middle-income reserve manager from Europe says that it “is focused on safety of reserves, rather than return generation, and as long as there is no risk to the reserve portfolio falling short of a threshold for safety, there is no pressure on FX reserves management to generate absolute level positive return”.

Another high-income central bank from the same region adds that it does not think the public would welcome changes in the current context. “The risk is that seeing any change as a consequence of poor results would be considered as an attempt to hide something,” it says.

Similarly, a high-income central bank in Europe says: “Extra care is being taken when explaining the results. We are explaining to the public how a central bank result is calculated in broad terms, and what affects it.”

If no, do you plan to introduce modifications on how you communicate your results in the near future?

In fact, a larger group of central banks is planning to introduce modifications to the way in which they report their results.

Out of the 74 central banks that addressed this question, 9 (12.2%) say they are working on changes or debating possibilities. “While reporting requirements have remained the same, even though losses were generated in the reserve portfolio, discussions on mark-to-market losses and yields have been and are expected to be more prominent,” says one participant from a high-income country in the Americas.

And one upper-middle-income central bank in the same region explains that it intends “to increase the frequency with which we engage stakeholders on the performance of the FX reserves”.

Among members of this group, 3 (33.3%) are based in Europe, 3 in the Americas, 2 (22.2%) in the Middle East, and 1 (11.1%) in Asia-Pacific. According to their income level, 3 (33.3%) are based in high-income economies, 3 in upper-middle-income jurisdictions, and 3 in lower-middle-income countries.

Due to the pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, higher inflation and market volatility, over the last three years risk management frameworks have been severely tested. Do you think, in general, risk management of reserves has been effective? (Please select one option.)

A large majority of reserve managers think risk management frameworks have worked effectively to face the set of risks central banks have encountered over the last three years.

In total, 79 institutions provided their feedback on this topic, and 73 (92.4%) deem these frameworks to have delivered a good performance. Nonetheless, 6 (7.6%) institutions say they are not satisfied with them. Among these, 3 (50%) are based in Europe and the other 3 in the Americas. Regarding their level of income, 4 (66.7%) are in upper-middle-income countries, and 2 (33.3%) high-income economies.

One upper-middle-income European participant stresses the importance of having “better forecast models that include more factors such as geopolitical risks and their effects on markets”.

Another participant points out that risk management also needs to be able to respond to tail risks. “Events like those experienced recently call for improvements in tools available for risk management, like enhanced risk mapping between the decision-makers’ appetite and their long-term objectives,” it says. “And also further understanding on integration of all sources of risks any central bank may face.”

A counterpart in a high-income central bank in Europe adds that “events like Covid, inflation and the Russian invasion of Ukraine underlined, or highlighted, the fact that risk management in central banks is passive, static and not capable of reacting proactively”.

Do you plan to modify your risk management framework in 2023–24?

A significant share of reserve managers intends to modify their risk management frameworks over the next two years.

Out of the 78 institutions that provided an answer, 19 (24.4%) say they are working towards that goal. In this group, 7 (36.8%) are based in Europe, 5 (26.3%) in the Americas, 3 (15.8%) in Africa, 3 in the Middle East and 1 (5.3%) in Asia-Pacific.

Regarding their level of income, 9 (47.4%) are in high-income jurisdictions, 8 (42.1%) reserve managers are based in upper-middle-income economies, 1 in a lower-income jurisdiction, and another in 1 low-income country.

One upper-middle-income central bank based in Europe says that it “introduced very recently an internal model of evaluating credit risk limits with our counterparties”.

Another reserve manager of the same income level in Europe explains that it plans to add “more advanced tools of risk management to our current inventory, such as the application of Monte Carlo simulation, to obtain a more comprehensive picture of potential distribution of future returns, so that we are better equipped to deal with severe losses”. This respondent adds: “We are modifying our portfolio management and reporting system, which will also enhance our capabilities to manage risks.”

A high-income participant from a central bank in the Middle East explains it is “trying to rethink our credit risk framework, mainly in aspects of risks from single issuers, and also trying to better calibrate our investment rules to be more consistent with each other”.

Does your central bank incorporate an element of SRI into reserve management? (Please select one option.)

A majority of central banks have either incorporated an element of SRI into reserve management, or are considering it.

In total, 79 central banks addressed this question, 68 (86.1%) belong to one of these two groups, while just 11 (13.9%) report they do not adhere by any SRI principle and do not plan to do so. Among all respondents, 36 (45.6%) say they implement one of these principles, while 32 (40.5%) are considering it.

In the group of 11 institutions not even considering SRI adoption, 4 (36.4%) are based in the Americas, 4 more in Europe, 2 (18.2%) in Asia-Pacific and 1 (9.1%) in Africa. Regarding their level of income, 2 are high-income economies, 2 in upper-middle-income countries, 5 (45.5%) in lower-income countries, and 2 in low-income countries.

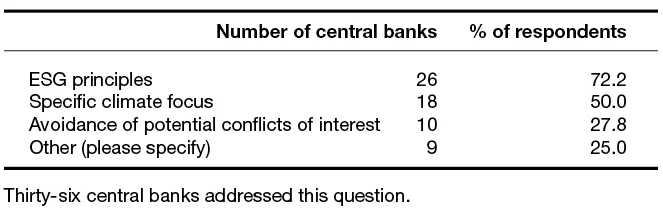

ESG investment principles are the most common SRI guidelines adopted by reserve managers worldwide. Respondents could select as many options as they saw fit. Some selected all of them, while others did not pick any.

If “Yes”, does this include: ESG principles, specific climate focus, avoidance of potential conflicts of interest, other (please specify).

Overall, 36 central banks provided feedback on this question. Among them, 26 (72.2%) implement ESG.

Additionally, 18 (50%) implement specific climate focus, while 10 (27.8%) incorporate avoidance of potential conflict of interests. Finally, 9 (25%) selected other criteria.

For instance, an upper-middle-income central bank in Europe says that although it does not have an element of SRI in its reserve management, it does invest in green bonds and ESGs.

A high-income reserve manager on the same continent adds that it is “looking into taxonomy and recommendations of relevant institutions as well as reliability of available data”.

A reserve manager in an upper-middle-income institution in Europe explains it does not have any SRI implemented at the moment. But it is considering introducing some ESG principles in the near future. “Currently, we do buy ESG bonds as ordinary bonds in our portfolio,” it adds.

Another participant adds some details about the strategies it is following in order to incorporate SRI investment principles.

“We are incorporating two SRI strategies for our fixed-income investments,” says the reserve manager based in a high-income European central bank.

“Firstly, investments in thematic bonds (eg, green, social and sustainable bonds). Secondly, incorporation of the exclusion list for our investments in non-financial corporate bonds, based on environmental and social factors.”

If “Yes”, how do you integrate these into your investment process?

Most reserve managers incorporate SRI investment principles as part of their SAA.

Among the 36 central banks providing an answer, 32 (88.9%) resort to this method. In contrast, 14 (38.9%) implement standalone portfolio mandates. Participants could select one option, both or none.

Which strategies do you employ?

The strategy most commonly used among reserve managers to incorporate SRI is ESG integration. Out of the 36 institutions that provided answers, 23 (63.9%) indicate this option, 19 (52.8%) opt for impact investing, 18 (50%) select negative screening, 7 (19.4%) best in class strategy, 4 (11.1%) voting and engagement.

It is common that institutions active in this area resort to more than one strategy. For instance, “negative screening is applied to the entire foreign exchange reserves,” says a high-income institution in Europe: “ESG integration only in small standalone portfolio mandates.”

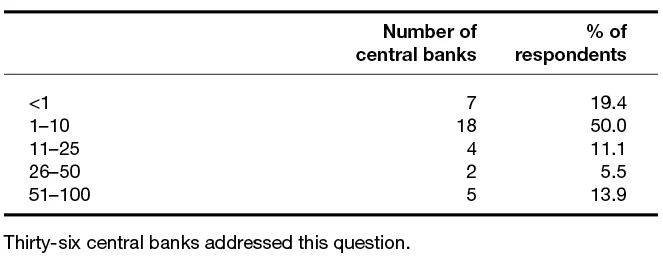

Asked to provide the share of their portfolios that reserve managers deem to be SRI, 7 (19.4%) say this represents below 1% of their reserves.

What percentage of your FX reserves portfolio do you consider SRI?

Beyond that level, 18 (50%) participants say their SRI-compliant assets represent between 1% and 10% of their reserves, 4 (11.1%) say these reach between 11% and 25%, 2 (5.5%) between 26% and 50%, and 5 (13.9%) between 51% and 100%.

Some reserve managers rely on external managers to adopt SRI principles. For example, “we have allocated a portion of the reserves to an external manager that implements an ESG framework. This investment represents around 3% of the reserves as at the end of December [2022]”, says an upper-middle-income central bank based in Africa.

Which in your view are the most significant obstacles to incorporating SRI into reserve management? (Please rank the following 1–6, with 1 being most significant.)

A majority of central banks identify difficulties to integrate SRI principles into their overall mandates as the main obstacle to incorporate sustainable investment practices. Out of the 70 institutions that ranked six main hurdles to SRI adoption, 30 (42.9%) placed the challenge of integration as their first option. The second was concerns over liquidity/returns, which was chosen by 16 (22.9%) respondents. In fact, a “lack of sovereign fixed-income and agencies securities with short-duration mainly in USD” was highlighted by an upper-middle-income reserve manager based in the Americas.

A high-income central bank in Europe agrees: “Lack of SRI product supply (bonds, equity ETFs, etc) is the main obstacle.”

Beyond these two main factors, other aspects play a relevant role. Among them, the lack of and cost of obtaining data was picked by 9 (12.9%) central banks, lack of a clear SRI definition was selected by 7 (10%), while 5 (7.1%) participants chose lack of consistency in disclosures. And 5 more selected greenwashing.

Another high-income European reserve manager stresses there is not a well-established global best practice. Instead, “vague definitions and questionable connection between investment and real positive impact”. A counterpart in a high-income jurisdiction in the Americas adds that there are “challenges with developing and adopting a widely accepted industry standard to easily identify ESG investments”.

Which best describes your attitude to the following asset classes? (Please check one box per asset class.)

Government bonds above BBB credit rating remain the indisputable leader in central banking reserve management. Among the 77 institutions disclosing their approach to this asset, 75 (97.4%) say they are investing in it.

The only assets that come close in terms of current adoption are supranationals, out of the 79 institutions providing information on this asset, 74 (93.7%) are investing.

The third main assets in terms of number of institutions investing are deposits with central banks and the official sector. In total, 71 (87.7%) institutions are investing in it now. Additionally, 60 (76.9%) of central banks report they invest in deposits with commercial banks.