Central bank digital currencies: 10 questions

Paul Mackel, James Pomeroy and Zoey Zho

Executive summary

Trends in reserve management: 2022 survey results

Interview: Gerardo García

Central bank digital currencies: 10 questions

Rethinking equity investing at the National Bank of Austria post-2020

How can reserve managers escape low yields – and stay true to their mandate?

Reserve managers weigh the risks amid the Ukraine crisis

Appendix 1: Survey questionnaire

Appendix 2: Survey responses and comments

Appendix 3: Reserve statistics

Excitement has grown around central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) due to major developments in the currencies and payments world over the past two years. The topic has gained increased interest from governments, corporates, investors and anyone with an interest in payments or monetary policy. In recent months, more central banks have become involved in research projects, more answers are being found to the numerous design challenges, and more questions are coming our way on the subject. This chapter will look at key issues, short and long term, around the development, launch and impact of CBDCs around the world, by examining ten key questions (see Box 3.1, below). The subject is one that reserve managers will need to continue to learn about given some of the possible implications, and a final section focuses on this in particular.

Box 3.1 The key questions on CBDCs

-

-

Why are central banks looking more at CBDCs?

-

-

-

What is the difference between a CBDC and cryptocurrency?

-

-

-

What is the timeline around the world?

-

-

-

What design decisions do central banks need to make?

-

-

-

Will privacy be a major issue?

-

-

-

What is the latest with the PBoC’s digital currency?

-

-

-

What is happening in the developed world?

-

-

-

How is the FX market taking cryptocurrency developments?

-

-

-

Will CBDCs be used across borders?

-

-

-

What impact will CBDCs have?

-

The subject of CBDCs is constantly evolving. An increasing number of central banks have ramped up their efforts and more research papers have reached new conclusions. Work has also stepped up to explore how CBDCs could be used for cross-border transactions that could streamline international payments.

The impact on the global financial system could be huge, making findings that come from the leading pilots in China, Sweden and the Bahamas especially important. Plans by other central banks are eagerly awaited too – particularly from the Fed and the European Central Bank (ECB), whose thoughts are at a much earlier stage. The development of CBDCs could mean changes in the relative attractiveness of different currencies, it could lead to greater financial market efficiency and lower costs within payment networks.

Why are central banks looking more at CBDCs?

Central banks have been examining the need to provide a digital means of payment for a long time. The People’s Bank of China (PBoC) started its research in 2014 and Sweden’s Riksbank in 2016, and broader discussion of the topic has built momentum slowly since then. However, the past year or so has witnessed a sea-change in the way that many of the world’s biggest central banks view CBDCs, driven by the rise of private alternatives (cryptocurrencies and stablecoins) and the rapid decline in the usage of cash payments, a trend accelerated by the global pandemic.

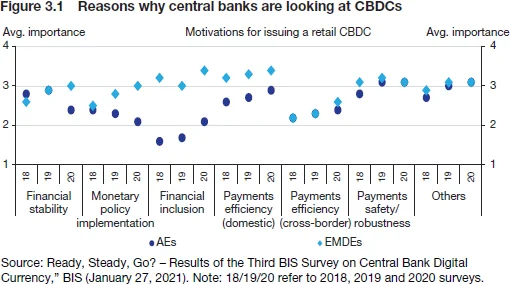

The underlying reasoning has varied by central bank. The most recent survey by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), from January 2021, showed that while some central banks have been thinking about CBDCs to ensure financial stability, many (particularly in the emerging world) have been investigating the benefits of raising financial inclusion. As Figure 3.1 demonstrates, improved payments efficiency or monetary policy tools have also been given as reasons by some central banks.

For households, using a CBDC may not involve any material changes in the way payments are done, but the improved security that can come with a more robust payments system should be a good reason to want to use them. However, this benefit (as well as lower costs of payments) may need to be communicated to encourage consumers to use this new means of payment instead of their existing alternatives.

What is the difference between a CBDC and cryptocurrency?

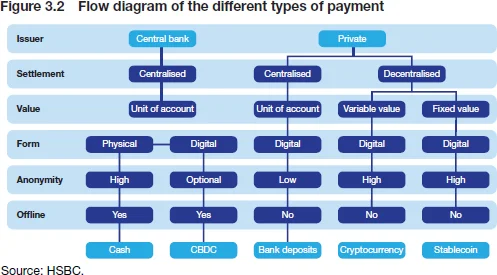

Central bank digital currencies have often been confused with cryptocurrencies, as both are new means of digital payment. In practice, that is where the similarities end. Figure 3.2 shows the difference between key payment methods – and while a cryptocurrency is a highly volatile instrument that does not function well as a means of payment (given the high transaction costs as well as the volatility), a CBDC should provide a stable, highly efficient means of payment. A CBDC is more akin to a central bank-backed stablecoin (a token with a fixed value) than a cryptocurrency.

Some of the confusion comes from the technology used. While a cryptocurrency uses blockchain technology (a type of distributed ledger technology, DLT), a CBDC doesn’t need to do so. Although most of the pilots across the world today use blockchain technology in one shape or form, it is not a necessary requirement for a CBDC since more traditional technology may suffice.

That distinction is important when thinking about some of the environmental concerns given the widely publicised energy costs associated with blockchain technology.11 Katie Martin and Billy Nauman, “Bitcoin’s Growing Energy Problem: ‘It’s a Dirty Currency’,” Financial Times (May 20, 2021). The idea of central banks (who are putting more emphasis on green issues) using an energy-sapping technology may seem odd, but even if a blockchain were to be used, it may not be decentralised to the same degree as a private cryptocurrency (or use a mining process), making it far less energy-intensive.

What is the timeline around the world?

A handful of CBDCs have already become available in the world. The first was the Bahamian sand dollar, a project launched in October 2020 that allows users to access the CBDC from a mobile app or a card, and which can be used at participating retailers. The sand dollar can be used widely, although a cap applies to some individual users, such as non-residents. CBDCs have also been introduced by the Central Bank of Nigeria, and the East Caribbean Central Bank has launched DCash, an electronic version of the Eastern Caribbean dollar. However, while these projects are interesting, the interest across the rest of the world remains relatively small.

The timeframes vary greatly. At the time of writing, China’s e-yuan is in a public trial phase, while Sweden’s Riksbank is in the second stage of its pilot. Progress has generally been faster in the emerging world. In Brazil, for instance, the central bank has said it expects the adoption of a digital real to be achieved in two or three years, while the Reserve Bank of India has stated it plans to issue a CBDC in the coming fiscal year, although the design of the CBDC is still to be decided upon.

Uruguay and Ecuador ran earlier pilots and are currently evaluating whether to move towards more widespread issuance. The Bank of Jamaica has successfully run a pilot and plans to release its CBDC in 2022, while in Ukraine additional pilots are scheduled to take place later this year.

In Asia, much work has gone into cross-border CBDCs and wholesale CBDCs, with partnerships between the central banks in Hong Kong, Singapore and Thailand.

In the developed world, where the top priority is “to do no harm”, progress has been slower and it is likely to stay that way, as central banks there prefer to err on the side of caution. The ECB’s report on its potential digital euro suggested that if the project was given the go-ahead, it would likely take another two or three years to develop, test and eventually roll out. Although this means a digital euro is unlikely before 2025, this could still put the ECB significantly ahead of many of its G10 peers. Nonetheless, the joint report from seven major central banks and the BIS from October 202022 BIS, “Central Bank Digital Currencies: Foundational Principles and Core Features” (October 9, 2020). highlighted that “authorities[…] need to be confident that issuance would not compromise monetary or financial stability, and that a CBDC could coexist with and complement existing forms of money, promoting innovation and efficiency.” As a result, progress in the developed world has been slower, but more central banks have been continually exploring their introduction.

What design decisions do central banks need to make?

Central banks engaged in pilots and research are now faced with numerous important decisions. Some of these centre on the design of a CBDC from a technical perspective – what underlying technology to use, whether a CBDC should be “direct” (where the relationship of users is with the central bank) or “indirect” (where the CBDC is distributed via the banking system), and whether it should be usable across borders.

Some of the big questions central banks need to resolve include:

-

-

Direct or indirect (indirect seems more likely)?

-

-

-

Which technology should be used (eg, blockchain)?

-

-

-

How anonymous should the CBDC be (to be decided on a case-by-case basis)?

-

-

-

Limits or caps (the latter seems unlikely)?

-

-

-

Interest bearing or not interest bearing (most pilots are not)?

-

Most research seems to suggest that an indirect model will be used, since a direct model carries too many financial stability risks and means that central banks would have to be responsible for onboarding and management of accounts, something they are not easily equipped to do.

Beyond that, there is a question about whether a CBDC should, or will, be interest bearing. To date, pilots seem to be erring towards non-interest bearing CBDCs (which could make a negative interest rates policy almost impossible in practice; the second stage of the Riksbank’s pilot, for instance, has been exploring this in more detail).33 See Riksbank, “A Solution for the e-Krona Based on Blockchain Technology has been Tested,” press release (April 6, 2021). Other CBDCs, such as China’s e-yuan, will probably not charge or pay interest, at least initially. Hence, it may affect the incentives for using/owning physical cash, which also does not pay interest, but it should have limited immediate implications for bank deposits as well as other remunerating assets.

Will privacy be a major issue?

Privacy concerns have frequently been raised when discussing CBDCs. As the BIS 2021 annual report highlighted, central banks will have to decide how anonymous transactions will be within their CBDC system.

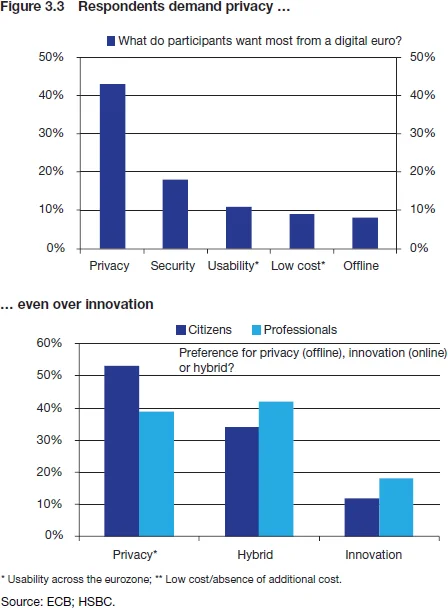

For the ECB, its public consultation found that privacy was one of the top priorities for end users – as citizens prefer privacy over innovation when it comes to what they would like to see from a digital euro (see Figure 3.3).

Essentially, central banks will be faced with a choice, ranging from having almost completely anonymous payments to having an incredible amount of detail on every transaction in the economy. While completely anonymous payments may seem like a good thing for many consumers, they could allow a degree of illicit activity even more easily than cash does today. For central banks, that may not be something they would feel comfortable with.

Equally, although many may not be comfortable with central banks knowing everything they do on a day-to-day basis, that aggregated data could allow central banks and governments to set better policy in real time. A balance will have to be struck, and where different central banks sit on that spectrum will be a choice that will need to be carefully considered.

Therefore, as part of the design process, there is an important question over whether a CBDC should be a token (where the unit is verified) or an account (where the user is verified). The BIS 2021 annual report considered the merits of both options, and suggested that an account-based system would be better, based mainly on its improved properties as a store of value in terms of security, the ability to tier interest rates depending on ownership and the level of anonymity. If a token architecture is chosen, then there is the ability to have anonymous payments – but if an account is chosen, the spectrum is much smaller, as payments have to be verified against a given user, so full anonymity is not possible.

What is the latest with the PBoC’s digital currency?

China’s digital currency – known as the “e-yuan” – has made quick progress over the past two years. By the end of 2021, the e-yuan had been tested in over eight million pilot scenarios. A total of 261 million individual wallets have been opened and the transaction amount has reached 88 billion yuan. As recently as mid-2021, there were only 24 million individual and corporate users, and the transaction amount only totalled 34.5 billion yuan.

| CBDC | ||||

| Cash | Token | Account | Commercial bank deposits (current account) | |

| Claim structure | Claim on central bank | Claim on central bank | Claim on a bank | |

| Risks | Loss, theft and fraud | Loss, theft, fraud, cyber risk | Fraud, cyber risk | Fraud, cyber risk, illiquidity and insolvency |

| Backstop | Full | Full | Full | Deposit insurance |

| Anonymous holdings?* | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Interest rate | No | Can be set by central bank | Set by banks, market based | |

| Interest rate tiering? | No | No | Yes | Set by banks |

| Caps on holdings | No | No | Yes | Generally, no |

| Source: BIS, “Annual Report 2021”. Note: is it possible to have fully anonymous holdings? |

||||

Over the past year, the PBoC successfully carried out e-yuan pilot tests in a number of cities in mainland China via lotteries and salary payments. The trial operation was expanded from small-scale, closed-loop testing to large-scale, open testing and more. In October 2020, there was a trial in the Luohu district in Shenzhen with 50,000 residents, which was expanded in April 2021 to 500,000. The Beijing Winter Olympics was another major testing ground for the e-yuan, with consumers using it for transportation, dining and accommodation, shopping, tourism, healthcare, telecommunication and entertainment. Foreigners also participated in the pilot test as the Bank of China demonstrated a machine that converts foreign currencies into e-yuan. Users needed to link their passports to the transaction, but did not require a bank account. The total amount of the e-yuan payments in the Beijing National Stadium surpassed that of Visa at the opening ceremony of the Winter Olympics.44 Digital yuan transactions beat out Visa at Winter Olympics venue: Report, Coin Telegraph, 10 February 2022.

Design issues

On November 9, 2021, the PBoC’s governor Yi Gang mentioned that the e-yuan would follow the principle of “anonymous for small-value and traceable for large value transactions.” Information will be collected using the principle of “minimum and necessary,” which is less than collected by the existing electronic payment instruments. Under this principle, the e-yuan operators can open four types of e-wallets for customers according to the information they supply. The e-wallets with the least privileges only require a phone number and will be anonymous even to the PBoC. Daily transaction value for this type of e-wallet holder will be capped at 5,000 yuan, with an annual cap of 50,000 yuan. The highest privileged e-wallet needs to be opened at a bank counter with personal identification, and has no transaction cap.

The PBoC is also testing the programmability of the e-yuan (see Table 3.2). According to a news report, in 2021 there was a trial of the e-yuan in Chengdu that was pre-programmed to link with public transportation for 100,000 residents.55 China’s new digital yuan test shows it can be programed to like with public transportation, The Block (July 2, 2021). More recently, China’s first e-yuan smart contract that enables settlements for photovoltaic services was put into practice in Xiong’an.66 The first order of digital RMB smart contract enabled photovoltaic settlement, People.cn (January 6, 2022).

Developments in 2021

We believe that the PBoC will steadily promote the pilot tests of the e-yuan and further broaden its usage in retail transactions, government services and other scenarios. For example, Beijing has been looking into setting up a digital asset exchange as the government promotes the usage of the e-yuan.77 Beijing looks into setting up digital asset exchange to push the e-yuan, South China Morning Post, 26 November 2021.

Cross-border testing of the e-yuan has become another key area of focus. According to a Hong Kong official blog,88 Paul Chan Mo-po, “Staying Abreast with the Times and Keeping our Mission Firmly in Mind,” blog (June 27, 2021). it will collaborate with the PBoC to test the e-yuan in Hong Kong. The director-general of the Digital Currency Institute at the PBoC, Mu Changchun, also mentioned that the PBoC has been exploring connecting the e-yuan with the Faster Payment System in Hong Kong, meaning that the e-yuan and the Hong Kong dollar will be fully convertible.99 China’s PBOC wants to link e-CNY with Hong Kong’s Faster Payment System, YiCai (December 9, 2021).

The other development to watch is the cross-border trial between the PBoC, the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA), Bank of Thailand and the Central Bank of the United Arab Emirates under the m-CBDC Bridge Project, which aims to tackle the problems of cross-border transfers – such as inefficiencies, high costs, low transparency and regulatory challenges. According to its latest release,1010 Hong Kong FinTech Week 2021, HKMA (November 3, 2021). a total of 22 private sector participants from these four jurisdictions have identified 15 potential business use cases, including international trade settlement, interoperability with digital trade finance platforms, and foreign exchange (FX) transactions.

| By degree of strength of customer information identification | By type of holder | By type of carrier | By type of authorisation |

| Authorised operators assign different types of digital wallets to customers based on the strength of their personal identification information and set per-transaction and daily limits, as well as maximum balances according to the strength of real name information. | Individual e-wallets (个人钱包) – for natural persons and self-employed individuals | Software e-wallet ( 软钱包) – provides services through mobile payment apps, software development kits (SDKs) and application programming interfaces (APIs) | Main e-wallet (主钱包) – the e-wallet holder can set the main e-wallet as the parent e-wallet and open several sub-wallets under the main e-wallet |

| The least-privileged e-wallets can be opened without providing identities to reflect the principle of anonymity. Users can open least-privileged anonymous e-wallets by default and upgrade them to higher level real name ones as needed. | Corporate e-wallets (对公钱包) – for legal persons and unincorporated institutions | Hardware e-wallet (硬钱包) - supported by IC card, mobile phones, wearable objects and internet devices | Sub-wallets (子钱包) – individuals are able to set payment caps, payment conditions, personal privacy protection and other functions through sub-wallets; enterprises and institutions are able to pool and distribute funds and manage finances through sub-wallets |

| Source: PBoC; HSBC. | |||

What is happening in the developed world?

While the PBoC is leading the charge among the world’s biggest central banks, things have been much slower for its developed world counterparts. In the US, for instance, there have been a wide range of views from Federal Reserve governors. After a lengthy delay, the Fed released a paper1111 Money and Payments: The US Dollar in the Age of Digital Transformation, 14 January 2022. outlining how it sees the advantages and disadvantages of CBDCs, and especially the need for a digital US dollar. Similar to other central banks, the Fed aims to foster public dialogue and seeks feedback by 20 May 2022 to establish whether to proceed or not, alongside approval from the US executive branch and Congress. In this latest document, the Fed does not make a specific recommendation, but the inception of a digital dollar still appears a long way off.

In terms of the dollar’s role in the world, if other countries move ahead with their CBDC development and those CBDCs prove to be more attractive than the existing forms of the US dollar, its share in international transactions could decline. As a result, the Fed believes a digital dollar could support its global status.

The ECB has been a little more proactive. It decided to progress with a formal investigation of a digital euro in July 2021. The project started in October 2021, and will involve a two-year investigative phase that aims to develop at least one design that meets the requirements of the public. Following this, the decision on whether to develop a digital euro will be made.

The Bank of England has also stepped up its level of research, having established its CBDC Taskforce in April 2021. In addition, the central bank has set up a CBDC unit that will work on answering the many CBDC design issues from the UK’s perspective. The first consultation paper1212 Bank of England publishes Discussion Paper on New Forms of Digital Money and summarises responses to the 2020 Discussion Paper on Central Bank Digital Currency, Bank of England, 7 June 2021. from the Bank of England suggested there are five key issues here: financial inclusion; a competitive CBDC ecosystem; whether non-CBDC payment innovations could deliver the same benefits; protecting users’ privacy; and that a CBDC should “do no harm” to the Bank’s ability to meet monetary and financial stability objectives. Norges Bank has started its own initiative in a similar vein, while the Bank of Canada sees a CBDC as a contingency, and is undergoing work to be able to release one should the need arise.

However, in the developed world Sweden’s Riksbank is a long way out in front. The e-krona project is now four years old and in the second stage of its pilot. The lessons that come from the project could well be key for other developed market central banks facing the same questions around their own CBDC design. The Riksbank has yet to fully decide whether it will issue an e-krona, with Governor Stefan Ingves1313 Riksbank Says Sweden Could Have a Digital Central Bank Currency in 5 Years: Report, Coindesk, 16 April 2021. saying in April 2021 that five years “is a reasonable target” for an operational digital currency, but should the latest stage of the pilot go to plan it could be introduced more quickly.

How is the FX market taking cryptocurrency developments?

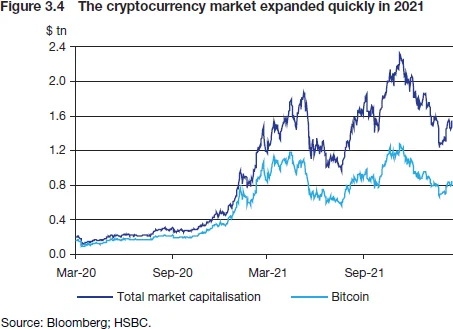

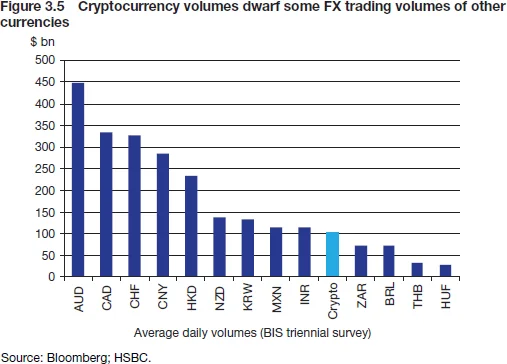

The cryptocurrency market expanded sharply between March 2020 and May 2021, with the total market capitalisation of the ten largest cryptocurrencies rising nearly ten times (see Figure 3.4). Since then, things have slowed. Perhaps it is unsurprising that cryptocurrency volumes dwarf some emerging market currencies when compared to the FX volume data from the BIS (see Figure 3.5). However, in certain periods cryptocurrency volumes even climbed above $250 billion per day, which exceeded the average daily turnover of some Asian currencies (such as the Hong Kong dollar).1414 Triennial Central Bank Survey of Foreign Exchange and Over-the-counter (OTC) Derivatives Markets in 2019, BIS, 8 December 2019. With such vast transactions, it is not difficult to imagine possible spill-over effects of cryptocurrencies into other markets.

Due to the sheer number of cryptocurrencies, it is difficult to account for them all in our comparison with other instruments. Given the large presence of Bitcoin in the cryptocurrency market, however, its volatility can cause a ripple effect to other cryptocurrencies and other instruments. Nevertheless, the relationships between cryptocurrencies and exchange rates are not stable, but are generally weak and inconsistent. One possible reason for this could be the high volatility of cryptocurrencies, which adds a sizeable amount of noise in any analysis.

For a more substantial relationship to develop between cryptocurrencies and FX, the former will probably need to change on a number of fronts, not least via an increase in the level of institutionalisation in cryptocurrencies and deeper market infrastructure. If this happens, we may see evidence of stronger relationships emerging. For now, however, there is little to suggest that these crossovers can be used to make better investment decisions or trade exchange rates based on how cryptocurrencies are performing.

Will CBDCs be used across borders?

It is clear that there is some motivation to allow CBDCs to be used for cross-border purposes. For instance, the ECB said1515 The international role of the euro, ECB, June 2021. in October 2021 that the digital euro “should potentially be accessible outside of the euro area... in a way that is consistent with the objectives of the Eurosystem and convenient to non-euro area residents.” Otherwise, they added, the international role of the euro could weaken at the expense of other CBDCs. Of course, strengthening euro internationalisation is an official policy of EU institutions, and a digital currency appears to be part of this strategy.

Revolutionising cross-border settlements can also benefit the PBoC’s long-term goal of renminbi internationalisation. Many non-US entities trade with Chinese entities, but a large portion of their cross-border transactions use the US dollar as a vehicle currency in part because of the correspondent banking model. However, if cost-efficient, peer-to-peer transfers become more common in cross-border transactions (replacing correspondent banking), entities would be able to directly exchange renminbi for foreign currencies without involving the dollar.

There is also a more direct motivation to implement a cross-border CBDC, which comes down to lowering transaction costs and improving efficiencies. After all, most cross-border payments take place via a correspondent banking model1616 Most payments systems are domestic in scope, operate in a single currency and have high barriers of entry (limited eligible participants). Correspondent banks are basically the linkages between payment systems. Consider a cross-border transaction between A and B. A domestic bank in country A may not be a participant in the settlement system of country B, and vice versa, and so the banks have to look for a correspondent bank C that has settlement accounts in both A and B. Often, this process involves not just one correspondent bank C, but many intermediaries in different jurisdictions. despite it being regarded as expensive and inefficient.1717 See Bank of Canada, Bank of England and the Monetary Authority of Singapore, “Cross-border Interbank Payments and Settlement: Emerging Opportunities for Digital Transformation” (November 2018). There are various reasons for this,1818 See Morten Linnemann Bech and Jenny Hancock, “Innovations in Payments,” BIS Quarterly Review (March 1, 2020) and Tara Rice, Goetz von Peter and Codruta Boar, “On the Global Retreat of Correspondent Banks,” BIS Quarterly Review (March 1, 2020). including:

-

-

a declining number of correspondent banks (which means there will be even more intermediaries involved, thereby lengthening the payment chain);

-

-

-

high costs of compliance with various regulations (anti-money laundering, counter terrorist financing, know your customer, etc) that could differ across borders;

-

-

-

lack of interoperability across payments systems of different economies (because of different technical standards, operational standards, operational hours, etc);

-

-

-

the growing size of the FX market could create settlement risks.

-

Central bank digital currencies could address these topics. The process of launching a digital currency will lead a central bank to rethink, redesign and upgrade many aspects of its settlement system and regulatory framework. In particular, incorporating DLT solutions in a settlement system could allow for peer-to-peer transfers, smart contracts, automatic processing, real-time 24/7 access – features that would significantly improve cross-border payment efficiency once more settlement systems in other countries also use DLT solutions.1919 See Bank of Canada and the Monetary Authority of Singapore, “Enabling Cross-border High Value Transfer Using Distributed Ledger Technologies,” Jasper–Ubin Design Paper (May 2, 2019), and Bank of Thailand and the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, “Inthanon-LionRock: Leveraging Distributed Ledger Technology to Increase Efficiency in Cross-border Payments” (January 22, 2020).

Moreover, as many central banks are simultaneously studying CBDC, there could be an opportunity for international coordination from a clean-slate perspective – with the common goal of achieving interoperability across modernised settlement systems. International cooperation would generally benefit from leadership. However, this is not straightforward as it would require substantial coordination among central banks via their legal, regulatory and technology frameworks. The BIS also correctly pointed out that: “central banks will need to evaluate whether they are willing to relinquish some system control and monitoring functions to an operator, for which the governance arrangements would need to be (jointly) agreed. Negotiating these trade-offs across multiple central banks will be a challenge.”2020 The changing retail payments landscape, Kansas City Fed, November 9–10, 2009.

Despite these long-term uncertainties, cross-border trials have already begun. The collaboration between the Hong Kong Monetary Authority and Bank of Thailand with the Inthanon-LionRock project has helped to identify some of the hurdles when testing a shared “corridor” network. Also, the Multiple CBCD (mCBDC) Bridge initiative, which has seen the HKMA, PBoC, Bank of Thailand and the Central Bank of the UAE working in cooperation, is aimed at further investigating and developing a proof of concept (PoC) to facilitate real-time FX transactions across borders.

What impact will CBDCs have?

The impact of the launch of CBDCs will largely depend on both the design decisions that are made and how widely used they are. One of the biggest challenges could be to get households and businesses to use CBDCs over other forms of payment, and so the benefits to consumers may have to be outlined to encourage usage. Below, we consider four channels of influence by way of a conclusion.

Payments efficiency: One of the clearest impacts of a CBDC is in improving payments efficiency and cutting payment costs. While many individuals may not notice a huge change in their day-to-day usage of electronic payments, this improved infrastructure could cut transaction costs for businesses – which could be passed on or such costs could be used more effectively. A paper from the Kansas City Fed2121 Fumiko Hayashi and William R. Keeton, “Measuring the Costs of Retail Payment Methods,” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City (2012). has suggested that retail payment costs are estimated to absorb 0.5–0.9% of annual economic output in many countries. This does not just provide an efficiency gain directly, but could unlock those funds to be spent on more productive endeavours by firms, possibly supporting investment or hiring.

Security: CBDCs could allow for more secure payments, as well as removing some of the insolvency and illiquidity risks that come with the widespread usage of private forms of digital money.

Financial inclusion: Cheaper digital payments could encourage more widespread adoption of CBDCs in the emerging world, allowing more people access to digital forms of money and helping to improve financial inclusion and growth. The same could also be true in the developed world, where there are still some people either unbanked or underbanked, and CBDCs could be designed to alleviate the reasons for this.

Programmable money: One impact that has gathered more attention is the ability to have programmable money – ie, funds that can only be used within certain timeframes or for purchasing certain items. This idea has gained prominence during the pandemic due to the nature of stimulus being provided: if direct payments could only be used for food or housing, or were time-sensitive (and thus could not just be added to savings), this could be a very powerful stimulus tool. However, others are more sceptical, believing that such control over what people do with their money could be very harmful and lead to too much state control.

The Bank of England deputy governor Sir Jon Cunliffe gave one example of this, highlighting that a digital pound would allow parents to programme their children’s pocket money so that they are unable to buy sweets,2222 Eva Szalay, Colby Smith and Thomas Hale, “The End of Privacy? Central Banks Plan to Launch Digital Coins,” Financial Times (June 14, 2021). causing concern among some that this would be too big a step.

However, given that CBDCs will co-exist with cash and other forms of payment for some time to come, these impacts may be more of a slower burn than instantaneous, particularly as usage may start out only in a very limited way.

Reserves: The role of the US dollar as the world’s reserve currency could be impacted if other countries move ahead with their CBDC development and those CBDCs prove to be more attractive than the existing forms of the dollar. As a result, the share of the dollar in international transactions could decline. Therefore, the Fed believes a digital dollar could support the dollar’s global status and with the recent executive order from President Biden for the Treasury Department, the Commerce Department and other key agencies to prepare reports on “the future of money”, progress on that path may have started. For now, the US remains a long way behind some other central banks, but developments will be worth tracking.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.centralbanking.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com