The cashless society?

James Pomeroy

The cashless society?

Foreword

The cashless society?

Executive summary

Trends in reserve management: 2019 survey results

Implementing a corporate bond portfolio: lessons learned at the NBP

Sovereigns and ESG: Is there value in virtue?

A methodology to measure and monitor liquidity risk in foreign reserves portfolios

Reserve management: A governor’s eye view

How Singapore manages its reserves

Appendix 1: Survey questionnaire

Appendix 2: Survey responses and comments

Appendix 3: Reserve statistics

The world is steadily giving up on cash. Think about your own spending habits: how often do you use paper money nowadays compared to a few years ago? The notes in your wallet will have been replaced by cards and mobile payments – and the cheques that used to be there have long gone. Even in countries where cash usage is still rising, mainly in Latin America, the growth is electronic payments has been even faster. Cash’s share of transactions globally is waning.

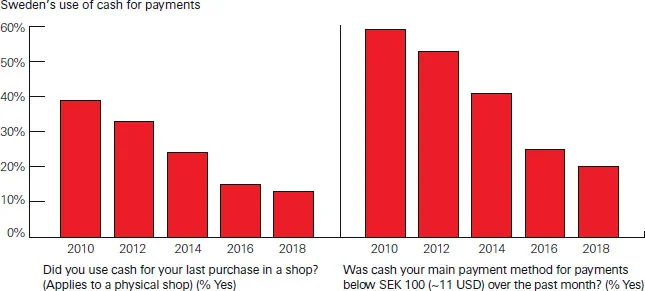

This shift has been driven by a number of factors: in many countries the key has been the new technologies that make these payments possible, as well as the willingness of populations to adopt them. Across northern Europe cash payments are in freefall. Now only 12% of transactions in Sweden are estimated to be made with cash and even with small payments (< SEK100/USD11) only 20% are being made with cash. The move has gone so far that churches and the homeless take cash-free donations while many coffee shops, bars and museums across the country will no longer accept notes or coins as payment.

Sweden’s cash usage has declined sharply

But it’s not just in this tech-savvy part of the world where these shifts are happening. In Korea, government policy is helping the shift by phasing out small coins. In Kenya and other parts of sub-Saharan Africa it is mobile money, supported by a rapid uptake of mobile phones, which is helping the economy to shift away from cash. In China, social networks and associated payments through the likes of AliPay have created the largest mobile payments market in the world: more than fifty times the size of the US equivalent. A high-profile move has been in India, where Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s demonetization policy in November 2016, aimed at removing certain large bills from circulation, has led to a sharp uptake in mobile payments, with PayTM a notable player.

What does this mean?

From an economist’s perspective, cash has few advantages. It creates friction in the economy that makes things more expensive and time-consuming: getting cash from ATMs, counting takings in a shop and transporting it to the bank. It also facilitates crime, ranging from theft to narcotics trade to tax evasion and corruption. Moreover, businesses all over the world will save money on cash storage and security while consumers will benefit from lower costs as a result of these savings.

Governments in the emerging world could have the most to gain by cutting the amount of cash circulating in their economies: these are sometimes countries where the shadow economy is larger and corruption is usually more endemic. And across emerging markets, the advent of mobile money is allowing millions of people to enter the banking system for the first time – giving them access to credit, savings and mortgages that wasn’t possible before. This could provide a huge lift to growth prospects.

Various estimates for the size of the shadow economy

| Area | Estimate (% GDP) | |

| OECD (2015) | 18.0 | Friedrich Schneider |

| OECD (2007) | 16.1 | Friedrich Schneider & Colin Williams |

| Developing (1988-2000) | 35-44 | Friedrich Schneider & Dominik Enste |

| Transition (1988-2000) | 21-30 | Friedrich Schneider & Dominik Enste |

| OECD (1988-2000) | 14-16 | Friedrich Schneider & Dominik Enste |

| Developed (2002-2003) | 13.0 | Friedrich Schneider |

| Developing (2002-2003) | 36.0 | Friedrich Schneider |

| Source: Friedrich Schneider, papers available at: http://www.econ.jku.at/members/Schneider/files/publications/2015/ShadEcEurope31.pdf,https://iea.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/IEA%20Shadow%20Economy%20web%20rev%207.6.13.pdf, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/issues/issues30/ & https://www.stlouisfed.org/publications/regional-economist/january-2015/underground-economy | ||

Is it all good news?

The move away from cash isn’t welcomed by everyone. Older generations (who are the heaviest cash users) don’t like the speed at which this is happening: particularly with stores starting to turn cash away. In Sweden, 62% of 65-84 year olds who expressed an opinion were negative on the move away from cash. This compares to just 18% of 18-24 year olds.

A possibly even bigger challenge is cybercrime, which has been on the rise as online activity has increased. Data from Javelin Strategy & Research, showcased in the Wall Street Journal, suggests that 16.7m Americans were victims of fraud in 2017, up from 12.6m in 2012, coinciding with a greater online threat. Technology is helping to overcome these challenges, with better algorithms to spot money laundering and greater security measures to prevent hacking.

So what now?

Central banks now face a challenge. As cash becomes less of a universally accepted and accessible means of payment, what should they do? According to the BIS, 70% of central banks globally are exploring the idea of issuing their own digital currency, aimed at providing the same properties as cash, but in electronic form. The rationale for doing so varies by country, but a BIS survey suggests that most developed market central banks are concerned by financial stability and payment safety, whereas in emerging markets the priority is financial inclusion.

The exact form that this money should take is the cause of much of this research: should a central bank digital currency (CBDC) use a token or account system? A ‘token’ system, which could use blockchain technology akin to that which Bitcoin uses, would allow central banks to design a form of money that has all of the features of cash but is electronic. And it could provide the option of paying interest should a central bank decide that it is useful. An ‘account’ system would work with a mobile app and be more akin to a commercial bank account today. This account-based system would be like having a bank account at the central bank, available to the general public.

Different possibilities for central bank money

| Existing central bank money | Central bank digital currencies | ||||

| Cash | Reserves and settlement balances | General purpose | Wholesale only token | ||

| Token | Account | ||||

| 24/7 availability | ✔ | ✘ | ✔ | (✔) | (✔) |

| Anonymity vis-á-vis central bank | ✔ | ✘ | (✔) | ✘ | (✔) |

| Peer-to-peer transfer | ✔ | ✘ | (✔) | ✘ | (✔) |

| Interest-bearing | ✘ | (✔) | (✔) | (✔) | (✔) |

| Limits or caps | ✘ | ✘ | (✔) | (✔) | (✔) |

If such a product was possible, it could have wide-ranging implications for the economy. Clearly the role of a central bank would be quite different, as would the role of monetary policy. The BIS suggests that a CBDC would enrich the options available to a central bank, meaning that the pass-through from interest rate setting could be more effective (as it would apply directly to the population) as well as giving greater ability to pursue negative interest rates should that be necessary.

There could of course be implications for commercial banks which rely on the deposits of consumers. Given the alternative of a CBDC, the need to hold an account with a commercial bank is reduced; as well as making it far easier for any funds to disappear from commercial banks to the central bank in a time of stress. This could pose financial stability concerns, but many argue that this would be more favourable than money leaving the financial system entirely, into notes, gold or other physical assets.

Cash to continue for now

Given the work that needs to be done to explore how feasible a CDBC could be, a fully-functional example may be some way off. Equally, while many parts of the population don’t want to see cash disappear, it may be hard for governments to promote such a position and policy may have to lean against the societal shift to keep cash in circulation. For the time being we are still in a ‘less-cash’ world rather than a cashless one, but the benefits for businesses, consumers and governments should gradually become clearer.

James Pomeroy,

Associate Director, Global Research, HSBC

Different possibilities for central bank money

| Existing central bank money | Central bank digital currencies | ||||

| Cash | Reserves and settlement balances | General purpose | Wholesale only token | ||

| Token | Account | ||||

| 24/7 availability | ✔ | ✘ | ✔ | (✔) | (✔) |

| Anonymity vis-á-vis central bank | ✔ | ✘ | (✔) | ✘ | (✔) |

| Peer-to-peer transfer | ✔ | ✘ | (✔) | ✘ | (✔) |

| Interest-bearing | ✘ | (✔) | (✔) | (✔) | (✔) |

| Limits or caps | ✘ | ✘ | (✔) | (✔) | (✔) |

If such a product was possible, it could have wide-ranging implications for the economy. Clearly the role of a central bank would be quite different, as would the role of monetary policy. The BIS suggests that a CBDC would enrich the options available to a central bank, meaning that the pass-through from interest rate setting could be more effective (as it would apply directly to the population) as well as giving greater ability to pursue negative interest rates should that be necessary.

There could of course be implications for commercial banks which rely on the deposits of consumers. Given the alternative of a CBDC, the need to hold an account with a commercial bank is reduced; as well as making it far easier for any funds to disappear from commercial banks to the central bank in a time of stress. This could pose financial stability concerns, but many argue that this would be more favourable than money leaving the financial system entirely, into notes, gold or other physical assets.

Cash to continue for now

Given the work that needs to be done to explore how feasible a CDBC could be, a fully-functional example may be some way off. Equally, while many parts of the population don’t want to see cash disappear, it may be hard for governments to promote such a position and policy may have to lean against the societal shift to keep cash in circulation. For the time being we are still in a ‘less-cash’ world rather than a cashless one, but the benefits for businesses, consumers and governments should gradually become clearer.

James Pomeroy,

Associate Director, Global Research, HSBC

About HSBC Global Banking and Markets

The key to lasting success is not simply gaining a competitive edge but maintaining it over the long term. Establishing the foundations for global growth requires a business strategy based on local knowledge and insight, aligned to a global outlook. To do that, you need the strength of a network that offers strong ontheground relationships, supported by broad global expertise. These are the dynamics that we believe can drive the future of your business, and HSBC Global Banking and Markets is focused on helping you build success that stands the test of time.

Global Scale:

In this increasingly interconnected world, ideas and capital are flowing around the globe, driving growth and disrupting the status quo. New trade routes emerge, propelling emerging economies to the spotlight and creating opportunities for companies and financial institutions worldwide. Our Global Banking and Markets business is globally connected with a strong footprint in many of the World’s key regions both in the developed and emerging markets.

Innovation:

Our Central Banking and Reserve Management team comprises experienced bankers and product specialists, each chosen for their specific expertise and knowledge of the global financial markets. They work closely with a broad and diverse range of reserve managers, across the globe, to understand their needs and deliver integrated, customised banking propositions. We provide a full range of products and services to central banks globally, including fixed income, foreign exchange, equities, precious metals, asset management, custodial services and payments & cash management.

Long-term commitment:

Our aim is to partner with our clients to help them achieve consistent, long-term performance while delivering commercial opportunities and solutions in both developing and developed markets.

Contacts:

EMEA :

Name: Bernard Altschuler

Email: bernard.altschuler@hsbc.com

Phone: +44 (0)20 7992 2330

Name: Tom Wright

Email: tom1.wright@hsbc.com

Phone: +44 (0)20 7005 8664

Americas :

Name: Elissar E Boujaoude

Email: elissar.e.boujaoude@us.hsbc.com

Phone: +1 212 525 3017

Asia Pacific:

Name: Charlotte Kirkcaldie

Email: charlotte.kirkcaldie@hsbc.com.hk

Phone: +852 28222403

Name: Witanya Singkanjanawongsa

Email: witanya.singkanjanawongsa@hsbc.com.sg

Phone: +852 28222403

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.centralbanking.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com