Will the dollar remain the world’s reserve currency?

Executive summary

Trends in reserve management: 2023 survey results

The role of gold in central bank reserves

Will the dollar remain the world’s reserve currency?

Interview: Golan Benita

Reserve management at the BCB

NDF interventions in Latin America

Appendix 1: Survey questionnaire

Appendix 2: Survey responses and comments

Appendix 3: Reserve statistics

The US and other developed nations imposed a set of sweeping financial sanctions on the Russian economy following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. These effectively froze around 50% of the country’s $630 billion international reserves portfolio. Additionally, it prevented some of the country’s banks from using global financing messaging system Swift. International assets of leading businessmen and officials close to the Kremlin were also seized. In this way, the so-called weaponisation of the dollar served to blatantly use the greenback’s global reserve currency as a foreign policy tool, inflicting an immediate shock to the ruble’s exchange rate.

The Bank of Russia’s governor, Elvira Nabiullina, acknowledged that “the conditions for the Russian economy have altered dramatically”. In a press conference on February 28, 2022, she said: “The new sanctions imposed by foreign states have entailed a considerable increase in the ruble exchange rate and limited the opportunities for Russia to use its gold and foreign currency reserves.” Then, in March, Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov pointed out that no-one assessing possible western sanctions could have predicted the crippling measures the US, the European Union, UK, Canada and Japan, resorted to. “It was simply theft,” Lavrov declared.

Most tellingly, the speaker of the Russian lower house of parliament, Vyacheslav Volodin, predicted these actions would alter the current international monetary system. “This is the beginning of the end of the dollar’s monopoly in the world,” he declared. “Anyone who keeps money in dollars today can no longer be sure that the US will not steal their money.”

This claim resonates with regimes that suffered (or still suffer) under similar sanctions in the past. These include countries such as Iran, Syria and Venezuela. But it has also triggered debates about whether emerging nations should divest away from the US dollar and other western assets, and increase their exposure to alternatives, with the Chinese renminbi being the most obvious option.

This had been part of the strategy that the Bank of Russia followed in a bid to limit the impact of US sanctions imposed after Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea and the occupation of Ukraine’s eastern region of Donbass by Russian-backed separatists. Russia progressively reduced its US Treasury holdings from $164.4 billion in January 2013 to virtually 0 in January 2023. This diversification away from the dollar accelerated in the two years prior to the 2022 invasion. According to the Bank of Russia’s foreign exchange and gold asset management report, dollar-denominated assets declined from 22.2% of the foreign exchange assets in June 2020 to 16.4% in June 2021. Over the same period, renminbi holdings increased from 12.2% to 13.1%, although gold declined from 22.9% to 21.7%. In 2020–21, the Russian central bank reinforced the role of the euro as its main reserve currency, likely expecting gas-dependent Europe to be more reluctant to follow any US lead on sanctions. It increased its allocations from 29.5% to 32.3%.

“Reserves management has been used as a weapon. That is undeniable,” says the head of reserves of a major emerging market central bank. Nonetheless, the official points out that context matters: “You have to ask yourself the reason why they are using reserves as a weapon: was it warranted or not?” He adds that if a central bank concludes it needs to reallocate its reserves to avoid the Bank of Russia’s fate, then this central bank would need to answer another set of questions: “‘Where am I going to go?’ If the answer is the renminbi as a way of avoiding the wider western alliance, ‘am I certain that China is not going to use my RMB holdings as a weapon against me for geopolitical reasons in the future?’ I’m not entirely sure.”

Geopolitical factors

Regardless of the position that central banks adopt on reserve currency allocations, the US and its allies’ response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine has added a new set of policy and investment risks for reserve managers to ponder in their strategic asset allocations. “Central banks will need to take into account geopolitical risk, which I don’t think was a consideration at all up until now,” says Isabelle Mateos y Lago, global head of BlackRock’s official institutions group. “Whether you like it or not, this is something that you cannot ignore.”

In fact, the HSBC Reserve Management Trends (RMT) Survey 2023 found that more than 16% of central banks identify geopolitical tensions as the most significant risk facing their reserve managers.

“It seems geopolitical risks weigh more and more on the markets and have a stronger spillover effect,” says one central bank respondent from Europe.

“The escalation of geopolitical tensions could have far-reaching consequences – for instance, triggering new supply chains disruptions, the deterioration of the global economic outlook, capital outflows from emerging markets and increased volatility,” points out another central bank in the same region.

Another European central bank shares this perspective, adding: “Geopolitical tensions and above-target inflation recently started to move closely together, and we expect this trend to continue in the future.”

Regarding the willingness to actively move away from the status quo, Mateos y Lago identifies two broad groups of countries. One is closely aligned with the US economically, financially, politically and militarily. In these jurisdictions, China’s renminbi is not only ruled out as a global alternative to the dollar, but potentially seen as the next Russia, the object of future sanctions. “In these countries, I haven’t heard anybody saying they’re going to get rid of their existing renminbi exposures, but they’re certainly putting on hold any plans to ramp up this exposure,” she says. An example of where this is taking place is the Czech National Bank.

But beyond core members of the sanctioning alliance, reserve managers worldwide “see a need to diversify the geopolitical risk”, points out Mateos y Lago: “What we’ve heard from them is that their plans don’t change – essentially, they’re going to stay on the path of ramping up their exposure to Chinese assets.”

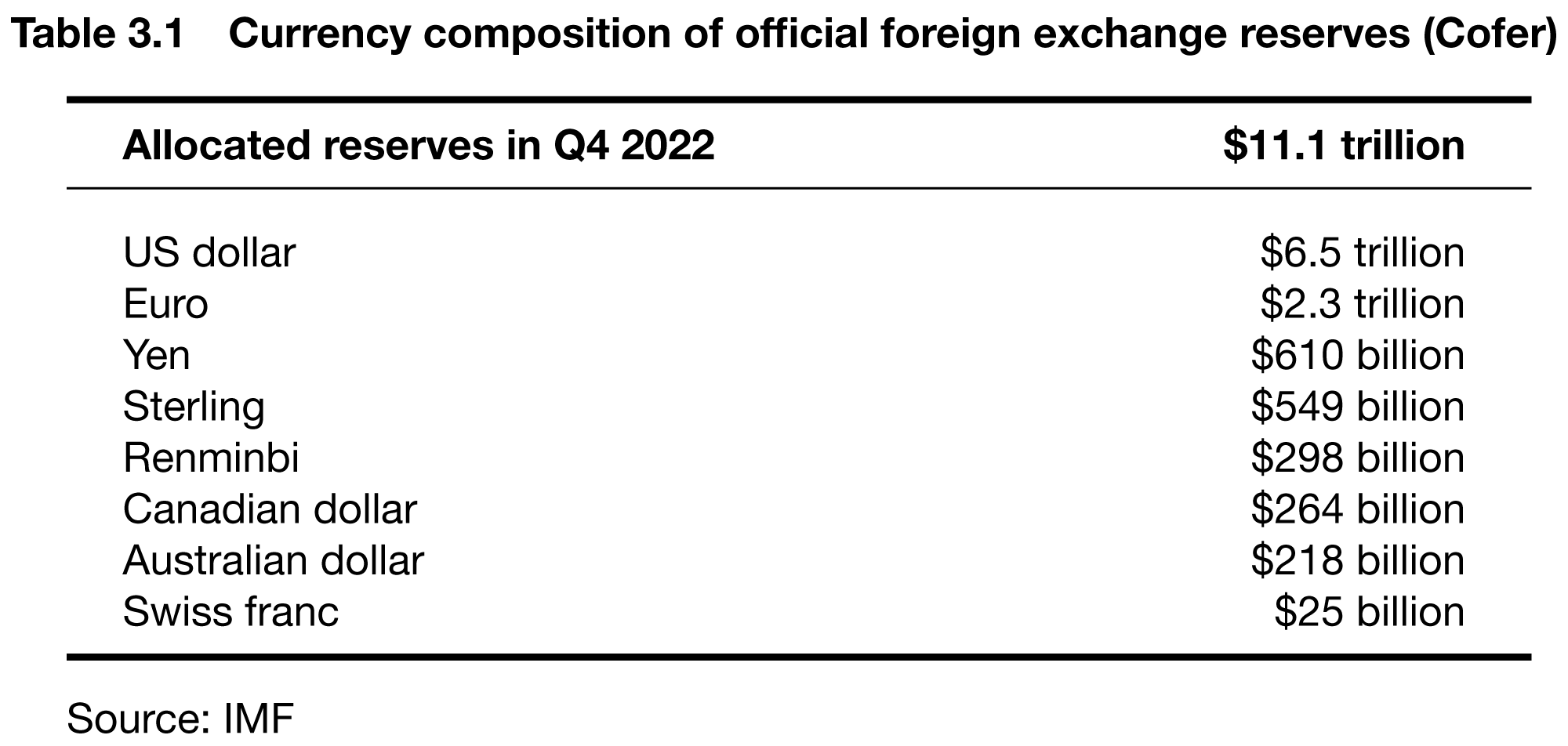

The share of global international reserves allocated to the Chinese currency was 2.7% in the fourth quarter of 2022, according to the International Monetary Fund’s Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (Cofer). Nonetheless, this is likely to rise over the coming decade. For instance, in 2022, the IMF increased the renminbi’s weight to 12.28% in the Special Drawing Rights (SDR) basket.

“In recent years, as the access to the onshore bond market became operationally easier, it was possible to develop internal capabilities to invest in sovereign Chinese assets,” says one Latin American central bank in the RMT survey.

Another reserve manager in the same region reports that it is “working on our own capabilities for investing in Chinese government bonds to expand our opportunities in this asset without having to go through an external manager”. One institution in Africa says: “Our view on China still remains the same, that it is an attractive market to invest in, and serves as a good yield diversifier to our investments.”

In this environment, the war’s ultimate risk is that it has unleashed a crisis that could end up “fragmenting the global economy into distinct economic blocs with different ideologies, political systems, technology standards, cross-border payment and trade systems, and reserve currencies”, warned Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, the IMF’s chief economist, in an article in June 2022.

Beyond geopolitics, the crisis is also exposing the increasing mismatch between the US’s financial dominance through the dollar and the decline in its relative economic size and trading relations. When the IMF was created in 1945, the US economy represented around 50% of the world’s GDP, but it now accounts for around 24%, according to fund data. And over the past four decades, China has gone from representing a negligible share of global output to reaching 17% in 2021.

From this point of view, the monetary status quo is “ultimately fragile because the US share of global output, and therefore the share of global output it can safely pledge through its official debt instruments, is bound to decline as emerging market economies rise”, Gourinchas said: “With a shrinking share of world output, the United States cannot indefinitely remain the sole supplier of safe assets to the world.”

Trade currencies

From this point of view, some observers argue China’s enormous gains since the introduction of its first market reforms in 1978 warrant a much more prominent role for the renminbi as a reserve currency.

According to World Bank data, China was the world’s leading exporting nation, with exports amounting to $2.5 trillion in 2019, up from $85 billion in 1992. US exports stood in second place at $1.6 trillion. However, this is not reflected in global reserves portfolios. According to IMF data, in the fourth quarter of 2022, allocated reserves amounted to $11.1 trillion (see table). Of these, $6.5 trillion were claims in US dollars (58.6% of total reserves), and just $298 billion in renminbi (2.7%). This means dollar holdings are more than 20 times greater than renminbi.

“I think the level of renminbi reserves as a percentage of global reserves is outdated, because pretty much for every country outside of Mexico and Canada, China is going to be the biggest trading partner,” says Jon Turek, founder and CEO of JST Advisors, a US hedge fund advisory service.

“Now, that trade will still largely be settled in dollars unless the Chinese capital accounts can be fully liberalised.”

The fact that China’s currency is non-convertible and the government tightly controls its financial markets help to explain the limited role the renminbi plays as a global reserve currency. Notwithstanding this, the Chinese government is trying to find ways to circumvent these obstacles and boost the use of its currency in international trade. For instance, in March 2018, it launched its first crude oil futures contract in Shanghai, and, in 2022, The Wall Street Journal reported Saudi Arabia was studying the possibility of accepting renminbi rather than dollars for its Chinese oil sales.

“If trade starts to be denominated in other currencies, if that is something that starts to happen on a wider scale, then it will affect reserve allocation decisions,” says the head of reserves at an emerging markets central bank. “In that case, you wouldn’t necessarily need as many dollars for you to settle trades in the future to, for instance, buy and sell commodities.”

In this context, the Russian invasion of Ukraine could have contributed to bolster efforts to use other currencies in international trade.

“I believe the sanctions have intensified ongoing conversations around invoicing international trade in different currencies,” says BlackRock’s Mateos y Lago. “Are we going to see more than 50% of global trade invoiced in another currency other than the US dollar, any time soon? Probably not. But I think there’s a tendency to dismiss changes that are happening slowly. You can’t see them from month to month, but it doesn’t mean it’s not happening.”

A liquid safe environment

Observers who tend to stress the dollar’s resilience point out that the liquidity and depth of US debt markets, combined with a solid rule-of-law system and the safe-haven status enjoyed by US Treasuries, make the greenback an unbeatable option. The US Federal Reserve has also demonstrated its commitment to ensure the liquidity in both the US dollar onshore and offshore markets and rising US interest rates make returns on dollar assets more attractive.

“The most important issue for central banks is liquidity,” says Marco Ruiz, engagement manager for the Reserve Advisory & Management Partnership, within the World Bank Treasury. As of March 2023, the level of outstanding US Treasury securities stood at $24.3 trillion – a much larger level than any other safe-haven jurisdiction. By way of comparison, the total volume of outstanding tradable German securities stands now at €1.75 trillion ($1.88 trillion).

Ruiz stresses that market size is key for any currency to acquire a global reserve status: “In fact, the size of the Chinese government debt market is large, much larger than in some developed markets.”

By the end of January 2023, the total outstanding amount of bonds under custody in China’s bond market hovered around 145 trillion yuan, almost $21 trillion, but foreign institutions held just 2.3% of it, according to the People’s Bank of China. This may be partly as a result of liquidity concerns. “Central banks must assess how easy it is to liquidate your positions in the Chinese bond market and convert these holdings into other currencies,” adds Ruiz. “Probably, this is the area where more work needs to be done to make it easier for central banks to trade in Chinese securities.”

The emerging market reserve manager says developed markets in the US, Europe, Japan, UK and Canada offer a common market with plenty of financial products to transparently invest in. “Beyond government debt, you have corporate bonds, equities, you have a whole list of assets and curves to follow,” says the official. “But when you look at China, there are a lot of reasons for concern. There is a lot of government intervention, with the real estate market being just one example.”

This reserve manager points out the difference between the relative certainty associated with owning Chinese government debt, or securities issued by state-owned enterprises, and the uncertainty and lack of transparency associated with equities, or other corporate assets. “Financial markets in China need to develop further for you to be comfortable not only owning government assets, but corporates as well, even if you’re not going to buy them,” they say.

Diversification

Despite the seemingly unbeatable traits that the dollar enjoys, its share of global reserves has progressively declined over the past 20 years. Research published in March 2022 by economists Serkan Arslanalp, Barry Eichengreen and Chima Simpson-Bell finds that the dollar’s share declined from around 71% of total central bank allocated reserves in 1999 to around 59% in 2021.

Somewhat counterintuitively, the renminbi only accounted for one-quarter of the shift away from the greenback. And the wider international adoption of the currency could be even more limited. Notably, by the end of 2021, Russia held close to one-third of its global reserves in the Chinese currency. Other traditional reserve currencies, such as the euro, the yen and sterling also made only limited ground. Instead, the recipients of most of these transfers away from the dollar were a group of developed, western-allied, mid-sized economies. These currencies included the Australian and Canadian dollars, the South Korean won, the Singapore dollar and the Swedish krona.

Arslanalp, Eichengreen and Simpson-Bell stress two factors contributing to boost currency diversification. First, in the years between the global financial crisis and the post-pandemic inflationary shock, interest rates in the US, the eurozone and Japan remained close to historic low levels. Furthermore, the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank or the Bank of Japan implemented large quantitative easing programmes, depressing returns.

In contrast to them, the group of smaller advanced economies offered relatively higher returns and low volatility. “This appeals increasingly to central bank reserve managers as foreign exchange stockpiles grow, raising the stakes for portfolio allocation,” say the authors.

Additionally, “new financial technologies – such as automatic market-making and automated liquidity management systems – make it cheaper and easier to trade the currencies of smaller economies”, say Arslanalp, Eichengreen and Simpson-Bell.

Another factor favouring diversification is the push towards active reserve management. According to the authors, among 56 emerging market central banks, 30 recorded excess reserves by the end of 2020, up from nine in 1999. This offered the option to allocating a part of these excess reserves to tranching strategies, which separate central bank reserves into liquidity and investment portfolios.

“In these countries, total reserves exceeded the IMF’s minimum adequate reserve levels by 58% on average, thereby providing a sizeable ‘investment tranche’,” says a 2022 policy briefing by State Street.

As part of this trend, last year, two central banks with large reserves communicated plans to further diversify their currency allocation. In March 2022, the Bank of Israel said it was going to adopt a broad currency benchmark of seven currencies (see Figure 3.1). This included the adoption of the renminbi (2%), the Canadian dollar (3.5%), the Australian dollar (3.5%) and the yen (5%). Their inclusion entailed reducing allocations to the US dollar from 66.5% to 61%, and the euro from 30.8% to 20%, while boosting sterling from 2.7% to 5%. This rebalancing is substantial, with the Israeli reserves portfolio standing at almost $196 billion at the end of February 2023.

The Central Bank of Brazil made public a similar move in March 2022, when it disclosed the evolution of its portfolio in 2021. That year, the US dollar declined from 86% to 80%, and the euro from 7.8% to 5%. Meanwhile the allocation to sterling rose from 2% to 3.5%, and the renminbi from 1.1% to almost 5%. Additionally, the central bank incorporated Canadian and Australian dollars within the portfolio (1% each). The central bank’s portfolio stood at $328 billion in February 2023.

Towards a new paradigm?

This gradual evolution towards a multi-currency reserves allocation has been in the making for the past two decades, and it is almost certain to continue. The question some analysts ponder, considering the unprecedented sanctions on the Bank of Russia, is whether it will accelerate or not.

“This trend is likely to be slow,” says Ruiz, who believes the domestic bond markets of mid-sized economies are not large enough to absorb the capital inflows they would experience if most central banks decided to allocate 5% of their reserves in Swedish krona or Korean won.

Nonetheless, although liquidity is of great importance, it is not the only goal reserve managers follow. Their portfolios are also used for monetary policy purposes, exchange rate management and to adequately cover the economy trade links.

“The question of alternative reserve currencies cannot be looked at independently of what reserves are used for,” stresses Mateos y Lago. “There is no other currency that enjoys the liquidity and safety of the US dollar. That’s true. But what if a significant chunk of your reserves can be invested in such a way that safety and liquidity are a secondary consideration? Then there are more alternatives.”

Others point out the financialisation of the world economy has reached a dead end. In their view, there is simply too much capital looking for returns. State Street highlights global debt reached $300 trillion in 2021, most of it denominated in US dollars. A way forward might not be changing some financial assets for others, but to reduce reserve levels to invest in real economic capacity. “If you are a major oil exporter like Saudi Arabia looking to reduce your dollar exposures, ‘what do you turn that into?’,” says Turek. “‘Could it be invested domestically?’ I think a lot of it will be. That’s probably part of what the Saudi Vision 2030 is all about, and a similar dynamic is taking place in China.”

In Turek’s view, this new trend will mark this decade. The previous framework sought a current account surplus, fiscal surplus and a big percentage of FX reserves relative to imports. The aim was to have the best external balance to create a financial fortress, like Russia tried to do. “This probably made a lot of sense,” he says. “Saudi Arabia gets $100 billion extra money effectively from oil sales. It can instantaneously turn that into a new asset. You can’t do that with the real economy.”

In Turek’s view, the new equilibrium will not revolve around the idea that sanctions on Russia ended up not affecting the international monetary system.

“To a large degree, the system will continue seeing huge amounts of international capital [being] recycled into US assets,” he adds. “But I do think this crisis will also unleash a big change on how reserve managers think about allocating their resources going forward.”

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: subscriptions.centralbanking.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com test test test

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com test test test