The role of gold in central bank reserves

James Steel

Executive summary

Trends in reserve management: 2023 survey results

The role of gold in central bank reserves

Will the dollar remain the world’s reserve currency?

Interview: Golan Benita

Reserve management at the BCB

NDF interventions in Latin America

Appendix 1: Survey questionnaire

Appendix 2: Survey responses and comments

Appendix 3: Reserve statistics

A long history

Gold is enjoying something of a renaissance among central banks. Central banks are accumulating gold at a pace not seen since the last years of the Bretton Woods system in the late 1960s. We take a look at the drivers of this surge in demand, and whether it could continue.

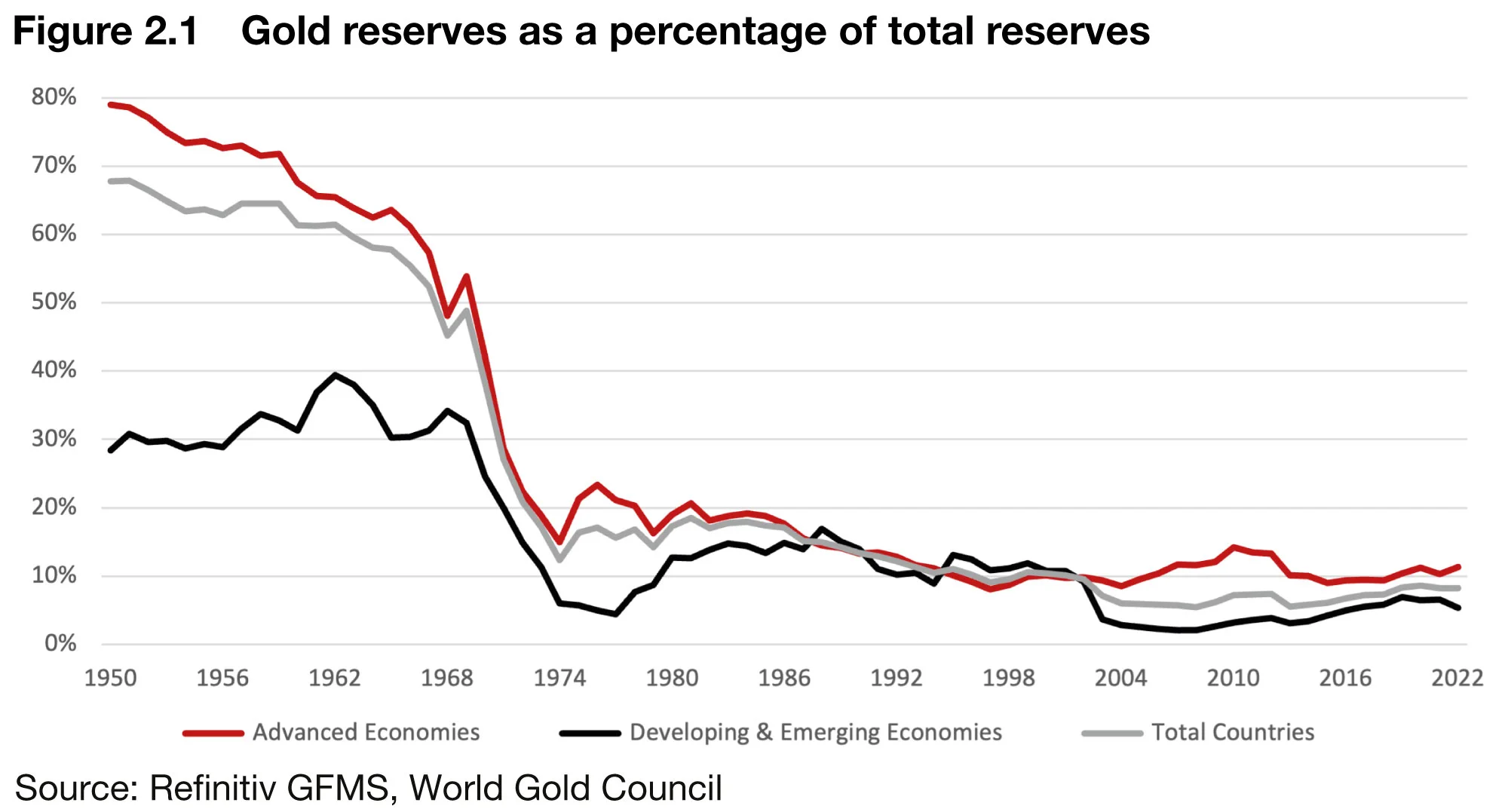

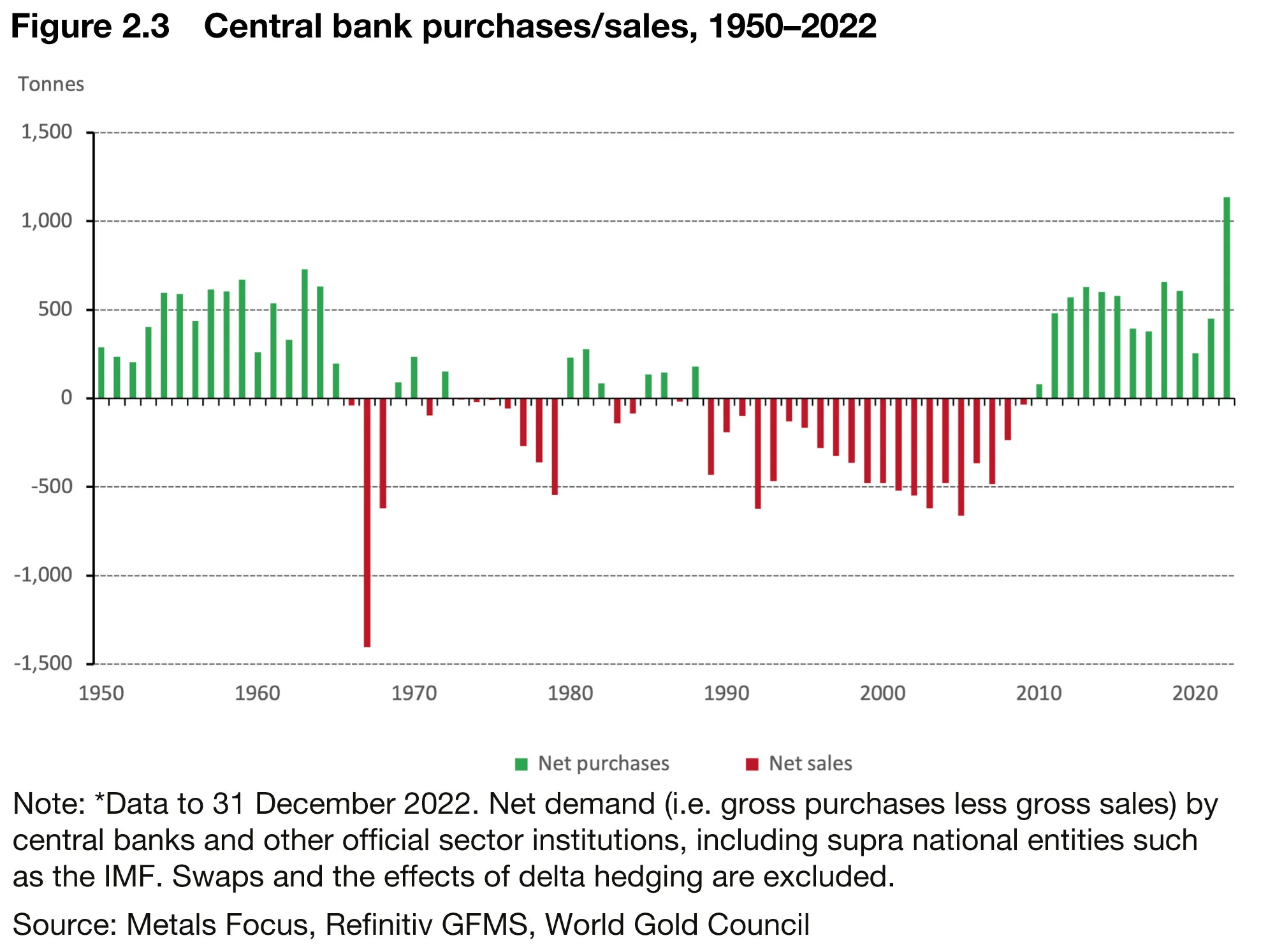

Bretton Woods was an international agreement designed to keep the US dollar pegged to gold, and other currencies pegged to the US dollar. The system worked until there was a run on US gold reserves in the late 1960s, with massive amounts of gold moving from the US to European central banks as the US ran up persistent current account deficits. This effectively ended the system by 1971. More than five decades after the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, gold continues to play a useful role in the international financial system and forms a notable share of global foreign exchange reserves. Purchases of gold by the official sector are an important (if sometimes little-discussed) component of gold demand. Collectively, central banks are the world’s largest holders of bullion, and their sales and purchasing decisions can have a significant impact on prices. Every independent central bank in the world holds at least some amount of bullion (see chart and table below).

One measure of central bank influence on gold is to make rough comparisons with other components of gold demand. Central bank purchases often outpace exchange-traded fund, coin, technological and, occasionally, bar demand. This makes official sector demand an important driver of bullion prices. Despite this material role in price determination, other components of gold demand are more commonly and openly discussed and analysed by the financial media than official sector demand. One reason for this is the often opaque nature of central bank purchases as they are often not reported on a timely and consistent basis.

Indeed, central bank purchases played a pivotal role in supporting gold in 2022, notably in the second half of the year. According to the World Gold Council (WGC) and based partly on International Financial Statistics (IFS) data, total official sector purchases hit nearly 1,136t in 2022, more than doubling the 450t of central bank demand registered in 2021. A large chunk of this estimated demand is as of yet unreported officially but which the WGC has estimated based on market activity and other indicators. This is not unusual, as not all official sector buyers publicly report their gold holdings or may do so only with a considerable lag.

Based on current estimates, 2022 purchases likely surpassed all annual totals since at least the 1960s, when the global financial system still operated under Bretton Woods. Although gold prices have moderated since hitting year-to-date highs of USD1,959/oz on February 2, 2023, we believe ongoing official sector demand has helped sustain prices this year.

Will the trend continue? We think so, as it started even before last year. Pre-COVID-19 purchases by central banks were not only high, but diverse. In 2018 and 2019, the number of central banks purchasing gold was 24, double the number in 2017, with many of them entering the market for the first time in decades. Global central bank gold reserves reached 35,425t as of December 2022, according to the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) IFS – the equivalent of nearly 10 years of mine output at current production levels. This constitutes around one-sixth of all the gold ever mined and is the largest level of official holdings since the early 1990s, increasing 12%, or around 3,700t (the equivalent to just over one year of mine production), in the last decade. Unlike previous periods of heavy accumulation, which were conducted by European central banks, this time official sector purchases are coming mostly from emerging market (EM) monetary authorities. According to data from the IMF, bullion now accounts for about 14% of total world FX reserves in 2022, up from 13% the year before.

Anatomy of holdings

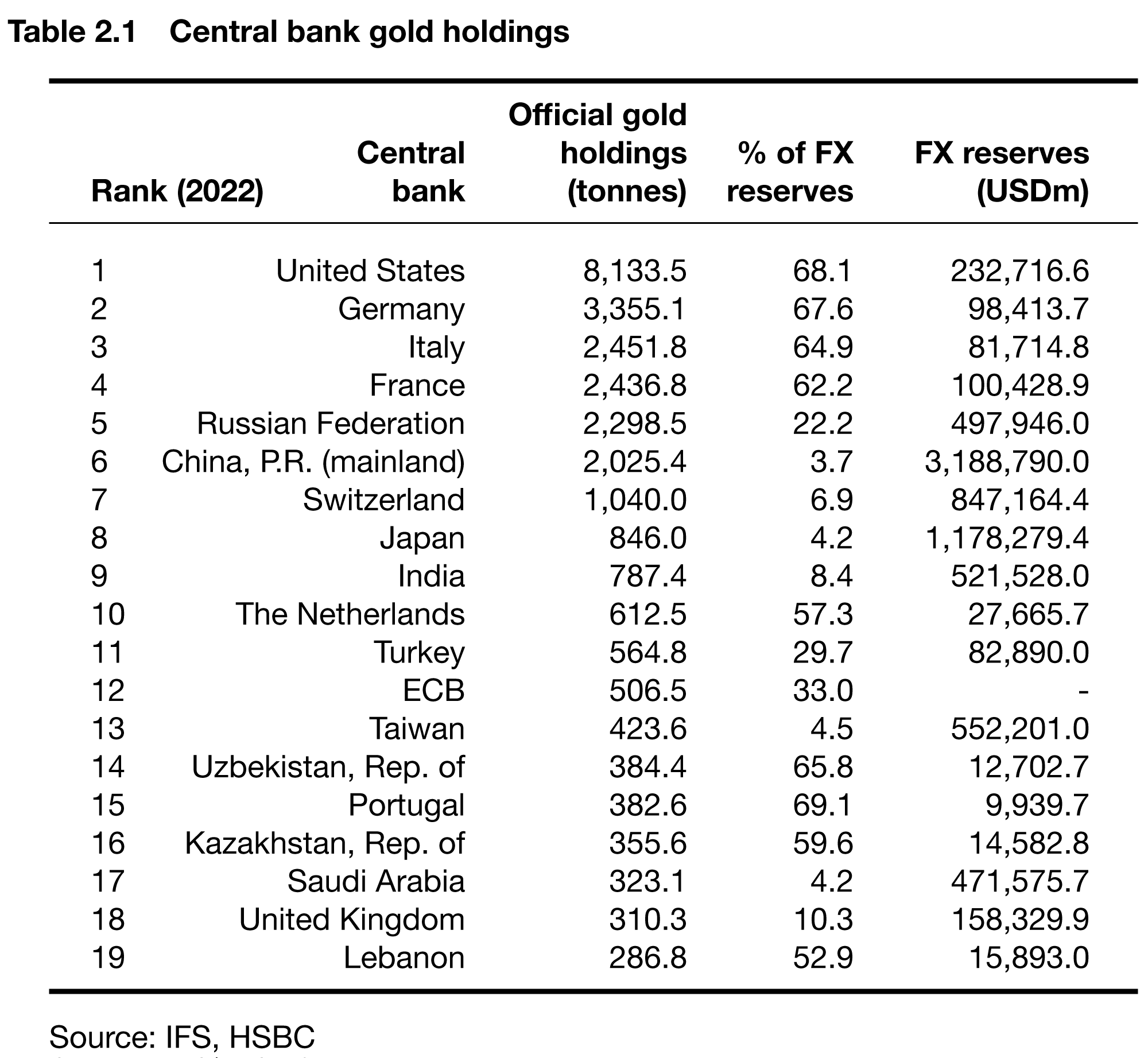

One of the most interesting features of central bank gold reserves is the broad, varied and unequal distribution of holdings. On average, governments hold around 10% of their official reserves as gold, but this varies widely, and holdings among the world’s central banks are highly skewed (see table below). Those in the euro area, including the European Central Bank (ECB), own considerable amounts of gold. The US and Japan are significant holders also, with the US the world’s largest official sector holder of bullion, accounting for a little under one-quarter of all central bank gold. The Central Bank Gold Agreement (CBGA) signatories, which are a subset of the euro area, hold about 30% of all central bank gold. Members of this group were significant sellers in the 1990s and the first decade of this century, and their sales patterns played a role in the bear market for much of that period. The CBGA, which regulated sales from signatories beginning in 1999 and was extended every five years for 20 years, officially ended in September 2019.

After decades of sales, central banks turned buyers towards end-2009, according to data from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). We believe this was prompted by a reassessment of gold’s role and utility in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis in 2008–09. This reaffirmed and enhanced gold’s value in central banks’ foreign exchange reserves. Despite robust purchases in recent years by EM central banks, holdings continue to be overweighed to OECD banks.

Although some smaller EM central banks may hold relatively low amounts of physical gold, this may still translate into a large percentage of their total reserves, given correspondingly low currency reserves.

Gold functions

What is the rationale behind a central bank maintaining existing holdings or increasing gold reserves? While gold no longer plays a pivotal role in international finance, it is still regarded as a valuable component of a nation’s foreign exchange reserves. Some of the reasons that reserve managers choose to hold gold include:

-

Portfolio diversification. Gold can serve as a portfolio diversifier and reduce the risk of holding currencies and debt instruments of other nations. Gold purchases can be a way of reducing heavy USD holdings.

-

Risk reduction. Lack of credit risk as gold does not have counterparty risk.

-

International payments. Gold can be utilised in a balance of payments crisis such as occurred in the 1997–98 Asian crisis and can be utilised to cover essential imports or shore up a domestic currency. It can also serve as collateral for loans.

-

Emergency funding. Reliable in emergencies. In times of national emergency or conflict when national currencies may not be redeemable, gold can be mobilised.

-

Legacy. Many developed market central banks hold substantial amounts of gold by way of legacy, dating from decades ago.

-

Prestige. In the case of some EM central banks there may be a tendency to emulate OECD gold holdings.

Academic studies show gold purchases can enhance a central bank’s creditworthiness

Despite its antiquity, gold is still a useful and robust component of a central bank’s portfolio, and holdings in many central banks are far from static. Reserve managers’ allocation decisions regarding gold depend on a myriad of factors including policy objectives, risk tolerance, costs, and the like. A BIS Working Paper, What share for gold? On the interaction of gold and foreign exchange reserve returns, by Omar Zulaica (November 2020), examines the issue. The paper found that some level of gold in a central bank portfolio is required, but in many cases and under most scenarios, only modest amounts of gold may be necessary in a central bank portfolio due to gold’s volatility.

There is a risk in owning gold, given market fluctuations. The paper finds that although the market risk associated with gold is substantial, it may not be apparent in the reserve portfolio’s performance if accounted for at historical cost on the balance sheet, which is the case with some central banks. That said, the paper also finds that for central banks with higher exposure to interest rate risk, and also for those managers who measure returns in a non-reserve currency, gold appears a relatively less risky addition to a portfolio. Based on this, there is strong evidence that gold may function as a hedge, making it easier to justify large gold holdings. In some cases, as the interest rate sensitivity of a bank’s fixed income portfolio increases, adding gold can lower the volatility of the portfolio. Evidence of the potential insurance value of gold in adverse economic conditions. Thus, an argument can be made for substantially greater allocations of gold in cases where protection against tail risks is a driving concern for a central bank. Given the current high levels of economic and geopolitical uncertainty, there could be increased appetite to mitigate tail risks. Increasing gold reserves may therefore be attractive, especially for those with low overall reserves. This paints an especially good reason for smaller EM central banks to be favourably disposed to gold.

Gold has traditionally offered reserve managers a range of other benefits, such as the absence of default risk, and in highly adverse scenarios, a country’s stock of bullion could be one of the last guarantors to ensure confidence and financial stability. This was the case when the central bank of South Korea mobilised its gold reserves during the 1997–98 Asian crisis.

A more recent paper, Central bank gold reserves and sovereign credit risk (March 2021), by Sawan Rathi, Sanket Mohapatra and Arvind Sahay, of the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad, shows that gold reserves with central banks can be beneficial for a country’s sovereign creditworthiness. In a post-Global Financial Crisis world, this can be an especially compelling argument for a central bank to accumulate gold. Using data from 48 emerging market and developed countries, the paper shows that when central bank reserves rise, sovereign credit default swap spreads for a country tend to decrease. This indicates reduced country risk. The paper also shows that during global crises, increased financial market volatility and domestic crises, the role of central bank gold can become even more important. The findings highlight the importance of gold in central bank reserves and indicate a positive role for gold in mitigating a nation’s vulnerabilities in the international arena in an uncertain global economic environment.

These academic works show how gold provides key value as a risk diversifier, as well as acts as potential insurance and affords protection in adverse scenarios. Both papers generally support reasons for greater official sector gold accumulation. These papers find that central bank holdings are considered to play a stabilising role, especially in times of crisis. In the case of emerging market central banks, gold holdings contribute to sovereign creditworthiness.

Portfolio diversification

Portfolio diversification at central banks may also favour buying gold. Many central banks are USD-laden, and, while the USD is likely to remain the world’s principal reserve currency for the foreseeable future, some central banks may wish to modestly reduce the level of USD holdings. In a multipolar world, many countries may wish to reduce their dependency on one currency. While gold can provide diversification, a sizeable amount of USDs is still needed by central banks to pay for imports and finance external debts. But these reserves are mostly made up of US Treasuries, not hard currency. As the Federal Reserve has raised interest rates, buoying yields, the value of government paper has fallen. Historically, at times of rising yields, there has been greater buying of gold. In addition, many central banks are limited in what assets they can hold, and may be reluctant to commit to other currencies. Therefore, they may find gold an attractive alternative. Gold can also be used to make payments for imports instead of USDs. Also, unlike currencies and debt – which are claims on foreign governments or institutions – gold can be kept domestically and is also durable and largely imperishable and has no counterparty risk, which only adds to its status of being free of default risk.

Geopolitics front and centre

Although it is hard to quantify, holding gold may afford EM central banks increased independence from the major central banks. Some EM central banks, as a reflection of growing economic and geopolitical clout, may decide to increase gold reserves.

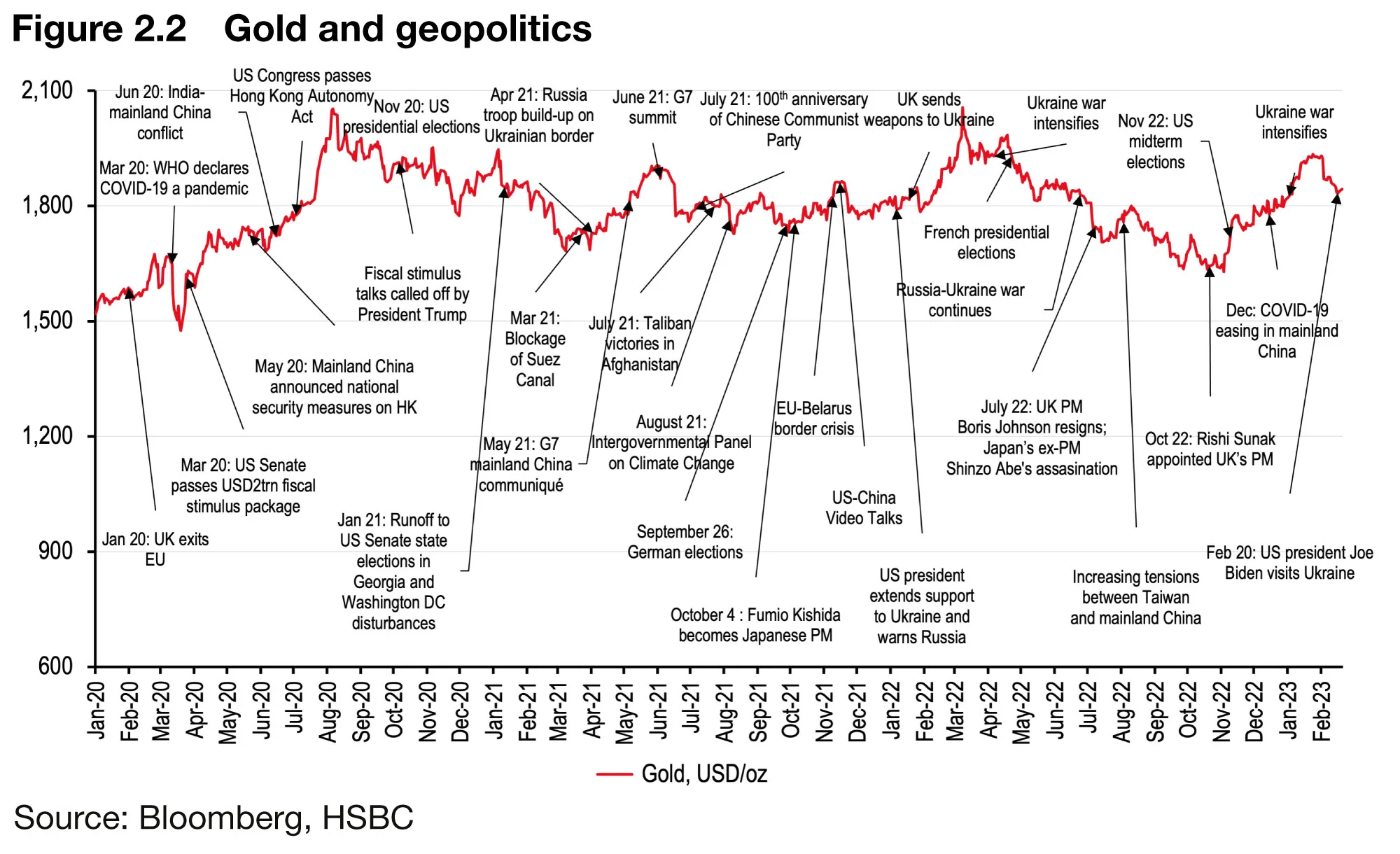

That said, gold is sensitive to geopolitical risks, especially in cases of outright military conflict. Increased risk-off investor sentiment can also have pronounced negative impact on equities. This serves to increase the safe-haven demand for gold, which has a reputation as a tried-and-trusted asset for all the reasons described above. The positive association between gold prices and increased geopolitical risk is supported by empirical studies, which show that gold exhibits positive behaviour among commodities – and also outperforms other precious metals – to such risks. Gold has a history of rallying independently of other commodities during periods of risk aversion. This supports gold’s status as a global safe-haven asset. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 sharply stimulated the safe-haven demand for gold in the early days of the war. Historically, once geopolitical risks recede, gold often retraces, giving up most, if not all, of its safe-haven-inspired gains. There are other examples of geopolitics impacting gold than the current Ukraine crisis: these include February 2014, when Crimea was invaded, September 11, 2001, with the destruction of the Twin Towers, and even the Brexit vote and flare-ups in East Asia. In every case, gold rallied notably on a percentage basis, but gave up the bulk of gains in the following days. This might on the surface argue against gold’s utility in this regard.

A casual look at any particular geopolitical event may be misleading as gains may appear modest. One of the findings in Gold and geopolitical risk (Dirk Baur and Lee Smales, University of Western Australia, February 2018) is that the frequency of what is termed a geopolitical event is increasingly lending support to gold, but that after any particular event, gold tends to relax. Any reversal of globalisation and an end of the ‘peace dividend’ could be supportive for gold. The impact of Ukraine may be longer-lasting than most recent geopolitical events. And this has ramifications for gold.

In his March 2022 essay Is the peace dividend over?, Kenneth Rogoff, Professor of Economics and Public Policy at Harvard University, states that for many decades, Western living standards have been boosted by a massive “peace dividend” due to the end of the Cold War. This same dividend helped lower inflation, boost equities, and generally contributed to political and economic stability globally, all of which reduced uncertainty. The strongest period of globalisation, the 1990s and early 2000s, saw a reduction in the need to own safe havens and contributed to persistently weak gold prices.

Ian Bremmer, president of the political risk consulting firm Eurasia Group, has said the war in Ukraine has abruptly ended the “peace dividend”. This ramp-up of national security within Europe will be permanent, Mr Bremmer said, along with deployments of military forces in the Baltic states. As the “peace dividend” created an environment less supportive of gold by reducing uncertainty, a shift could be a supportive development for gold. Already the swings in commodity prices and financial markets have been dramatic, and volatility looks set to be a feature of the outlook for the foreseeable future, much of it as a consequence of geopolitics. Charged with safeguarding a nation’s economic wellbeing, it is not surprising that the current global conditions have elicited greater central bank gold purchases.

Gold comes back

Where can we trace the comeback of gold as regards central bank utility and interest? A long series of central bank gold sales, beginning in 1991, began to peter out in the early part of this century. The end of the Cold War, reduced geopolitical risks, and era of increased global trade and prosperity, seemed to consign gold to the back burner. The Global Financial Crisis in 2008 seems to have brought gold back to investors’ attention, including central banks. The buying continues. In an IMF Working Paper, Gold as international reserves: a barbarous relic no more? (January 2023), Serkan Arslanalp, Barry Eichengreen and Chima Simpson-Bell point out that in addition to many of the points already covered as to why reserve managers would wish to accumulate gold – safe haven, portfolio diversification, etc – there is an additional reason that has only presented itself comparatively recently.

Mr Eichengreen and the other authors observe that gold holdings may have a particular appeal for countries as a way to mitigate the impact or risk of sanctions. Sanctions may limit or cut off access to US dollars. This can lead to the utilisation of gold in its place. One example cited in the paper is the so-called ‘oil for gold’ mechanisms which were initiated with other countries, starting from 2012. Since 2000, a number of central banks in large emerging economies have significantly increased their gold holdings, including: mainland China, Russia, India and Turkey.

Another, less well-known, reason for the increase in central bank reserves is that in certain gold-producing countries, the central bank is committed to buying a set proportion of domestic output. This may mean that countries with domestic gold production have even higher gold reserves, unless domestic purchases are immediately disclosed.

Despite new central bank entrants and increased purchases, Mr Eichengreen makes the point that, with the exception of several discrete step adjustments, central banks maintain passive gold stocks independently of the market price of gold. There is also some synchronicity to central bank purchases (as there was with sales decades ago), although there is no clear reason for this.

This change of trend in central bank net purchases is well illustrated by the chart below.

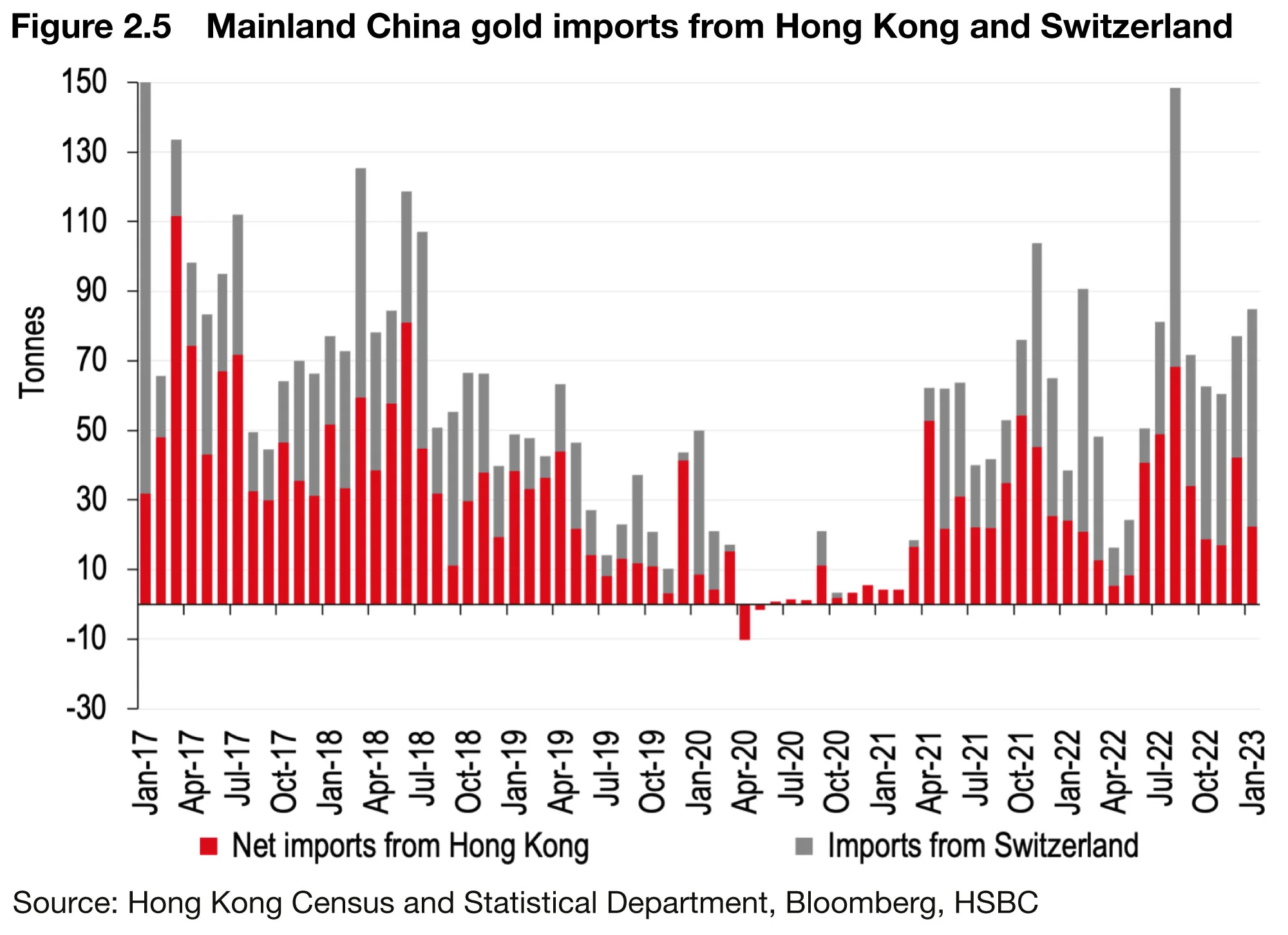

A word on the physical market

Central banks compete with other purchasers and consumers for gold. Understanding their motives may help reserve managers make purchasing and sales decisions and assess market prices. Mainland China and India together regularly account for about 50% of all the gold jewellery purchased globally. In 2021, this climbed to 60% with the combined demand from both nations. The portion of jewellery in underlying physical demand doubtless remained high in 2022. Import data so far for 2023 are mixed, with India down compared with the previous year, but mainland China up. Mainland China is the world’s largest gold consumer, and can attract the equivalent of as much as 40% of global mine production as imports in normal years. The latest official customs data show mainland China imported 48.4t from Hong Kong and Switzerland in January 2023, down 49% year on year from 94.7t in January 2022. Imports in 2022 were quite strong totalling 818.3t up 34% from 2021 imports of 608.8t, as demand recovered from a dip earlier in the year in response to surging prices in the wake of the invasion of Ukraine.

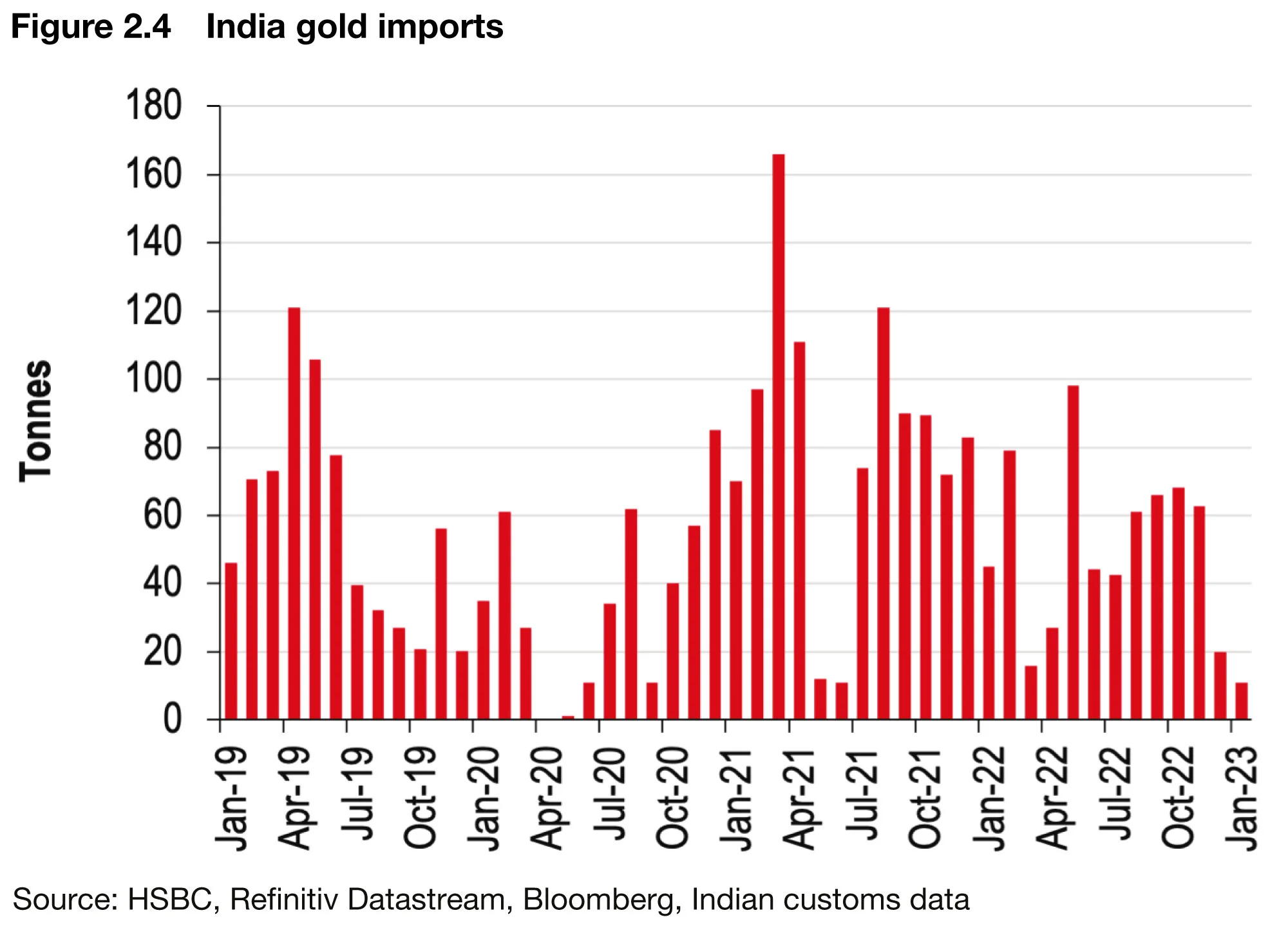

India’s imports are a little less impressive. India’s imports in January 2023 hit just 11t, down 76% year on year from 45t in January 2022. Total 2022 imports came in at 629.5t, down 37% from 2021 imports of 996.5t. The decline is due in part to Indian government import tax increases, which helped curb imports. For these two giants, this implies jewellery demand in India may begin to slow while looking firmer in mainland China, unless January’s weaker imports carry over into 2023.

HSBC economics points to two important factors supporting mainland China’s economy and, hence, jewellery demand. Policymakers recently announced a relaxing of COVID-19 controls, as well as a slew of policy measures to help stabilise the housing market. Also, monetary policy remains accommodative. For 2023, HSBC expects growth to accelerate to 5.6%, from 3% the year before, with momentum carrying into 2024, when growth may reach 5.5%.

As with mainland China, Indian demand faces some economic risks. The economics team caution slowing 2H demand, which may spill over into 2023. The Indian government introduced a higher import duty on gold imports earlier in 2022, which has notably impacted bullion imports. India is usually the first- or second-largest importer of gold bullion in the world and the second-largest consumer after mainland China. India’s growth should be strong enough to support a minimum of demand although HSBC’s economics team points out that some key drivers of growth are now softening. Inflation has peaked and should moderate meaningfully in 2023 in the team’s view, from 6.6% in 2023 to 5.2% in 2024. This may moderate gold demand. The two charts below show mainland China and India imports.

The outlook for jewellery demand in the rest of the world is more mixed. Unemployment should stay low enough to support demand in the OECD, but this will be offset by slower growth. Higher oil may support demand in oil-exporting countries. The ongoing Ukraine conflict is a drag on demand in Eastern Europe. A further weakening in the USD could generally offer support for gold jewellery outside the USD bloc. The key factor going forward may be higher prices, which inhibit price-sensitive demand. A precipitous fall in prices to, say, below USD1,700/oz, would support jewellery appetite. High inflation, although stimulating appetite for gold, may also help to restrict investors’ ability to purchase bullion (via lower real incomes), but CPI indices may be easing in any respect. A price climb above USD1,900/oz and especially above USD2,000/oz would likely further contain jewellery demand.

Coins & bars

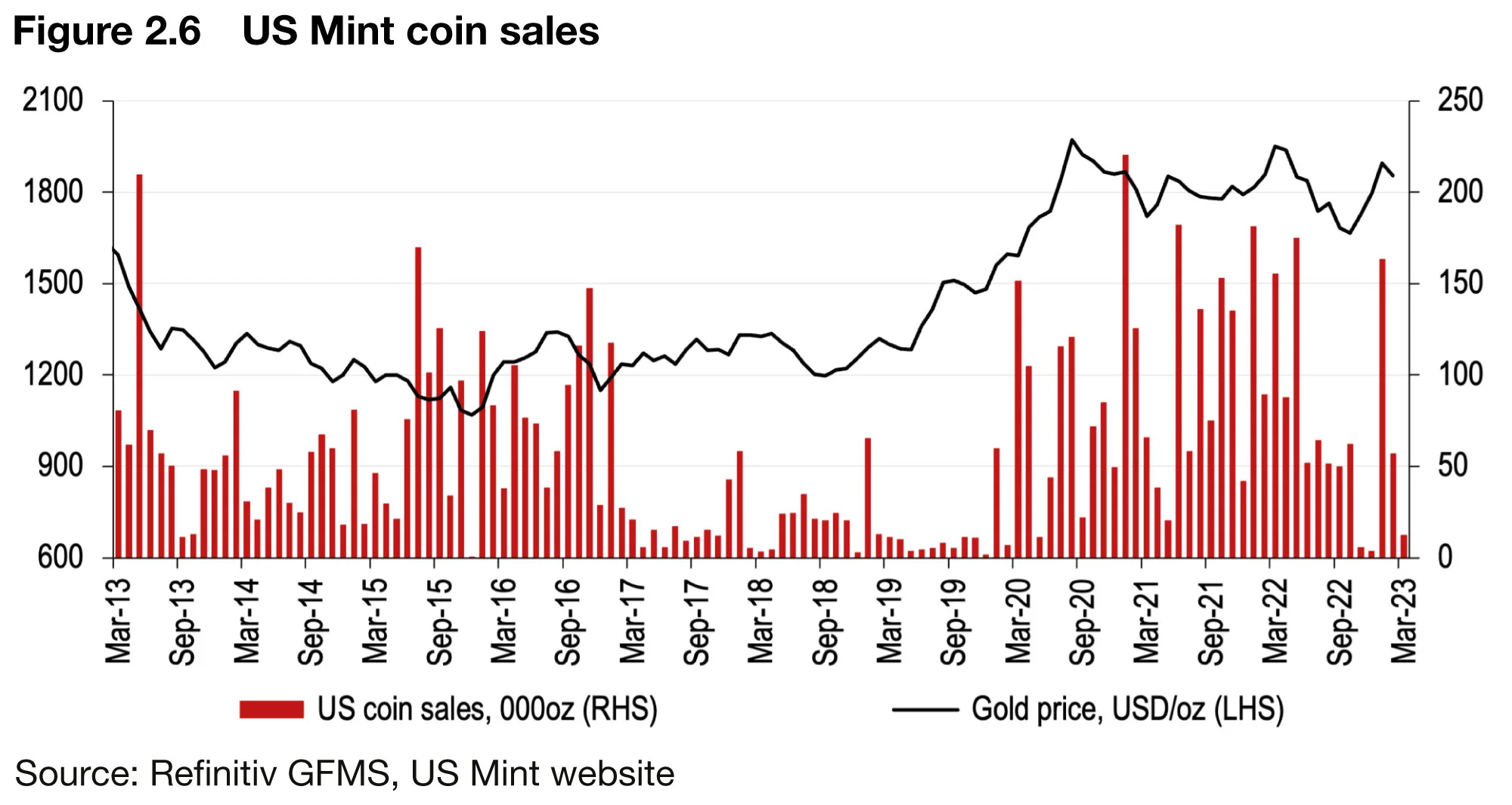

Gold bar & coin purchases, while traditionally a smaller contributor to demand than jewellery, are still an important component of overall demand. This segment also provides a good window into retail sentiment. Combined bar & coin demand jumped 32% to 1,179t in 2021, from 896t in 2000. Demand, however, was heavily skewed toward bars. Global bar & coin demand in 2022 improved on the already healthy 2021 total, gaining 2% to 1,217t.

Coin data are more readily available than bars. The US Mint is the largest producer of gold coins in the world and is usually a good barometer for global demand. Using the latest data for the year to date (January–March 2023), the US Mint sold 233,000oz of gold coins, compared with 426,500oz for the same time last year. A decline in recent months may not represent a real drop in demand, but possible near-term supply chain constraints, as the premium on secondhand coins is still high, and blanks, from which coins are struck, are in short supply. Based on robust coin demand for 2022, as well as high inflation, geopolitical risks, and economic uncertainties, coin & bar demand may remain historically strong in 2023 but could dim from 2022 levels. There is often a contrast between OECD and EM markets with regard to bar & coin demand. OECD markets are often more motivated by inflation concerns, while EM purchases are often strongly linked to jewellery demand. The high premiums charged for coins are moderating demand, and may be a sign of some retail market retreat, but we still expect demand to be high this year and support prices.

We look for ongoing high levels of gold purchases by the official sector to continue

There are currently good arguments for central banks to continue to accumulate gold although high prices may deter near-term purchases. In summary:

-

Geopolitical risks have escalated, impacting virtually every economy. Increased gold reserves may offer some buffer to uncertainty.

-

Near term, central banks of the nations most affected by the Ukraine crisis do not appear to have significantly liquidated holdings, and we believe the proximity of the conflict may encourage some in Europe to buy.

-

Higher oil prices could encourage demand from petro economies.

-

Gold in FX reserves can act as a stabilising force, especially for smaller central banks.

-

Renewed concerns over government debt levels as interest rates rise, may trigger appetite for gold as a portfolio diversifier.

-

A potentially weaker USD is an additional inducement to buy gold.

-

While the USD remains the dominant reserve currency, any undermining of its status, for whatever reason, is likely to result in increased central bank gold holdings.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: subscriptions.centralbanking.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com test test test

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com test test test