How can reserve managers escape low yields – and stay true to their mandate?

Mario Torriani

Executive summary

Trends in reserve management: 2022 survey results

Interview: Gerardo García

Central bank digital currencies: 10 questions

Rethinking equity investing at the National Bank of Austria post-2020

How can reserve managers escape low yields – and stay true to their mandate?

Reserve managers weigh the risks amid the Ukraine crisis

Appendix 1: Survey questionnaire

Appendix 2: Survey responses and comments

Appendix 3: Reserve statistics

In recent years there has been growing interest among reserve managers in increasing the expected returns on their portfolios. The rapid accumulation of reserves, especially in emerging market countries, has led to a greater range of assets under management and heightened the need to generate results. This dynamic has been set against a backdrop of accommodative policies at central banks which has brought nominal interest rates down close to zero or even into negative territory rates in some countries. This has added yet more incentive to search for alternatives that may increase expected returns.

However, the search for higher yields implicitly means a search for higher risks. Therefore, when searching for higher yields, reserve managers have to be very cautious about which risks are worth taking and which are not, since decisions on a central bank’s portfolio of reserves can affect the risk profile of that country’s balance sheet.

Traditionally, risk is defined in financial terms as the volatility of expected returns on a portfolio of financial assets, while diversification, through low or negatively correlated assets, focuses exclusively on improving the risk/ return ratio of the portfolio. Nevertheless, central banks are often exposed to challenges that go far beyond their portfolio of financial assets. Whether they are conducting foreign exchange policy, supporting monetary policy or acting as a lender of last resort to safeguard financial stability, they typically have to deal with contingent liabilities that may draw down reserve assets in much greater quantities and at a much faster rate than expected. Indeed, changes in the reserve portfolio caused by the performance of these functions may have more impact on the volatility of the portfolio than changes due to the market value of the financial assets in the portfolio.11 See, for example, D. Gray and S. Malone, Macrofinancial Risk Analysis (Chichester: John Wiley, 2008), for a contingent claims framework explaining the risk transmissions among the different sectors (corporate, banking, households and public sector); or Eduardo Levy Yeyati and Federico Sturzenegger, “A Balance-sheet Approach to Fiscal Sustainability,” Business School Working Papers, Universidad Torcuato Di Tella (2007) for a balance-sheet approach of the public sector.

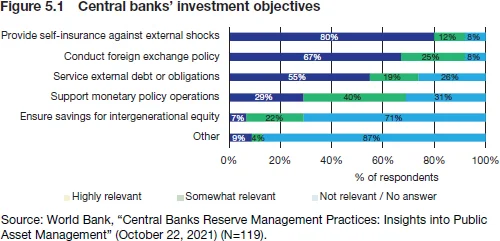

Why do central banks have reserves? While there are various objectives for holding reserves, and these objectives undoubtedly shape crucial decisions for reserve management and asset allocation, for most central banks the self-insurance against external shocks remains the primary objective for holding reserves, as a recent survey attests (see Figure 5.1).22 See World Bank, “Central Banks Reserve Management Practices: Insights into Public Asset Management,” (October 22, 2021), p.13.

Indeed, the rapid accumulation of enormous reserves has been a phenomenon that most countries have adopted with a view to preventing exposure to volatility of capital flows or mitigating their impact. Emerging market countries, which are in the predevelopment phase, are the most exposed to borrowing against their post-development income. They typically run current account deficits (borrowing from abroad and in foreign currency) to increase their current consumption, pledging future income to finance these deficits. The counterpart to these deficits is a reliance on capital inflows, which can suddenly stop. When a sudden stop occurs, the immediate implication of such a restriction is a sharp rise in the marginal value of an extra unit of foreign exchange reserves.33 See, for example, R. Caballero and S. Panageas, “Contingent Reserves Management: An Applied Framework,” MIT Department of Economics Working Paper, 04–32 (2004).

Yet, while the correlations between different investment strategies for reserves and the most common external shocks for a country will yield valuable insights for a central bank, these changes in the marginal value of an extra unit of reserves can be overlooked in the traditional process of asset allocation of reserves, if this process is confined to merely optimising the financial assets in the portfolio.

Investment strategies that can help hedge a country’s exposure to external shocks – ie, they increase the market value of the reserves portfolio at a time when those reserves are most needed – can contribute to enhancing the risk management of that country’s balance sheet. As a result, such strategies have a valuable payout over those that do not. It follows, therefore, that when searching for higher yields, reserve managers should pay attention to those strategies that can adequately compensate for taking on such additional risks – or at least they should avoid adopting strategies that could be add to the main risks and vulnerabilities of that country. Indeed, if one takes a step back: as the professed motivation for accumulating these reserves is to self-ensure against external shocks, is it not strange that such shocks are absent from the decision-making process around what to do with the reserves? There is a fiduciary element to this as the reserves are not costless: there are both real and opportunity costs of funding. But more broadly, does credibility not require a central bank to take shocks into consideration, if that is why it says it has the reserves?

But such a non-contingent approach can work against the central bank’s interests in another way. While it is true central banks normally invest “through-the-cycle”, trying to choose an appropriate strategic asset allocation consistent with their main long-term objectives, they are also highly averse to reputational risks when managing reserves. So if there are “safe-haven” assets that usually perform very well during episodes of financial turmoil (ie, when reserves are most needed), the volatility of such assets (eg, long-term US Treasuries) in “normal times” could be too high for those central banks with non-contingent strategies who prefer not to have negative returns (at any point) over the short term.

The reflation scenario and the recent shift observed in the US yield curve due to a less accommodative monetary policy expected from the Federal Reserve is an example of how negative changes in the market value of the reserve portfolio can compromise reserve managers with non-contingent strategies during short-term periods, pushing them to further shorten the duration of their reserves portfolio to avoid the risk of running into the red on the quarterly report. However, it is in these scenarios of global expansion that reserves are least needed and, as a result, the marginal utility of an extra unit of reserves is less important. Ultimately, the challenge for a central bank is how to manage market expectations and reputational risks through a stronger communication policy, or at least through the implementation of market risk limits.44 See, for example, P. Orazi, M. Torriani and M. Vicens, “Strategic Asset Allocation of a Reserves Portfolio: Hedging Against Shocks,” Working Paper No. 88, Central Bank of Argentina (July 2020), for a hedging implementation framework with market risk limits. Underperformance of the reserve portfolio when there is a positive shock to the country is likely to be much less of a concern than underperforming when reserves are most needed.

Broadly speaking the question for a reserve manager is should the “hedge” or “yield” prevail? Here there is trade-off in terms of efficiency. An allocation that will be optimal for hedging purposes will be sub-optimal from a long-only portfolio perspective, and vice versa. The higher the allocation in long-term bonds, for example, the better the hedge provided, as such assets will typically perform well when the reserve are needed. However, these assets will also have a higher return-at-risk and therefore lead to greater volatility in the portfolio. Reserve managers therefore have a choice to make when it comes to optimising their portfolios. With non-contingent strategies, they are implicitly making the decision not to hedge against external shocks.

This chapter will show how the three traditional sources used to increase expected returns – a longer duration, a higher credit and/or currency risk exposure – can impact the risk management of a typical emerging market country exposed to external shocks. The first section examines the impact of duration decisions, the second assesses the impact of credit risk decisions, and the third section examines the impact of currency risk decisions. The chapter ends with some thoughts on the opportunities offered by the breakdown of covered interest rate parity and offers some concluding remarks.

Duration risk can help central banks to mitigate external shocks

Safety and liquidity have been the two core principles guiding the investment of reserves. As a result, most reserve portfolios are concentrated in high-grade fixed income instruments with low sensitivity to changes in interest rates, where the duration of reserve portfolios is on average largely stable at one to two years.55 See Nick Carver and Robert Pringle (eds), HSBC Reserve Management Trends 2021 (London: Central Banking Publications, 2021), p. 19. Although some central banks have split their reserves into a “liquidity” and an “investment” tranche as a helpful mechanism to lengthen the portfolio’s investment horizon, the investment tranche has also been reported with a median duration of only 22 months (see Table 5.1).66 See World Bank (2021), p. 22.

| Liquidity tranche | Investment portfolio tranche | Total portfolio | Total (untranched) | |

| Min | 1.0 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Max | 60.0 | 120.0 | 48.0 | 72.0 |

| Median | 6.0 | 22.0 | 14.0 | 20.0 |

| Average | 8.4 | 25.9 | 17.1 | 22.6 |

| No. of responden | ts 69 | 69 | 29 | 31 |

| Source: The World Bank, “Central Banks Reserve Management Practices: Insights into Public Asset Management” (October 22, 2021). | ||||

These results are consistent with the standard non-contingent framework of most central banks, where the duration decision only balances the trade-off between a higher expected return and a higher volatility of such expected return (ie, a higher return-at-risk). However, reserve portfolios are subject to stochastic processes, where changes in the market value of the financial assets portfolio are usually less significant than the changes that could be caused by the volatility of capital flows.77 As shown in Caballero and Panageas (2004), there is a hedgeable component and this hedgeable component is significant.

Once these changes are included in the calculation of the volatility of a reserves portfolio, we can see that, when searching for higher yields, the decision to increase the duration of the reserves portfolio is one that goes in the right direction as it can help a central bank to reduce the country’s vulnerability to external shocks. Indeed, as noted above, during episodes of financial turmoil US Treasuries and other “safe” government bonds (eg, German Bunds) tend to rally. The longer the duration, the higher the gain, and this happens at a time when the probability of using the reserves increases, and therefore the marginal value of an extra unit of reserves also increases.

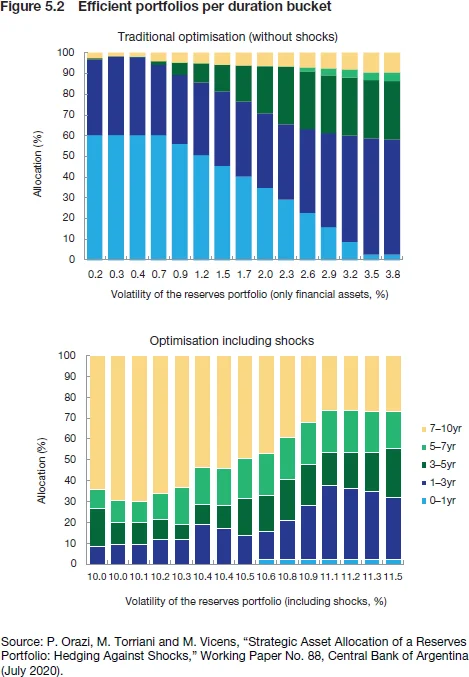

Furthermore, when the hedge decision prevails, there can be an important shift in the optimal duration suggested for the reserves portfolio, as the longer the duration, the better the hedge provided. Figure 5.2 shows the contrasting results that could be obtained in the construction of the efficient frontier of a reserves portfolio when including (or not including) the impact of external shocks in the calculation of the volatility of such a portfolio. If the optimisation were run under the traditional “no-shocks” approach, there would be small allocations to long-term government bonds due to the higher return-at-risk of such tenors. However, if the optimisation were run in a more comprehensive framework that included the impact of external shocks, the construction of the efficient frontier would tend to give more preference to hedge assets (ie, long-term bonds), and paradoxically the greater the weight of these assets in the portfolio, the lower the volatility of the reserves portfolio due to the hedge provided.88 See Orazi, Torriani and Vicens (2020).

Therefore, when the duration decision is analysed under a more comprehensive framework (ie, the contingent one), the benefit of having a longer duration starts to play a key role, helping a central bank to find their compensation for increasing the return-at-risk in the financial assets portfolio, even in times with a low term premium as we have seen recently.

Credit risk can increase the procyclicality of the reserves portfolio

Reserve managers have always been committed to government bonds: the mainstay of reserve management. However, in the search for higher yields it has become common practice to seek higher credit risk exposures through “diversification” into other assets classes such as corporates, mortgages, emerging market bonds and equities.99 See Carver and Pringle (2021), p. 1. Although actual allocations to these asset classes or strategies appear to remain very limited,1010 See World Bank (2021), p. 32. adding new asset classes in the light of continuing low yields is a persistent trend in reserve management.

How does this “diversification” into other assets classes work when reserves are most needed? Probably not very well. First, financial crises are often accompanied by drastic changes in the correlation structure of financial asset portfolios. Second, and more importantly, credit risk is procyclical. During episodes of financial turmoil there is a sharp increase in the funding challenges for private firms. The lower the credit rating, the greater the challenges faced. In those scenarios, central banks, which have safety as one of their most important investment pillars, will probably face some pressure to reduce their exposure to credit risk, which will only exacerbate the funding problems of such firms.1111 In J. Pihlman and H. van der Hoorn, “Procyclicality in Central Bank Reserve Management: Evidence from the Crisis,” IMF Working Paper No. 10/150 (2010), for example, we can see how the procyclical behaviour of central banks during the 2008–09 global financial crisis may ultimately have exacerbated the funding problems of the banking sector when they pulled around $500 billion of deposits and other investment from such sectors, which required offsetting measures by other central banks such as the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank.

Table 5.2 shows how some US dollar-denominated asset classes tend to move in tandem with a “synthetic” asset shock index that emulates the two most common sources of external vulnerability for Latin American countries: terms-of-trade and financial shocks.

| Asset class | 1–3yr | 3–5yr | 5–7yr | 7–10yr |

| US Treasuries | -0.06% | -0.13% | -0.16% | -0.20% |

| US Agencies | -0.05% | -0.08% | -0.10% | -0.11% |

| US Corp AAA | 0.00% | -0.01% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| US Corp AA | 0.02% | 0.03% | 0.07% | 0.09% |

| US Corp A | 0.11% | 0.13% | 0.18% | 0.18% |

| US Corp BBB | 0.16% | 0.21% | 0.31% | 0.34% |

| US Supras AAA | -0.03% | -0.03% | 0.00% | 0.03% |

| US MBS | -0.01% | -0.02% | -0.02% | -0.13% |

| US TIPS | 0.14% | 0.16% | 0.16% | 0.17% |

| Source: Orazi, Torriani & Vicens (2020). | ||||

As expected, the typical safe-haven assets (US Treasuries) have a negative covariance with the asset shock index. This means that they will perform well when reserves are most needed, acting as a buffer to mitigate the impact of external shocks. In contrast, US corporates below AAA ratings have a positive covariance with the asset shock index. The lower the credit rating the higher the covariance, which means they will likely increase the challenges faced by a central bank at a time when the reserves are most needed.

From this perspective, the search for higher yields through an increase in the exposure to credit risk does not seem a decision consistent with the primary objective for holding reserves (ie, the self-insurance against external shocks). Furthermore, it appears to be a decision that may create a conflict of interest between a reserve manager’s mandate to safeguard the security of the reserves and the central bank’s mandate to safeguard financial stability during episodes of financial turmoil. This is especially true if the individual decisions of reserve managers across central banks are considered together.

So does this mean there is no possibility to consider enhancing returns? No. To maintain consistency between reserve investment strategies and the countercyclical type of reserve portfolios that central banks should construct to complement their macroprudential policies and safeguard financial stability, the search for higher yields through higher credit risk exposures should be carefully considered by central banks, and should preferably be taken as a short-term tactical allocation rather than a long-term strategic one. This is the case unless there is certainty that those higher exposures will remain in the portfolio “through-the-cycle”, and there is no risk of liquidating or reducing such positions during episodes of financial turmoil.

The remainder of this chapter considers some suggestions to that end, beginning with currencies.

Currency clusters are key to understanding the true diversification benefits

While the US dollar and euro have remained the most important currencies in the composition of reserve portfolios, there has also been a growing trend to expand eligibility and exposure to other currencies.1212 See, for example, HSBC Reserve Management Trends (2020; 2021) and “RAMP Survey” (2020; 2021). “Diversification” is commonly regarded as the reason behind such behaviour. Although there is no common framework among central banks to define the currency composition of a reserves portfolio, central banks often divide reserves portfolios into a “liquidity tranche” designed to finance their day-to-day FX needs and an “investment portfolio” that seeks to obtain the highest return subject to risk constraints. The larger the relative size of the liquidity tranche, the more important the effect of some balance of payments components is in defining the currency composition of the reserves portfolio. Conversely, the larger the relative size of the investment tranche, the larger the effect of reserve currencies’ expected returns on the currency composition of the reserves.1313 Y. Lu and Y. Wang, “Determinants of Currency Composition of Reserves: A Portfolio Theory Approach with an Application to RMB,” IMF Working Paper No. 19/52 (2019).

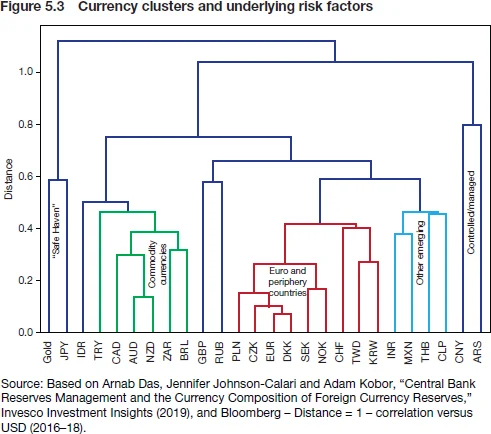

Under the traditional non-contingent reserve management framework, “diversification” into other reserve currencies mostly focuses on diversifying the currencies’ expected returns based on the currency used to report performance, also known as the “numeraire”. As a result, currency risk depends mainly on the definition of the numeraire. However, from a country risk management perspective, it is much more important to understand how “diversification” works in relation to a country’s own macroeconomic risk factors rather than diversifying the correlation among currency returns. There are currency groups that tend to move in tandem, and with other factors such as region, commodities or “flight to safety” during periods of heightened market volatility (see Figure 5.3).1414 As shown in Arnab Das, Jennifer Johnson-Calari and Adam Kobor, “Central Bank Reserves Management and the Currency Composition of Foreign Currency Reserves,” Invesco Investment Insights (2019).

From this perspective, the decision to “diversify” into other reserve currencies should carefully consider the underlying risk factors that are very specific to each country or region. The decision to “diversify” into other emerging market currencies could, for instance, end up with the same conclusions for both a developed and an emerging market country if only viewed from a portfolio management perspective. However, from a country risk management perspective, only the developed country would actually be diversifying macroeconomic risks. The emerging market country would likely be diversifying currency returns at the expense of exacerbating its vulnerability to external shocks, as most emerging market currencies tend to depreciate against the US dollar during episodes of financial turmoil.

Table 5.3 shows how the synthetic asset shock index mentioned above correlates with the traditional ICE-Bank of America Merrill Lynch government bond Indexes. If currency exposure were fully hedged to the US dollar, investing a reserve portfolio in most of these government bond indexes would likely help to reduce the vulnerability to external shocks. In fact, the US dollar tends to appreciate during episodes of global financial turmoil. In addition, these episodes typically lead to an increased probability of monetary policy easing by major central banks, pushing yields lower and increasing the market value of these financial assets.

Conversely, if currency exposure were not hedged to the US dollar, vulnerability to external shocks could be exacerbated. Indeed, the most contrasting results are observed in the case of commodity currencies such as the Australian or Canadian dollars since the exposure to commodity prices is usually very high for most emerging market countries (including Latin America).

Therefore, reserve managers should carefully consider the underlying risk factors that are very specific to each country or region before taking the decision to “diversify” into other reserve currencies, as their reserve management decisions can impact the country’s vulnerability to external shocks.

The breakdown of covered interest rate parity creates opportunities

Anyone who studied finance in college will recall that covered interest rate parity was an unbreakable law. The interest rate differential between two currencies in the money markets should always equal the differential between the forward and spot exchange rates. Otherwise, arbitrageurs could make a seemingly risk-free profit. However, since the global financial crisis of 2008–09, covered interest rate parity has failed to hold and the interest rate differential for lending US dollars against some currencies, notably the euro and yen, has created interesting opportunities for institutional investors such as central banks.1515 See, for example, C. Borio, R. McCauley, P. McGuire and V. Sushko, “Covered Interest Parity Lost: Understanding the Cross-currency Basis,” BIS Quarterly Review (September 2016) to understand the factors driving the persistence of a cross-currency basis.

| Unhedged | 100% hedged to USD | ||||||||

| Govies/term | Currency | 1–3 yr | 3–5 yr | 5–7 yr | 7–10 yr | 1–3 yr | 3–5 yr | 5–7 yr | 7–10 yr |

| United States | USD | –0.42 | –0.40 | –0.38 | –0.38 | ||||

| Germany | EUR | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.08 | –0.31 | –0.33 | –0.35 | –0.35 |

| France | EUR | 0.21 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.10 | –0.26 | –0.29 | –0.31 | –0.30 |

| Italy | EUR | 0.18 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.09 | –0.20 | –0.19 | –0.20 | –0.20 |

| Spain | EUR | 0.18 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.07 | –0.24 | –0.27 | –0.26 | –0.26 |

| Japan | JPY | 0.18 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 0.10 | –0.05 | –0.27 | –0.33 | –0.34 |

| United Kingdom | GBP | 0.32 | 0.27 | 0.21 | 0.17 | –0.30 | –0.34 | –0.37 | –0.34 |

| Canada | CAD | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.69 | 0.65 | –0.23 | –0.28 | –0.26 | –0.23 |

| Australia | AUD | 0.63 | 0.58 | 0.55 | 0.51 | –0.51 | –0.54 | –0.51 | –0.46 |

| Sweden | SEK | 0.41 | 0.37 | 0.58 | 0.30 | –0.15 | –0.27 | –0.28 | –0.31 |

| Switzerland | CHF | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.01 | –0.03 | –0.36 | –0.36 | –0.35 | –0.36 |

| India | INR | 0.47 | 0.38 | 0.34 | 0.25 | –0.10 | –0.17 | –0.14 | –0.21 |

| China | CNY | –0.31 | –0.37 | –0.35 | –0.35 | –0.25 | –0.28 | –0.24 | –0.25 |

| Source: P. Orazi, M. Torriani and M. Vicens, “Strategic Asset Allocation of a Reserves Portfolio: Hedging Against Shocks,” Working Paper No. 88, Central Bank of Argentina (July 2020). | |||||||||

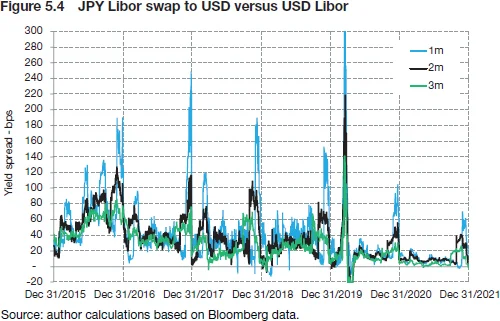

Indeed, when the shortage of US dollar funding in foreign exchange markets increases, the difference between the US dollar interest rate in the money market and the implied US dollar interest rate in the FX swap market (ie, the FX swap basis) increases, creating opportunities for reserve managers to supply US dollars against other currencies through these markets, as if they were placing synthetic deposits in US dollars but with the benefit of higher yields, more liquidity and probably less exposure to credit risk than traditional commercial bank deposits.1616 These strategies imply a higher exposure to one of the most liquid markets (FX markets), and for those central banks that have cash accounts in other central banks and ISDA agreements, with credit support annex (CSA) and daily variation margins, the additional risk for the reserve portfolio is likely limited to the credit risk of the daily change in the market value of the derivatives position, which is certainly less than the credit risk of a deposit with a commercial bank. For example, Figure 5.4 shows the yield spread in JPY Libor rates swapped to US dollars vs USD Libor rates. Although the basis has been narrowing in recent years, probably helped by the deployment of central bank swap lines, it tends to increase in quarter-end periods and during episodes of financial turmoil, as happened at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic.

When searching for higher yields, these short-term strategies can really help central banks to increase expected returns. Furthermore, these are countercyclical strategies that can also help reduce the shortage of funding in US dollars, complementing central bank swap lines in their objective of safeguarding financial stability.

Conclusion

Reserve management strategies should be consistent with the primary objective of holding reserves (ie, self-insurance against external shocks). Even if reserve portfolios are tranched into two (or more) separate portfolios, the long-term “investment portfolio” always functions as a supplemental buffer to the short-term “liquidity portfolio”. Therefore, the investment strategies implemented for such an “investment portfolio” should not be considered from a “long-only” portfolio perspective, as they could end up being in some cases inconsistent with the primary objective for holding reserves.

In this sense, one paper1717 G. Smith and J. Nugée, “The Changing Role of Central Bank Foreign Exchange Reserves”, OMFIF (September 2015). concluded that over the years central bankers have found that, when market sentiment turns negative, the only correct answer to “How much reserves do we need?” is “More”! Along the same lines, another paper1818 R. McCauley and J. Rigaudy, “Managing Foreign Exchange Reserves in the Crisis and After,” BIS Papers, 58, pp. 19–47; chapters in Joachim Coche, Ken Nyholm and Gabriel Petre (eds), “Portfolio and Risk Management for Central Banks and Sovereign Wealth Funds,” (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011). shortly after the global financial crisis of 2008–09 highlighted that those events, which posed a great challenge to all reserve managers, brutally reminded them of the original raison d’être of foreign exchange reserves: namely, to deal with emergencies.

When searching for higher yields, the implementation of longer duration strategies is consistent with the objective of increasing expected returns but also with the primary objective of holding reserves as they can help a central bank to hedge its country’s vulnerability to external shocks, increasing the market value of the reserves portfolio when reserves are most needed. Although, at the time of writing, April 2022, the outlook for longer duration strategies is very challenging, central banks should focus on the “buy-and-hold” strategies that they usually implement, and improve their communication policy to avoid short-term reputational damage.

Conversely, higher credit risk exposures would be more consistent with the primary objective of holding reserves if taken as a short-term tactical allocation, unless they can be maintained with no changes during episodes of financial turmoil (but then, what is the purpose of maintaining those expensive reserves?) “Diversifying” into corporates or other assets classes can become a nightmare during episodes of global financial turmoil, as they can reduce the market value of the reserve portfolio when reserves are most needed, and can also create other problems for the central bank (eg, liquidity problems if there is a shortage of liquidity in the credit markets). Furthermore, they may create a conflict of interest between the mandate of individual reserve managers to safeguard the security of the reserve portfolio and the mandate of central banks to safeguard financial stability.

“Diversification” of currency risk exposures should also be considered in a more comprehensive framework, as the underlying risk factors of currency clusters can be much more important for the country risk management than currency returns.

Central banks are key players in safeguarding financial stability. They should always try to build portfolios that are countercyclical, or at least not prone to procyclical behaviour that could exacerbate market volatility. How should they escape from the low-yield environment? Through strategies that can help to hedge the country’s exposure to external shocks, or at least that are not inconsistent with the primary objective of holding reserves.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: subscriptions.centralbanking.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com test test test

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com test test test