Rethinking equity investing at the National Bank of Austria post-2020

Franz Partsch

Executive summary

Trends in reserve management: 2022 survey results

Interview: Gerardo García

Central bank digital currencies: 10 questions

Rethinking equity investing at the National Bank of Austria post-2020

How can reserve managers escape low yields – and stay true to their mandate?

Reserve managers weigh the risks amid the Ukraine crisis

Appendix 1: Survey questionnaire

Appendix 2: Survey responses and comments

Appendix 3: Reserve statistics

Equities are, in the main, relatively new to reserve management. They are not new to reserve managers, of course, as they have been analysing them as part of their work to better understand markets for decades, and also in some cases through their involvement with their central bank’s pension fund. That was the case in Austria, where we started to introduce equities into our pension funds at the National Bank of Austria around 25 years ago. Then, in the light of the 2008 crisis and with the need for further diversification, we introduced equities into our reserve portfolios. We gradually built these equity investments up from a very low proportion to around 5% of our holdings by the end of 2019.

Then came the Covid-19 pandemic of 2020. We learned a number of lessons from the crisis that followed, which led to a significant change in our investment strategy and, as a result, an increase in our equity holding. This chapter will discuss the change in our investment strategy, beginning with the motivation behind the decision. A second section explores the case that was made to convince the board at the central bank to support the change, while a third section looks at how equity investment is made, in particular through the use of external managers. The chapter concludes with some remarks on the benefits that using exchange-traded funds (ETFs) can bring to reserve management.

Post-2008 investment

The major change in the investment process was implemented in May 2021, but it has its roots in the 2008 crisis. Indeed, the increase in equity holding we made last year, both in absolute terms but also as a share of the portfolio, was mostly a response to changes in the market conditions we have observed in recent years. From 2008 onwards we were faced with very low, or even negative, returns from traditional reserve assets, which are mainly fixed income assets, but also with significantly higher risk from monetary policy operations. In our view, equities were a good way to diversify from these two factors. This was unusual at the time for a central bank, it is fair to say, but not unheard of, and our motivation was clear.

The move into equity was also meant to be a response to the significantly higher risk of P&L losses for the central bank, as well as the higher return volatility we observed. However, there was also an unintended consequence – we found that, as a result of this new allocation, we faced the risk of very broad cyclical investment behaviour with respect to the traditional reserve assets, and indeed suboptimal returns also. This realisation led us to make a major change in our strategic asset allocation in several aspects, but most importantly to move to a much higher equity exposure than we had before – from around 5% to more than 12%. We also diversified into other kind of risk premia on the FX side, and also on the duration side, but here I will focus on the equity exposure.

The shift was not a straightforward one, however. This was a long discussion with our board at the central bank because this change would really mark a significant shift not only in our investment processes, but also to our strategic asset allocation. Such a change is not to be taken lightly and does not usually sit easily with central bank boards. How did we manage to convince them? The next section will outline the three elements we used to convince the board to let us increase the equity exposure in the asset allocation.

Convincing the board

The first was to present what we termed a “do nothing”, or “leave it as it is”, scenario (see backtesting results in Table 4.1). For conservative institutions, as central banks can often be, it is not unfair to say that such an option tends to be the preferred one. However, this was not a good option with respect to our return expectations, as Table 4.1 shows. Indeed, we calculated the “do nothing” option would deliver not just a very low return, but a fairly high risk of return as well. We therefore wanted to present some different options, and found reasonable alternatives that gave us much higher return prospects with lower relative risk, or perhaps not much higher relative risk.

Nevertheless, while a higher return expectation makes a very convincing argument, one has to be very clear about the possible negative events that could occur over time. It is well known that equity returns, although higher than fixed income returns over time, tend also to be more volatile. This affects not just the portfolio, of course, but the central bank’s balance sheet and P&L (see Table 4.2). Such attributes do not typically sit comfortably with central bank portfolios. The second element we presented was therefore a very clear view on how negative events could affect the P&L, and then that we had a correspondingly good plan on how to deal with these negative events. We also needed to know where our trigger points would be to review the strategy, and if need be to change it. In turn, this meant having a long-term perspective on what to do during times when returns are low or even negative, and what to do when returns are higher. Effectively, we had to show how we could use the balance sheet to smooth the effect of negative events over time. The last, but by no means least, element was a clear communication strategy on how to explain the strategy and potential consequences to stakeholders. Here, I should stress I don’t just mean internal stakeholders, notably the board, but also the shareholder or owner, which in our case is the Republic of Austria.

| % share in portfolio | ||||||

| Scenario | Gov. | Corp. | Equities | Return (%) | Risk div. (%) | Risk undiv. (%) |

| Base | 80.0 | 7.5 | 12.5 | 1.15 | 9.4 | 14.9 |

| Progressive | 67.5 | 7.5 | 25.0 | 1.80 | 12.0 | 20.1 |

| Aggressive | 45.0 | 7.5 | 47.5 | 3.00 | 19.6 | 31.4 |

| “Do nothing” | 83.3 | 9.7 | 7.0 | 0.89 | 9.7 | 14.2 |

| Source: National Bank of Austria. Note: "div." short for "diversified". | ||||||

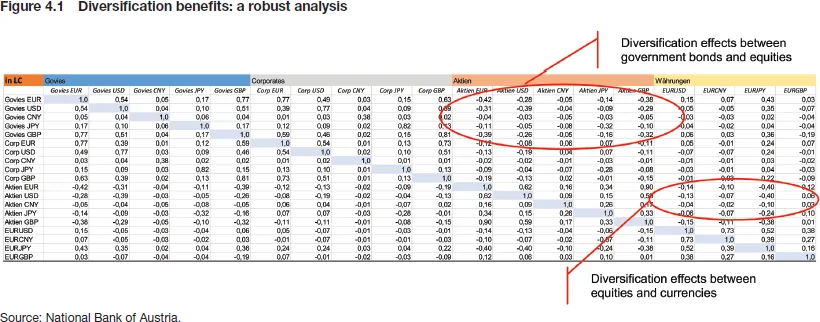

The third element was the need to have a very robust tool to analyse diversification effects (see Figure 4.1). This had to encompass different weights of equities in the portfolio construction, which in our case was mainly diversification effects between traditional assets such as equities and government bonds, but also on the foreign exchange side.

Equipped with this three-part brief, we were able to convince the board and our other stakeholders to increase the equity portfolio last year. Fortunately, we had a very good start in 2021, but 2022 will be a real test of whether the diversification strategy will play out as planned, and indeed will also be a check on how our stakeholders will respond to what will probably be a negative return in a year.

| Year | Government bonds (%) | Corporate bonds (%) | Equities (%) | Strategic asset allocation (%) |

| 2010 | 9.17 | 10.93 | 7.69 | 9.12 |

| 2011 | 9.17 | 6.11 | –9.84 | 6.57 |

| 2012 | 0.89 | 8.86 | 22.09 | 4.00 |

| 2013 | –3.79 | –1.49 | 23.79 | –0.17 |

| 2014 | 9.82 | 12.78 | 11.92 | 10.30 |

| 2015 | 5.83 | 3.90 | 10.83 | 6.31 |

| 2016 | 2.19 | 5.86 | 7.40 | 3.11 |

| 2017 | –4.98 | –1.10 | 10.07 | –2.81 |

| 2018 | 3.12 | 0.17 | –8.67 | 1.42 |

| 2019 | 3.58 | 10.06 | 27.69 | 7.08 |

| 2020 | –0.85 | 1.83 | 1.84 | –0.31 |

| Average | 3.10 | 5.26 | 9.53 | 4.06 |

| Volatility | 5.10 | 5.01 | 12.13 | 4.21 |

| Source: National Bank of Austria. | ||||

Equity investment: the case for external management

I now turn to the question of the best way to implement the strategy. First, I should say that the National Bank of Austria is a mid-sized or small central bank with limited research capacity and also limited numbers of staff. These factors necessarily influence our decision. As a result, from the start of our equity journey we used externally managers exclusively to manage our equity portfolios. This has turned out to be a very successful strategy. We have found that external managers (and ETFs in turn) give us the option to have very cost-efficient access to what were (and to some extent remain) “nontraditional” asset classes. We have found that there is a lot of competition between asset managers, which is only to the good from a client’s perspective, and it is noteworthy that if you are a central bank, you are perhaps viewed as an attractive client in some respects.

A further benefit of this strategy of external management has been that it enhances the market information we have because we diversify our external managers. In total we have around 40 managers across our portfolio, which gives us a very good overview of the market without having to invest too much in our own research capabilities.

A final advantage is that external management gives you only indirect exposure to equities and its issuers, as well as the associated actions and instruments that accompany share ownership. In particular, exercising voting rights can sometimes be a bit difficult or awkward for a central bank, and using external managers has meant we are indirectly involved in corporate actions and the like.

When you outsource equity management it is vital that you have a very streamlined and focused selection and monitoring process. This we have developed over time, and we also learned a great deal along the way about how to select managers, what the important factors are in selecting the right managers, and how to select managers that will implement the strategy in a professional way. I would stress, in particular, that this means that they should have good risk management capacity and effective reporting capacity. As a result, we put considerable emphasis on these elements during the selection process, and also to formalise our selection decisions.

It goes without saying that one should have a strict monitoring process. On the one hand, this helps ensure that the strategy is implemented in the way you plan over time, but on the other hand it means you can assess the performance of the managers. Then, if performance is not in line with expectations, there is a process of regularly changing managers and selecting new ones. And ETFs can play an important role here. When we change managers and would like to transfer funds between the two mandates, ETFs are a convenient way to do this while maintaining an exposure. They are also useful in their own right, notably when entering new markets or smaller market segments, or to implement tactical positions by going in and out of markets in a quicker way.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: subscriptions.centralbanking.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com test test test

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com test test test