Developing a sovereign ALM framework: a case study of Mauritius

Streevarsen P Narrainen

Executive summary

Trends in reserve management: 2020 survey results

Interview: Ma. Ramona Santiago

Scoring climate risks: which countries are the most resilient?

A hundred ways to skin a cat – or some practical thoughts on benchmark replication

Developing a sovereign ALM framework: a case study of Mauritius

Developing an integrated information system for reserve management: the experience of Peru

Appendix 1: Survey questionnaire

Appendix 2: Survey responses and comments

Appendix 3: Reserve statistics

Mauritius is an island in the south-west Indian Ocean with a population of around 1.26m. It is an upper middle income country with a per capita income of some $12,050,11 As computed by the World Bank, the income per capita for Mauritius was $12,050 in 2018, compared to the high-income benchmark of $12,375 for the same year. and is about to join the league of high income nations. Since the early 1970s, Mauritius has been diversifying its economy to reduce its high dependence on agriculture, in particular on the production and export of sugar, which then accounted for the bulk of GDP and export earnings. There are now some 15 different economic sectors contributing to the country’s GDP, including well-entrenched manufacturing and services activities. The tertiary sector, comprising tourism and financial services, among others, currently accounts for some 77% of GDP, while the secondary and primary sectors’ contributions represent,19% and 4%, respectively. Mauritius has pushed its economy towards the concept of “industry 4.0”, pursuing efforts to become a regional financial technology (fintech) hub, scaling up its import substitution industrialisation policy with a focus on the production of food and energy from local renewable sources, and expanding its economic space through the development of the “ocean economy” and its new Africa Strategy.

During this economic transformation, Mauritius has accumulated a significant amount of sovereign assets and liabilities. As of 2020, it has foreign currency reserves equivalent to some 13 months of import cover, compared to a low of 1.6 months in 1980. Pension funds have also been rising significantly, and the sovereign assets are now many times higher than they were in 1980. These include the net assets of the National Pension Fund (NPF), the foreign currency reserves at the Bank of Mauritius (central bank), the equity holding of the State Investment Corporation (SIC), fiscal revenues, and the value of land owned by government, among others. Liabilities have followed the same rising trend, be they government expenditure, the monetary liabilities of the central bank or public sector debt. Sovereign net wealth has also been expanding.

The sovereign balance sheet22 A sovereign balance sheet was first published in Mauritius in 2008, and work is ongoing to produce a fully-fledged balance sheet. of Mauritius has changed a great deal, both quantitatively with an increase in assets and liabilities and qualitatively in terms of diversity and sophistication, making the need to manage the balance sheet from a risk mitigation perspective evident and urgent. Moreover, there is some unease in government that the costs and risks associated with the liabilities are given much attention, while the sizeable accumulation of assets and the returns they generate are less talked about. This asymmetry results in an obvious bias in assessing and interpreting risks. There is thus a tendency to underestimate the sustainability of public sector debt and other liabilities, especially in a country where the bulk of public sector borrowing is used for investment in crucial public sector projects that are expected to generate higher economic growth in the future.

The government therefore decided it must move beyond debt and deficit metrics, and take a more comprehensive view of sovereign assets and liabilities. In June 2019 it announced in the budget speech that, as part of reforms in the public sector, it will implement an asset liability management (ALM) strategy. This will mean shifting from the current “silo” approach to a broader “portfolio” approach in the management of sovereign risks, with the intention of improving coordination between the various bodies that hold and manage sovereign assets and liabilities. This also requires the development of the country’s balance sheet, and the process for developing a sovereign ALM (SALM) framework for Mauritius has been launched and, as of March 2020, is ongoing.

The objective of this chapter is to elaborate on the SALM approach, how it can bring improvement to the management of sovereign assets and liabilities, the various steps that Mauritius is planning to develop the SALM framework, and the setting up of the Mauritius National Investment Authority (MNIA) to invest the main assets of the nation.

The chapter is organised as follows: the first section elaborates on the SALM framework and reviews the experience of a few countries that are currently establishing or have already established such a framework. The next section explains the rationale for Mauritius to set up a SALM framework, and the various models that are being considered. It must be emphasised that Mauritius has not yet decided on which model to adopt. The third section provides an account of the various portfolios of assets that are being managed, and the overall reforms the Mauritian government is considering regarding the management of sovereign assets and liabilities, including the establishment of the MNIA. A final section provides some concluding remarks.

The SALM framework and the experience of other countries

The central purpose of a SALM framework is for a country to be able to better identify and manage the financial risk exposures of the public sector as a whole, and to achieve greater financial and economic stability. To this end, the SALM framework combines the main assets and liabilities of the public sector in an integrated balance sheet to achieve coordinated management of the various risks – from a portfolio perspective. Having a balance sheet also provides essential information on assets and liabilities, and the net worth in both stock and cashflows terms. There is a widely held view in the literature that separate management of these assets and liabilities is suboptimal. One paper33 Hans J. Blommestein and Fatos Koc Kalkan, 2008. “Sovereign Assets and Liabilities Management : Practical Steps Towards Integrated Risk Management,” Financieel Forum/Bank-EN Financiewezen, World Bank: 360–69. argued that “it is suboptimal for sovereigns to manage their balance sheet via non-integrated risk view”, while the IMF44 International Monetary Fund, “Sovereign Asset?Liability Management – Guidance for Resource-Rich Economies” (June 11, 2014). put it even more emphatically: “From the risk–return perspective, it is suboptimal to optimise isolated balance sheets rather than the consolidated sovereign balance sheet.”

Banks provide the most prominent example of the application of an ALM approach. They must carefully manage their assets and liabilities as one overall portfolio, since the structure, sources, duration and other characteristics of liabilities impact directly on decisions on how to invest the assets. Private enterprises use the ALM approach to reduce risks and to maximise their profit. However, the primary objective of the ALM approach in the public sector is not to maximise the country’s net worth but to better manage the risks to financial and economic stability, and also to promote long-term economic development. The objective function of SALM cannot be the same as the traditional risk/return optimisation principles of portfolio allocation for the simple reason that some assets may be considered as public goods (a prominent example being foreign currency reserves). Moreover, a country’s assets and liabilities are not as easily identified and quantified as those of banks and other private enterprises. These realities make the integrated portfolio approach to SALM more complicated but do not undermine its superiority over the silo approach.

Any risks to the sovereign assets and liabilities that can compromise a country’s long-term economic growth and development must be carefully monitored and managed, bearing in mind that most risks cannot be eliminated but can be reduced and their impact mitigated. For example, risks resulting from a change in the exchange rate of a country’s currency, or from fluctuations in interest rates, can be mitigated by better matching of assets and liabilities in terms of amount, maturity and currency composition, among others. A similar rationale applies for risks that can result from structural changes and imbalances, such as ageing of the population, a financial crisis or major contingent liabilities realisation leading to bailouts of state-owned and other corporates. By adopting a holistic portfolio approach in an ALM framework, these types of risks can be greatly reduced.

Selecting the SALM approach

The first step to developing a SALM framework is to get the approach right from the very beginning. Few countries, if any, have developed a fully-fledged sovereign balance sheet. There seems to be consensus among researchers in the field on how complicated it is to construct a complete SALM framework. While it is most beneficial to incorporate a complete SALM framework for managing assets and liabilities, the process can be significantly simplified by starting with a conceptual framework. For example, by simply holding assets and debt instruments in the same currency, the effect of fluctuations in exchange rate may be completely offset.

The SALM conceptual framework does not require quantifying all risks but an understanding of how particular risks will impact both assets and liabilities. The country can also choose to start with a conceptual framework and aim to produce a complete balance sheet in the future. In between the simple conceptual and the complete balance sheet approaches, there are a number of other constructs of the SALM framework that a country can opt for. There is no universally agreed upon SALM framework – each country must choose the framework that best suits its needs. This point was made very implicitly in one country survey55 Mehmet Coskun Cangoz, Sebastien Boitreaud and Christopher Benjamin Dychala, “How do Countries Use an Asset and Liability Management Approach? A Survey on Sovereign Balance Sheet Management,” Policy Research working paper no. WPS 8624, World Bank Group (October 2018) surveyed 28 countries that have set up a SALM framework. It offers a wide spectrum of existing SALM models that can help inspire new SALM frameworks in other countries. that showed such frameworks have been implemented for many different reasons, and with different objectives and priorities.

Constructing the sovereign balance sheet

Once the approach to introducing the SALM framework is decided, constructing the appropriate balance sheet becomes the next logical step. For some countries, a significant part of their assets can be non-financial physical assets that need to be identified and evaluated. There can also be off-balance sheet items that can complicate the task even further. The checklist for constructing a sovereign balance sheet can be quite extensive, which is why the choice of SALM approach – and its definitions and objectives – must be set out very clearly and with ample detail so that the appropriate assets and liabilities are included in the balance sheet.

Integrating risk management

Having a sovereign balance sheet is a necessary but not sufficient step in the establishment of a SALM framework. The third vital step is the integration of risk management into the framework. The financial and risk characteristics of the assets and liabilities must be fully understood so that there can be active management and a quick response to minimise risk. It has been pointed out that:66 Udaibir S. Das, Yinqiu Lu, Michael G. Papaioannou and Iva Petrova, “Sovereign Risk and Asset and Liability Management: Conceptual Issues,” IMF Working Paper 12/241, International Monetary Fund (4 October 2012).

As the SALM objectives are frequently specified based on a narrow set of the balance sheet items, the risk management considerations from an asset management perspective naturally involve minimising liquidity and credit risk and, in some cases, interest rate risk. From a liability management perspective, considerations for minimising interest rate risk, refinancing risk, and currency risk prevail among debt managers.

The importance of the sovereign in making the decision on whether it will develop a centralised or decentralised risk management framework has also been stressed:77 Elizabeth Currie and Antonio Velandia, “Risk Management of Contingent Liabilities Within a Sovereign Asset-Liability Framework, World Bank (2002).

The degree of risk management centralisation, both in policy and organisational terms, may depend on the macroeconomic context, on risk tolerance and risk management capacity, and on the type of institutional and political arrangements, such as the degree of political decentralisation, etc. The more vulnerable the sovereign is to shocks and the weaker its risk management capacity, as well as that of the rest of the public sector and indeed the private sector, the more stringent central government guidelines and monitoring should be. This is particularly important with regards to contingent liabilities (CL), which are often hidden and unaccounted for. The central government may end up not only monitoring and managing balance sheet risks, but also promoting a risk management culture in the rest of the public sector.

Establishing effective coordination and a SALM governance structure

While an ALM framework enables the government to have a better oversight of its sovereign balance sheet, the management of the various components would still be the responsibility of separate institutions – for example, a debt management department for the management of government debt, the central bank for the management of the country’s foreign currency reserves, and still another institution for the investment of the pension funds. These institutions and departments have different mandates, and operate under specific legal and regulatory framework and constraints. To combine them to operate in an overarching SALM framework is a major challenge. The fourth step is therefore to establish an effective coordination of the strategies and policies of the various institutions, and set a strong SALM governance structure.

Experience of countries with SALM

Since the 1990s, most countries around the world have seen their assets and liabilities rise at a rapid pace. Globally, foreign currency reserves have surged both in terms of absolute amount and relative to GDP. There has also been an equally significant increase in liabilities. Government and public sector debt have soared. The sheer size of current national balance sheets has compelled many countries to review their approach to managing their sovereign assets and liabilities.

As countries’ assets and liabilities were expanding, a number of global financial events88 The recent Covid-19 event may be yet another justification for the development of a SALM framework. For many countries, the adverse impact of Covid-19 would be significant on both stocks and flows on both sides of the sovereign balance sheet. Having a sovereign balance sheet would greatly enhance a country’s effectiveness in mitigating the risks. have set the spotlight on balance sheet weaknesses. One commentator has said:99 Fatos Koc, “Sovereign Asset and Liability Management Framework for DMOs: What do Country Experiences Suggest?” UNCTAD (January 2014).

The capital account crises that struck a number of emerging economies in the 1990s showed the importance of currency and maturity mismatches between sovereign assets and liabilities. In Mexico (1994), Brazil (1999) and Russia (1998), the crises were mainly caused by government high foreign currency denominated debt vis-à-vis low foreign reserves. Moreover, high levels of short-term debt (Mexico (1994) and Turkey (2001)) and floating rate debt (Brazil 1999) have increased the vulnerability of sovereign balance sheets to external shocks.

The global financial crisis of 2008 was another addition to the list of adverse financial events. As a result, a number of countries have responded by developing a SALM framework to better assess and mitigate the risks to their national balance sheets. For example, Canada manages its foreign currency assets within an ALM framework to reduce risk. New Zealand has a Balance Sheet Risk Management (B-Risk) programme that offers a holistic approach to managing sovereign balance-sheet risks and opportunities to minimise vulnerabilities to external economic shocks. Uruguay is also applying a SALM approach to better manage its currency exposure in its balance sheet, and to assess and mitigate the associated risks on the economy. The main objective of the Uruguay government is to reduce vulnerability to shocks at the aggregate level while improving efficiency.

It is clear that ALM practices and objectives vary from country to country. It is also manifest that the application of SALM principles does not require a complete and comprehensive balance sheet – they can be applied to “sub-portfolios”. There are examples of such approaches in Canada, Turkey, Sweden and the UK, among others, where the currency composition of public debt and international reserves may be matched through coordination between debt and reserve management.

Rationale and models under consideration

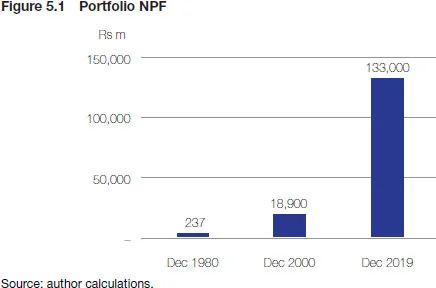

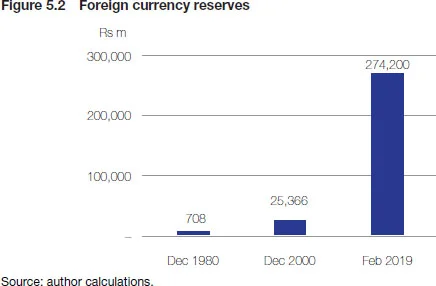

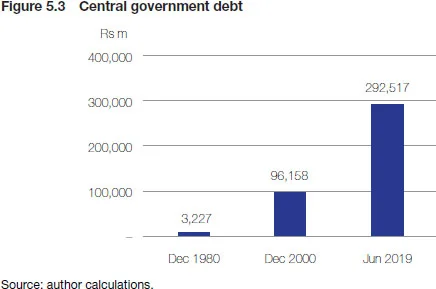

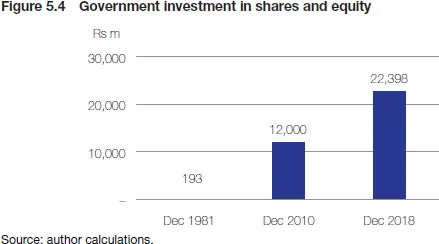

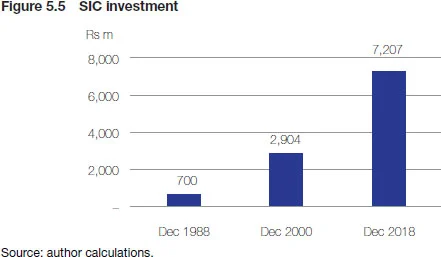

The case for Mauritius to set up an ALM framework is compelling. In the past four decades, the country has built up a considerable amount of both assets and liabilities. The balance sheets of the government and various governmental institutions (parastatal bodies and state-owned enterprises, SOEs) have continuously expanded as a result of sustained economic growth. As illustrated in Figures 5.1–5.4, the government’s investment in shares and other equity grew from MRs193m in 1980 to around MRs22 billion by end-June 2018.1010 MRs are the Mauritius currency of rupees. The country’s gross official foreign currency reserves, managed by the Bank of Mauritius, increased from MRs780m in 1980 to around MRs270 billion at the end of December 2019, and to MRs274 billion by end-February 2020. A large part of government investments is made through the SIC,1111 The SIC was established in 1984 to provide equity finance to both existing and new enterprises in all sectors of the economy, varying from small- and medium-sized enterprises to high-growth entrepreneurial ventures. which by the end of 2018 had accumulated an investment portfolio of some MRs7 billion compared to that of MRs700m in 1988. At December 2019, the NPF1212 The assets of the NPF are under the control of the government. The NPF is a contributory private sector pension plan, with defined contribution from employers and employees. The investments of the NPF are overseen by a tripartite investment committee comprising representatives of government, employers and employees. It is expected that the NPF will generate surplus funds until 2028. had an investment portfolio of MRs133 billion compared with MRs237m in 1980.

The central government debt, which is managed by a debt management unit at the Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development (MoFEPD), amounted to MRs3.2 billion in 1980 and increased to MRs326.5 billion at end-December 2019. At end-June 2019, government expenditure had amounted to some MRs136.6 billion against revenues of MRs121 billion. As the government has been actively involved in the economy through the establishment of a number of parastatal bodies and state-owned enterprises, it has also built up contingent liabilities.

In 2008, the Ministry of Finance published, for the first time, a balance sheet to provide a clearer picture of sovereign assets and liabilities. This exercise is still a work in progress. The latest balance sheet, which is not a complete one in terms of components and value, is shown in Table 5.1. Three items, namely, investment in “land and infrastructure”, “foreign currency reserves” and “fiscal revenues”1313 While the balance sheet should include the present value of government revenues and expenditures, this is not yet the case in Mauritius as it is still working on producing a more complete balance sheet. make up 92% of the total assets. Investment in land and infrastructure accounts for some 50% of the total assets. On the liabilities side, direct liabilities, of fiscal expenditures and the net market value of sovereign debt account for 95% of total liabilities.

Through a number of actions in recent years, Mauritius has unwittingly paved the way to a formal SALM framework. First, it has started work on the development of a sovereign balance sheet, with the primary objective of monitoring the overall financial position of the government and to determine the sovereign net worth. The development of a SALM framework was not one of the objectives. Although there is no comprehensive sovereign balance sheet yet, Table 5.1 provides a fairly good conceptual portfolio of assets and liabilities. However, there is still a significant amount of work to be done to identify and value the land and other physical properties of the government, both locally and abroad. Mauritius is facing many of the same challenges that other countries have experienced, including the availability of data, choosing the right valuation methodologies, the complexity of the legal structure and governance arrangements between central government and other public sector entities, as well as differences in accounting principles and standards across the public sector.1414 See Cangoz et al (see note 5). The difficulties in producing the sovereign balance sheet are compounded by the fact that the government of Mauritius is now gradually shifting to accrual accounting from cash accounting.

| Assets | MRs (m) | Liabilities | MRs (m) |

| Fiscal revenues | 128,686 | Direct liabilities | |

| Foreign exchange reserves | 267,917 | Fiscal expenditures | 146,520 |

| Marketable securities (SIC) | 7,548 | Net market value of sovereign debt | 301,365 |

| Onlending | 14,319 | Other payables (interest on debt, pensions, | 141,414 |

| sick leave, vacation leave) | |||

| Investments in SOEs | 24,753 | ||

| Investment in land & infrastructure | 465,867 | Contingent liabilities | |

| IMF SDR deposit and reserve tranche | 4,736 | Explicit contingent liabilities | 27,417 |

| Cash and bank balances | Implicit contingent liabilities | ||

| Total assets | 929,218 | Total liabilities | 616,753 |

| Equity | |||

| Net worth of government estate | 312,465 | ||

| Source: MoFEPD. Note: The Mauritius rupee/dollar exchange rate used was about MRs37/$1. The balance sheet is based on the model in Currie and Velandia (2002), see note 7. | |||

The second set of actions taken relate to coordination mechanisms on policies that have both a direct and indirect impact on the main assets and liabilities of the government. There is a macroeconomic coordination committee at the MoFEPD, comprising its Economic Research and Planning Bureau, its Debt Management Unit, the Bank of Mauritius, the Financial Services Commission, the Economic Development Board and Statistics Mauritius, to coordinate policies and actions that affect the economy. On many occasions that committee has thrashed out issues that can have a direct impact on the sovereign balance sheet – issues ranging from the persistence of high excess liquidity in the banking system to the impact of flows from the global business sector on the country’s balance of payments and on official foreign currency reserves. There is also coordination between the Debt Management Office, the Accountant General Office and the Bank of Mauritius on the amount, type and timing of debt instruments to be issued by government to ensure a smooth functioning of the government debt market. In addition, the minister of finance chairs a high-level Financial Stability Committee that comprises the minister for financial services, the governor of the Bank of Mauritius, the chief executive officer (CEO) of the Financial Services Commission, the managing director of the Financial Intelligence Unit and the financial secretary as members.

A third action, taken in December 2019 by the government and the Bank of Mauritius, was the transfer MRs18 billion from the realised gains made in the revaluation of its foreign currencies to prepay foreign currency debts. The rationale for doing this was very much in line with SALM principles – using assets that are not yielding much to prepay liabilities that are costing a lot. These three sets of actions are not being implemented within a formal SALM framework, but they do show that Mauritius has, unintentionally, been setting the stage for a formal SALM framework. It must now choose the appropriate model and establish an effective governance structure for implementing the ALM approach.

Mauritius will need to set out formal, strong and effective mechanisms for coordination at the MoFEPD to deal with the issue of fragmentation in the operational management of sovereign assets and liabilities. All the different players and stakeholders must be conscious that they have to operate within a well-defined SALM framework, and the MoFEPD will have to decide on what shape the governance arrangements for the implementation of the SALM framework will take.

For a SALM framework to be effectively implemented it is important there is a high level of institutional coordination between entities that control or manage sovereign financial assets and sovereign liabilities. Ideally, coordination should be given an appropriate legislative setting, as different institutional objectives and the required degree of coordination between the entities involved may lead to institutional frictions. In case institutional constraints render an integrated asset and liability management strategy impossible to implement, more feasible second-best options may take place.1515 See Das et al (see note 6). The governance structure will have to be strong and authoritative enough to address the challenge of coordination, communication and the exchange of information among the various institutions and bodies that have responsibility for managing specific sovereign assets and liabilities. This is work in progress at the MoFEPD.

Setting up the MNIA

At the same time that Mauritius is implementing a SALM framework, it is also setting up the MNIA. To this effect, a government bill is expected to be passed in 2020 at the National Assembly of Mauritius whose main objective will be to provide for the establishment of the MNIA, which shall take over the functions and powers of the NPF and the National Savings Fund (NSF)1616 The NSF provides for the payment of a lump sum to every employee on their retirement or at the time of their death. Investment Committee for the management and investment of the assets and surplus funds of the NPF and NSF. The bill will also ensure that the MNIA is responsible for the management and investment of:

-

-

funds vested in it by any statutory corporation, any government-owned corporation, any government-controlled corporation and such other bodies as may be prescribed; and

-

-

-

such other funds as may be prescribed.

-

As the MNIA takes over the portfolios of the NPF and NSF, and also of the Treasury Foreign Currency Management Fund (TFCMF), it will be responsible for the management of a portfolio of some $4.7 billion (see Table 5.2). The portfolio to be managed by the MNIA will consist of both domestic and external investments.

| Current | Asset portfolio ($ billion) | Future | Asset portfolio ($ billion) |

| NPF and NSF | 4.3 | MNIA | 4.7 |

| Investment | |||

| Committee | |||

| TFCMF | 0.4 | ||

| Investment in SOEs | 0.2 | Investment in SOEs | 0.2 |

| SIC | 0.7 | SIC | 0.7 |

| Foreign currency | 7.2 | Foreign currency | 7.2 |

| reserves (Bank of | reserves (Bank of | ||

| Mauritius) | Mauritius) | ||

| Total financial | 12.8 | 12.8 | |

| assets | |||

| Source: author calculations. | |||

The SIC will continue to operate as it does currently, with an investment portfolio of around $700m, mainly invested in equity. While the MNIA will seek to maximise returns on its portfolio for a given level of risks, the SIC will continue to invest to promote the development of new economic sectors. The SIC will maximise economic rather than financial returns, with a focus on investing in innovative businesses and supporting government policies on adapting to industry 4.0. In the same vein, it will be investing to promote import substitution and expand the country’s economic space through the ocean economy endeavour and its Africa Strategy.1717 One of the long-term development goals of Mauritius is to expand its economic space on both the demand and supply sides. On the demand side, this will be through an Africa Strategy. Africa has a market of some one billion consumers and there are increasing opportunities for investment by Mauritian businesses. On the supply side, the strategy will focus on harnessing the vast potential of its maritime “exclusive economic zone” of around 2.3m square kilometres. For further details on these strategies, see “Three Year Strategic Plan: 2017/18–2019/20” at mof.govmu.org.

Together, the MNIA and SIC will have a sovereign investment fund of some $5.4 billion, which could be the largest portfolio of assets in the country. Given the rather small size of the equity market in Mauritius and the lack of liquidity on the local stock exchange, an increasing share of the MNIA’s portfolio will have to be invested abroad. Potentially, the MNIA could also receive a mandate in the future for investing part or all of the country’s excess foreign currency reserves, which would bring the total portfolio under its management to between $8 billion and $10 billion.

Conclusions

The development of the SALM framework in Mauritius is on the right track. As the process continues, it is clear that Mauritius will need to have recourse to experts in the field to help produce an appropriate balance sheet, integrate risk assessment in the SALM framework and to set out an effective coordination mechanism.

Box 5.1 Lessons from the process

-

-

Since there is no-one-size-fits-all SALM framework, Mauritius has enough scope to tailor its SALM framework to its specificities.

-

-

-

The setting up of the framework will require a significant change in culture and attitude among the professionals who, up until now, have been managing assets and liabilities in silos.

-

-

-

Mauritius will require expert help in building its sovereign balance sheet – shifting from one focused on maximising the sovereign net worth to the management of sovereign risks within a SALM framework.

-

-

-

The coordination mechanism to be set up must be supported by strong political commitment and well-defined statutory powers to be effective.

-

-

-

Various legislations relating to the central bank, banks, debt management, pension funds, among others, will have to be revisited to accommodate the implementation of the SALM framework.

-

-

-

Moving forward on its SALM agenda, Mauritius will benefit from the vast and deep pool of expertise, knowledge and country experiences that have been built up in the field over the past two decades.

-

Some of the groundwork is already in progress. The government is producing a sovereign balance sheet, but encountering similar challenges that many countries have had to face or are facing – namely, identification of all the assets and their valuation. As the balance sheet is constructed, there will be decisions to take on what assets and liabilities are legally under the control of the sovereign. One such issue will definitely be the treatment given to foreign currency reserves.

There is already a set of policy coordination mechanisms at the MOFEPD that can be revisited, consolidated and formalised to become an integral part of the SALM framework. The recent decision to use part of reserve assets to prepay external debt and the forthcoming establishment of the MNIA to reform financial assets management demonstrates the commitment of the Mauritian Government to develop a strong SALM framework. It has not set a timeline for the completion of the SALM framework, but is determined to accelerate the process. It can therefore be expected that a SALM framework should be in operation by the end of 2021.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.centralbanking.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com