Reserve management: A governor’s eye view

Federico Sturzenegger

Foreword

The cashless society?

Executive summary

Trends in reserve management: 2019 survey results

Implementing a corporate bond portfolio: lessons learned at the NBP

Sovereigns and ESG: Is there value in virtue?

A methodology to measure and monitor liquidity risk in foreign reserves portfolios

Reserve management: A governor’s eye view

How Singapore manages its reserves

Appendix 1: Survey questionnaire

Appendix 2: Survey responses and comments

Appendix 3: Reserve statistics

Central bank reserve management has to deal with an ever-changing international scenario. Consider the events of 2018, for example. That year was the first in which the Fed pushed for balance-sheet normalisation and raised interest rates. In April of that year, it was common to share scenarios that anticipated many further hikes in interest rates. This scenario was mainstream and created significant change in the financing conditions in emerging economies. Fast forward to 2019, and you’ll find a Fed that suddenly pulls back (the result of Trump’s pressure?) and halts the anticipated rise in rates. Things move back to square one, yet with increased uncertainty now over long-term interest rates and inflation in the US. Nobody knows how these events will continue to unfold in 2019 and beyond.

This uncertainty is compounded by the fact that the US is increasing its budget deficit at a time of high expansion and record low unemployment. It seems all too natural to think that this will deteriorate its current account deficit. What will the consequences of that be? Will we see a full-fledged trade war in response? The world ahead of us, even when starting from a strong recovery, appears to be plagued by significant uncertainties.

In this dynamic world, one interesting topic to focus on for emerging economies is that of reserve management. In this chapter I would like to share with you some lessons I have learned from my tenure as governor of the Central Bank of Argentina. This issue seems to me particularly pressing given the uncertainties surrounding the scenario of monetary policy normalisation. International reserves are one of our best insurances against any possible volatility in capital markets, so “being prepared to navigate the policy normalisation” for Argentina means, at least partially, to smartly manage its reserves.

Therefore, I plan to do three things: review the macroeconomic context in which I had to make decisions about reserve management; review our discussion about the size of reserves; and, in more detail, discuss the composition of reserves.

Reserve management in context

Let me start with a review of the scenario I faced when making decisions on reserve management. As we took over from the previous government in December 2015, our international reserves were reaching very low levels. In fact, what we called net reserves – that is, our reserves net of our obligation in foreign currency – were negative. This was a difficult situation where we faced the challenge of lifting capital controls.

To make things worse, the previous government had sold US dollar futures for about the equivalent of a third of the monetary base at off-market prices. We not only inherited a very weak balance sheet at the central bank, but had a huge amount of liabilities maturing in the very short term. The context was also quite peculiar. President Macri had campaigned on the basis of lifting the exchange rate controls implemented in Argentina over the preceding four years. The parallel exchange rate on the black market was trading 1.5 times over the fixed official rate, so everybody was expecting a large depreciation of the official exchange rate. As a result, the transition between governments saw exports dwindling to zero, with boats moored side by side along the Paraná River waited for the unification of the exchange rate regime to occur before loading their products.

This situation called for swift action. We were convinced that a smooth opening of exchange rate controls was possible. Over the previous decade, Argentinians had done little else but hoard billions of foreign assets as a result of the lack of trust in their government. This meant that Argentina had an excess supply of foreign currency assets, not the opposite. Thus, we believed that the opening of exchange rate controls would be less traumatic than most people thought. In fact, when we implemented it a few days after taking office, the transition was very smooth. Almost immediately the exchange rate started to float, settling at an intermediate level between the previous official and black market rates. Exports normalised, boats were loaded with grains and off they went. And imports dwindled. Of course, during the period of exchange controls firms had imported as much as possible, even more than they needed in the short term, to profit from the unsustainable appreciated official exchange (if they could get hold of that foreign exchange, obviously). Both factors allowed the peso to strengthen in the immediate aftermath of exchange rate unification. This was considered a big initial success for the central bank and the Macri administration.

However, after this big step Argentina was still in default and had very limited access to international debt markets. So, the second big step was that of normalising Argentina´s relation with its creditors. This happened in April 2016 when it settled a dispute with hold-out creditors who had obtained a favourable sentence in the New York courts. This sentence had forced Argentina to pay pro rata to these hold-out creditors whenever paying its other debt, and had ended with the country defaulting on its entire stock of debt. With this conflict behind, capital flows normalised, but remained very small. Thus, a third and important change occurred at the beginning of 2017, when the government released the remaining capital controls (in particular, a four-month stay period for financial investments). After that, capital flows grew in size quite dramatically.

The resolution of the hold-out issue, plus the normalisation of capital flows, provided much more room to invest central bank reserves. In fact, during the default period, reserves could only be held at institutions that were immune from attachment by hold-outs. But this came at a cost in returns. As soon as we could diversify our investment opportunities and force competition for some of our assets, there was an important increase in returns. During the first two years, the Central Bank of Argentina was able to increase by 60 basis points (bp) the spread relative to US Treasuries in its US dollar-denominated portfolio.

Just to give you an idea of the income that a country misses when it stays in default, 60bp per year applied to a reserves’ portfolio with our size means a net present value (NPV) of around $7 billion.11 See Pablo Orazi and Mario L. Torriani, “Los Costos Ocultos de Permanecer en Default,” Central Bank of Argentina (August 15, 2017): https://ideasdepeso.com/2017/08/15/los-costos-ocultos-depermanecer-en-default/. As we continue to increase our reserves and returns, this amount could end up exceeding the $10 billion paid by the national government to reach an agreement with the hold-outs. In short, just the improved income at the central bank justified, on its own, the cost of an agreement with the hold-outs.

Determining optimal reserves

Now, let me move onto the second question. With the normalisation of the economy, expected sustainable growth, a floating exchange rate and ample room to invest our assets, we then tackled the question of what would be the optimal amount of reserves.

As two seasoned master craftsmen of reserve currency management wrote some time ago:

… central bankers have found that, when market sentiment turns negative, the only correct answer to ‘How much reserves do we need?’ is ‘more’ […]. Reserves are now supporting the foreign currency exposures of the whole economy, whether public or private, and whether contractual or contingent [...]. The list of responsibilities that are potentially covered by reserves is like a child’s wish list at Christmas.22 See Gary Smith and John Nugée, “The Changing Role of Central Bank Foreign Exchange Reserves,” Official Monetary and Financial Institution Forum (September 2015): https://www.omfif.org/media/1122865/jn-gs-report-master.pdf.

Over time, reserves were transformed from a financial exchange rate management tool to a creditworthiness confidence-building tool, performing a key role in the policy toolkit of most economies as they reduce the likelihood of balance of payments pressures.

In a 2011 paper,33 IMF, “Assessing Reserve Adequacy” (February 14, 2011): https://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2011/021411b.pdf. the IMF proposed different metrics to address the optimal level of reserves for precautionary purposes. Depending on the exchange rate regime chosen by each country, they said reserve adequacy should be at least 100–150% of a composite metric that covers three different kind of potential shocks: an external drain or sudden stop in external financing (both in fixed income and equity markets); an internal drain (ie, the risk of capital flight); and the potential loss that could arise from a drop in external demand or a terms of trade shock. They suggest the following coefficients for fixed and floating-rate exchange rate regimes.

-

-

Fixed: 30% of short-term debt + 15% of other portfolio liabilities + 10% of M2 + 10% of exports

-

-

-

Floating: 30% of short-term debt + 10% of other portfolio liabilities + 5% of M2 + 5% of exports

-

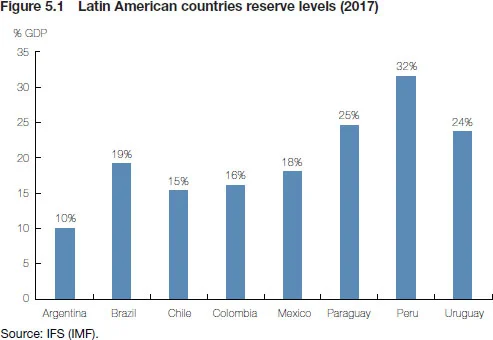

Nevertheless, these metrics do not appear to be strongly influencing countries’ actual reserve holdings. While, according to the IMF, the average range covered by the above methodology for emerging market countries is nearly 15% of GDP, we found that Latin American countries typically held a larger amount of reserves (see Figure 5.1 opposite).

In our case, as we were coming from a much lower level, we decided on 15% of GDP as our first objective in terms of reserves accumulation. As mentioned, that would just be enough to put us on a par with countries in the region with the lowest level of reserves. This made sense as a first stepping stone.

The combination of the need to accumulate reserves, plus the fact that the government had an excess supply of dollars as it was financing abroad its fiscal deficit, implied a natural agreement by which the central bank would buy these excess dollars to the Treasury, sterilising afterwards the pesos issued by issuing short-term central bank debt. As a result, reserves experienced a sharp recovery. By March of 2018, when capital flows turned, the central bank had bought close to $40 billion of reserves, equivalent to about 8% of GDP. The market understood this arrangement, and while we kept the possibility of selling reserves if needed, these silent interventions were not viewed as disruptive to our floating exchange rate system. I guess this was because it was understood that we did not time these purchases, so they were not contingent on the level of the exchange rate.

Still, I have to say that this policy of reserve accumulation turned into a bit of a PR nightmare. Reserves yield the rate of devaluation plus the return on investment, while the short-term government paper pays an interest rate in local currency. Sooner than later, most of the press (and professional consultants) started focusing on the rollover dynamic of this debt, oblivious to the fact that it was backed by foreign assets on the asset side of the balance sheet. Indeed, our liabilities were not really going up, as we were growing assets and liabilities at the same time. However, the growth in the balance sheet had a significant hedging property since assets were in foreign currency and liabilities in pesos. This implies that, if things remained calm, it may well be that we ended up paying a cost for holding the reserves in terms of interest rate differential – but, if things turned sour and the real exchange rate depreciated, then the balance sheet of the central bank would become much stronger. It is this insurance property that endows reserves with value to the central banker.

In the case of Argentina, the accumulation of reserves strongly improved the balance sheet of the central bank in the face of the negative external shock of 2018. On taking office, the net worth of the central bank was a negative $93 billion,44 This number is estimated by subtracting from the asset side of the balance sheet both Adelantos Transitorios and Letras Intransferibles, two non-marketable assets that the central bank had received in exchange for international reserves during the previous administration. testifying to the debasement of the institution during the previous government. The accumulation of reserves and the depreciation of 2018 implied that, at the time I left the central bank, this number had shrunk to a negative $42 billion, an improvement of about $50 billion. By the end of 2018, the balance sheet had improved further to a negative $28 billion. However, if nothing happens it looks as if you are paying for insurance that you don´t use. The lesson from this isn’t that you should not have reserves, but to focus strongly on communication.

The question of asset allocation

Having established the size of reserves, we can now move to the third question: in what instruments should reserves be invested? This takes us immediately to the risk/return trade-off of the allocation. My first impulse was to dramatically increase their return, moving our investments into liquid but riskier assets. This approach met the tenacious but professional resistance of the bank’s staff and led to many interesting discussions, which they always won. Of course, I did not want to push things too much.

The main concerns of the staff were liquidity and also having a sufficient buffer to be able to supply any potential need arising from the Treasury’s external debt payments so as not to force them to go to the market for large and concentrated purchases that could be disruptive of our nascent floating regime. They also did not want to expose reserves to large swings in asset prices that required the need for uncomfortable explanations, particularly if the next visit to Congress was around the corner.

These are simple ideas and most central banks apply them. But then I asked how we choose our assets specifically with regard to their hedging properties for our cashflow. I tend to remember from grad school those equations in optimal consumption theory where the whole idea of optimal consumption was to invest in instruments that provided a higher return when your marginal utility was high. Put more commonly, we needed to invest in assets that yielded the highest returns at the time when we most needed them.

Yet, when I tried to review some analytical frameworks used to think through this issue and asked for best practices to analyse the best assets that could be used to enhance the hedging properties of reserves, I found to my surprise that there were few available frameworks at hand. It is true that sometimes countries have natural hedges that reduce the need for a sophisticated investment strategy. For example, Argentina produces soybean, which tends to increase in price when the crop falls. In 2018, Argentina suffered the worst drought in 50 years, with a fall in its harvest of more than 20%. As Argentina is one of the most influential producers of soybean, its price increased by nearly 7% in the first half of the year, reducing the damage caused by the drought to our exporters and exports. This type of market adjustment may explain why some countries, particularly commodity economies, find little incentive to buy insurance or buy assets that provide hedging against these kind of shock.

However, in many cases this is patently suboptimal. For example, let’s look at the central bank of an oil-producing country. It should not be indifferent to the covariance between its reserves portfolio and the oil price. If it were running its strategic asset allocation decision between two assets with the same expected risk and return, it should be selecting the asset having the lowest correlation with the oil price. It is easy to see why. Reserves will be most needed when the price of oil is low. Likewise, it is surprising there is minimal usage of climate-related instruments to hedge against climate shocks. New Zealand has probably the most explicit mechanism for hedging, by choosing a currency composition of reserves that matches the net import in each currency. But, all in all, this remains an underdeveloped area.

Over a decade ago, Caballero and Panageas55 See R. Caballero and S. Panageas, “Contingent Reserves Management: An Applied Framework,” NBER WP No.10786 (2004). analysed the (uncontingent) reserves management strategy typically followed by central banks, concluding that the strategy of immobilising large amounts of “cash” to insure against jumps in volatility and risk aversion was clearly inferior to one in which portfolios may include assets that are negatively correlated with external shocks. Some work has been done and published with regards to the investment and hedge of sovereign wealth funds. Nevertheless, very few such discussions are found in the landscape of central banks.

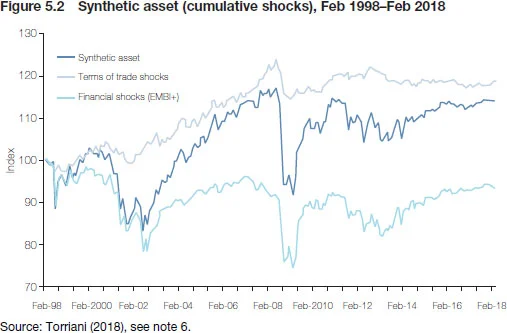

With all this framework in mind, at the Central Bank of Argentina we started to develop and build a strategic asset allocation model to optimise the allocation of our portfolio in a different risk/return framework, one where risk is not limited to the volatility of financial assets but expanded to include the volatility in the reserves’ portfolio in relation to external shocks. The way we addressed this issue was to embed in the process of optimisation a synthetic asset that emulates the shocks from external sources that affect the country´s wealth. We focused on the two most common sources of external volatility for Argentina (and Latin American economies in general), real terms of trade shocks and financial shocks, and included their impact in our asset allocation decision. We quantified these shocks into a time series of cumulative wealth shocks, and constructed a synthetic asset proportional to the size of our foreign exchange reserves, which we then detrended to avoid biases and expected returns different than zero in order to focus only on the correlation of this synthetic asset with our financial assets’ portfolio (see Figure 5.2 below).

We ran our optimisation model placing a 50% weight in the synthetic asset (that was scaled to foreign reserves size) and the remaining 50% in investable financial assets, controlling risk tolerance in our financial assets’ portfolio through a conditional value-at-risk limit. Therefore, we forced the efficient frontier to be satisfactory in the trade-off between expected return and risk, but also in terms of the diversification and hedge provided to our external shocks.66 See Mario L. Torriani, “Los Objetivos en la Inversion de las Reservas Internacionales: ¿Eficiencia en Términos de Rendimiento o de Cobertura?,” Central Bank of Argentina (January 12, 2018): https://ideasdepeso.com/2018/01/12/los-objetivos-en-la-inversion-de-las-reservas-internacionaleseficiencia-en-terminos-de-rendimiento-o-de-cobertura/.

The role of multilateral institutions

Another important step to improve the strategic asset allocation framework was our development of a forward-looking model to project expected returns and distributions. Here, we used work already done by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), but changing our framework to a factor-based approach where expected returns and distributions supporting our asset allocation decision are based on a comprehensive assessment of the underlying risk factors.

This factor-based approach is separated into three phases: factor projection, return projection and portfolio construction. During the factor projection phase, yield curves are constructed with growth, output gap and inflation as inputs, and backtesting is used to help find linkages between different sovereign business and monetary policy cycles. Factor projection is then used to estimate the asset’s expected returns, distributions and covariances, and the efficient frontier is obtained through optimisation techniques such as resampling.

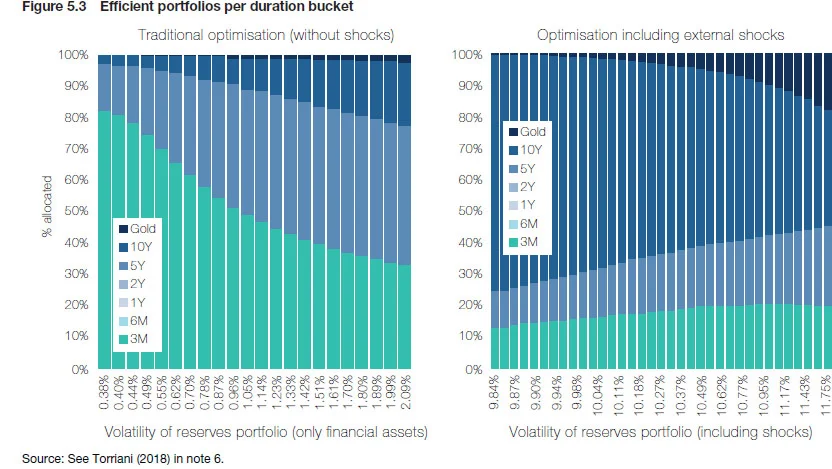

Although the general idea is very straightforward, empirical or practical implementations are rare. In fact, we have only timidly started moving to the recommendations of this broader optimisation. Central banks prefer to focus on their own balance sheet, probably because they want to avoid any headline or reputational risks. However, once you start to consider hedge properties, your asset allocation decision might drastically change. An efficient portfolio in terms of the hedge provided does not mean that it is efficient within the traditional risk/return framework, and it is probably not. However, it is the one that gives the highest coverage for your specific shocks (see Figure 5.3).

Let me share some portfolio variance results.77 Taken from Torriani (2018), see note 6. A conservative approach to minimising portfolio variance has a very high proportion of assets in 3M Treasuries, allocating there about 80% of holdings, with the remaining 20% split between 2Y, 10Y and gold reserves. However, when we try to build a portfolio that minimises risk considering the shocks faced, the composition changes dramatically. 3M Treasuries fall to about 10%, another 10% is taken up by 2Y Treasuries, with the bulk of the assets (up of 70%) going into the 10Y bond. It makes sense: the 10Y bond will likely provide a more powerful hedge to a sudden stop. Likewise with gold. In the shock responsive portfolio, the share of gold holdings increases, again because it provides a good hedge in a financial crisis. The drawback is that the value of your financial assets will have more volatility and even negative returns, depending on the hedge ratio, when there is some positive shock for the overall economy (ie, an increase in commodity prices or higher growth in the US economy).

Therefore, once you start to think about the volatility of your reserves’ portfolio, in terms of the volatility of your financial assets but also from external shocks, the covariance of your financial assets with external shocks starts to play a significant role. Needless to say, you really should have an extremely good communication policy to explain what you are doing and why.

It is here where I think there is a role for multilateral institutions to help and provide better advice to many countries: not only by building this conceptual framework that improves the hedging strategies in reserves allocation, very much in the way I have just described, but also by putting on the shelf new instruments that, although liquid, should have the correlation properties countries require. Having access to these tools would be a great improvement to our decision set. There is another advantage. By partnering with respected multilateral organisations, central banks have much larger leeway to operate and experiment with these instruments, considering that it is understood that these organisation have no other objective but the well-being of its country affiliates. This will also allow central bankers to better communicate and build trust with their populations as to the strategies that are being followed, and help explain when an ex ante rational policy becomes sour ex post. All in all, I am certain that the area of reserve management will see lots of action in the years to come!

This chapter is based on remarks made at the 16th Executive Forum for Policy Makers and Senior Officials organised by the World Bank.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: subscriptions.centralbanking.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com test test test

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com test test test