The role of reserves in Iceland’s post-crisis recovery

Sturla Pálsson

Trends in reserve management: 2018 survey results

Denmark’s move to a holistic and dynamic risk budget

Custody in 2025: a primer for reserve managers

Assessing sources of excess return: style analysis for active investing

The role of reserves in Iceland’s post-crisis recovery

Interview: Solomon Kavuma

The global financial crisis was a near-catastrophic economic event for Iceland. In October 2008, the entire Icelandic banking system, which consisted of three major banks, collapsed over a period of a few days, with additional minor institutions collapsing over the ensuing months. Around the turn of the century, privatisation of government-owned financial institutions had released a wave of aggressive growth and lending fuelled by a glut of liquidity in the global financial markets. By the time the crisis struck, the assets of Icelandic banks exceeded Iceland’s GDP ten times over. With significant maturity mismatches, and with more than two-thirds of their assets and income coming from offshore activities, and without a lender of last resort in foreign currencies, the banks were ill-prepared for such a crisis. The deterioration in liquidity and asset quality that began in 2007 forced them into administration a year later, shortly after the Lehman Brothers collapse.

This placed the Icelandic authorities in a difficult position. The government had limited ability to support the banks because of their size. The entire economy’s deposit base, payment system and credit mechanics were located with the banks, meaning that their failure would bring the entire economy to a halt, with dire systemic consequences. Furthermore, the collapse was of such a scale that a government guarantee on bank deposits would have lacked credibility.

Therefore, on Monday 6 October 2008, emergency legislation was passed by Parliament (Act no. 125/2008) enabling the banking supervisor, the Financial Supervisory Authority, to step in and take control of vulnerable banking institutions. In a decision unique to Iceland, instead of guaranteeing all deposits the government granted depositors priority status over all other unsecured creditors to the assets of the banks in case of bankruptcy, including senior unsecured creditors. The entire economy’s payment system, including guarantor of credit card transactions, vis-à-vis the rest of the world was moved temporarily to the central bank as the last remaining foreign payment agent. In addition, strict capital controls enforced by the central bank were introduced to deal with the unprecedented balance of payments problem. The capital controls would give the local economy time to restructure and recover, and prevent the significant externalities involved with the flight of enormous accumulated capital positions effectively freezing the balance of payments crisis in mid-air. This chapter now discusses Iceland’s journey of the past decade in more detail. The first section explains the balance-of-payments crisis the country found itself in. The following section sets out the role reserves played in the country’s recovery, and the lifting of capital controls. The next discusses the management of the capital flows and a final section concludes.

Balance-of-payments crisis

In November 2008, the Icelandic authorities entered into an economic programme with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), including a standby facility of $2 billion and bilateral loans from several Nordic allies for another $2 billion. The main objectives stipulated in the programme were to stabilise the exchange rate, restructure and resurrect the financial sector, and strengthen the fiscal situation.

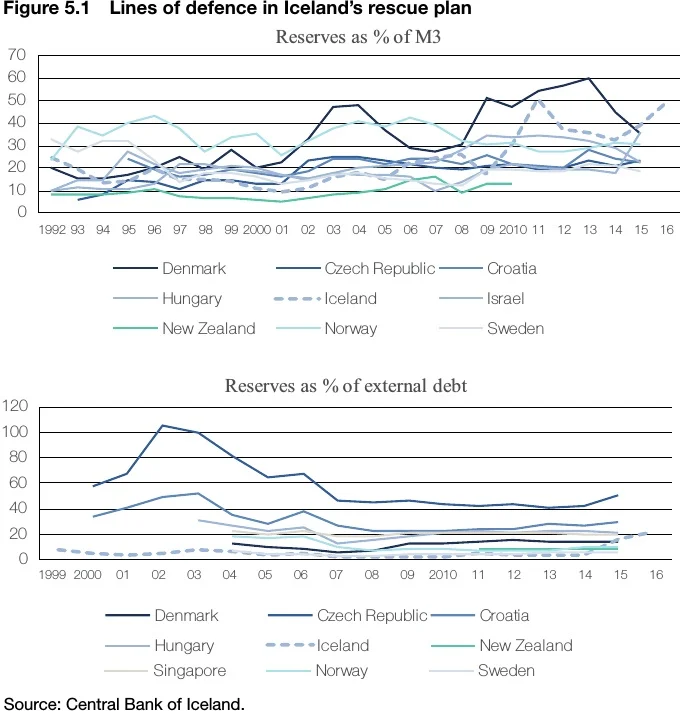

An underlying theme during the initial crisis years was to do everything possible to avoid a sovereign default and the transfer of funding obligations to the sovereign. A default would not only have been costly in terms of funding for the entire economy for many years to come, but would also have significantly prolonged and deepened the crisis, likely leading to a complete collapse of Iceland’s local and cross-border payment systems. Figure 5.1 presents the lines of defence for the rescue effort, placing the sovereign at the centre and depositors in the banks as the second line of defence. Protecting depositors was necessary not only to stop the ongoing run that was threatening to collapse the payment systems, but also to prevent a total cessation of economic activities – such as the ability to pay wages and purchase essentials.

Despite the all-encompassing nature of the crisis, a number of factors worked in Iceland’s favour early on. First, the sovereign was among the least indebted within the OECD prior to the crisis, with gross debt of around 20% of GDP at year-end 2007. Second, the economy is export-driven, and tourism and the marine sector benefited significantly from the rapid depreciation of the currency. Third, Iceland has a robust social safety net, with significant fiscal spending blunting the economic impact. Fourth, the Icelandic population, well-educated and fluent in English and the Nordic languages, could easily seek employment abroad, reducing unemployment and related social benefits costs.

Over the course of 2008, the financial crisis evolved into a catastrophic balance-of-payments problem, which did not ease with the default of the entire private banking sector. This problem, frozen in place due to capital controls, can be divided into the following four major categories.

-

-

Offshore króna: At year-end 2008, it has been estimated that liquid krona deposits and government bonds held by foreign financial institutions, largely the remnants of carry trade not held in derivatives, amounted to 41% of GDP. From a reserve adequacy standpoint this was highly unstable (and was defined as short-term debt no matter the maturity), especially in light of the bleak outlook for the Icelandic economy at that time and the significant drop in offshore króna exchange rates.

-

-

-

Winding-up banks: The initial strategy was to carve out all domestic assets and deposits from the old banks, place them in new banks, and then put the old banks into administration. However, aside from the substantial local assets still owned by the estates, the old banks retained equity or debt claims on the new banks, which did little to resolve the expected balance of payments pressure that the resolution of these local assets to their foreign claimants would entail – with amounts reaching a staggering 50% of GDP.

-

-

-

Economy-wide deleveraging: The significant risks stemming from these three categories and the state of global markets prevented local companies with foreign funding from refinancing at sustainable rates. This resulted in a steep and accelerated deleveraging process for the economy, and a drain on local foreign exchange markets. The process would have been even more dramatic, and resulted in more default, had the capital controls not provided a strong disincentive to trigger default or accelerate repayment, as all remaining recoveries would then fall under capital controls.

-

-

-

Portfolio rebalancing and capital flight: The crisis motivated local parties to run for cover and diversify out of the Icelandic economy, resulting in hoarding of foreign currency. Moreover, Iceland’s fully funded pension system was not allowed to purchase foreign assets. This caused a gradual fall in the ratio of foreign assets, and a pent-up demand for rebalancing that increased steadily over the tenure of the capital controls. Quantifying the size of the problem was complex and path-dependent, but a central bank estimate suggested 10–30% of GDP. The IMF warned of a potential drain from resident outflows, and estimated a range from 35% of GDP to as much as 170% in the case of full-blown capital flight. Nevertheless, the risk was concentrated on the downside and, without a credible strategy to deal with the first two categories, outflows could spiral out of control due to front-running incentives.

-

In all, and as a worst-case scenario, an amount in excess of 120% of GDP was likely to seek an exit through local foreign exchange markets or local foreign exchange funding, causing a freefall of the exchange rate and potential economic meltdown. The realisation and market expectation that this was the case exacerbated the risk of a race for the exit unless the situation could be diffused in an orderly manner. There were also financial stability and social stability considerations, as the entire mortgage debt market in Iceland was linked to foreign currencies, either directly (through foreign exchange loans) or indirectly (through exchange rate pass-through to inflation-indexed mortgages). As a result, exchange rate volatility had far more severe social and economic ramifications than in other countries.

Another aspect of the crisis that is important to understand is that, due to market expectations, those with revenues in foreign currency had an incentive to convert as little as possible to domestic currency, and those with expenses in foreign currency had an incentive to utilise their local currency and buy foreign currency to cover cost. The current-account surplus was therefore not representative of the actual amount of foreign currency available to the local market. With locally owned foreign assets running at a premium, there was obviously little hope that Iceland, and much less the state, could somehow fund the repayment of +120% of GDP through available foreign currency liquidity, nor was there any willingness subsidise these liquidity and exchange rate risks by layering on government debt, which was already soaring. To stabilise exchange rates and expectations, as well as restructuring and rebuilding the local economy, a strict capital control regime was put into place at year-end 2008, preventing the significant negative externalities that disorderly and market-driven capital flight would have involved. These controls were critical in providing for the orderly resolution of frozen balances through a sequenced, conditions-based strategy that eliminated the “race to the exit” expectations of the market.

Box 5.1 Iceland’s economy

Located in the North Atlantic between Greenland and Norway, Iceland is a small, open economy whose main economic activities are tourism, marine products and energy-intensive products built on Iceland’s substantial supply of hydro and geothermal power. Iceland’s level of economic development is high, with annual per capita income ranking fifth in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) at around $55,000 (adjusted for purchasing power parity, PPP). Iceland is also a member of the European Economic Area (EEA), granting it open access to the European Union (EU) single market. The country has an independent currency, the Icelandic króna, and since 2001 monetary policy has targeted 2.5% inflation and financial stability. The Central Bank of Iceland is independent by law, with a five-member Monetary Policy Committee that makes decisions on the application of the central bank’s monetary policy instruments, including its interest rates, transactions with credit institutions other than loans of last resort, decisions on reserve requirements, and foreign exchange market transactions aimed at affecting the Icelandic króna exchange rate. ■

Role and hazards of reserves

An ongoing theme in reserve management focuses on the optimal size of reserves, which is often bounded by rather simplistic ratios and metrics. In our view, the size of reserves should be determined by the scope, likelihood and size of the concerns that could call for their utilisation, with mitigations to their cost of carry. There are number of factors that have been utilised around the globe to determine optimal reserves: fixed or floating rate regimes; the size and depth of the economy; and factors such as imports, short-term debt and gauges of capital flight. It is important, however, to determine which situations would make it prudent to utilise reserves – such as the protection of the state and critical functions – and which potential risks should be tackled through regulation, capital controls, exchange rate fluctuations and default.

One of the benefits of holding a prudent level of reserves is that it bolsters a general sense of confidence, thereby reducing the likelihood of a balance of payments crisis. This can be thought of as the confidence that critical payments and debtors essential to the economy, however they are defined, will always be covered, reducing the risk to creditors of tertiary debts. A crisis of core components can quickly erode confidence in the entire economy, accelerating redemption and leading to capital flight.

A sizable reserve buffer that gives creditors confidence can also foster moral hazard, however, and can encourage even riskier behaviour by financial institutions, which are often thought of as core components. The perception that the state’s reserves are a form of insurance can catalyse greater risk-taking, precipitating the need for more reserves, etc. In many such cases, using the reserves would simply transfer a private blunder to the public balance sheet. This can reduce the creditworthiness of the state, which as a benchmark increases the cost of credit for the whole economy.

Moreover, the cost of holding adequate reserves based on classical measures can be extravagant if there is a negative carry between the home currency and reserve currencies. The cost of insuring the risk emanating from certain sectors of the economy can therefore be a significant burden on public finances. Where significant reserves are required, it would seem reasonable that those generating the need for reserves should share in the cost of maintaining them. In Iceland in 2008, the Central Bank of Iceland’s liquid reserves covered less than 10% of the banks’ short-term debt, and were therefore woefully inadequate to imply any practical coverage of short-term debts emanating largely from the financial system. Even so, it is difficult to envision that any sensible level of reserves would have been sufficient to prevent the crisis, nor that the maintenance and use of such reserves would have yielded an acceptable outcome in this particular case.

Therefore, as regards the role and size of reserves, it is important to identify the potential situations that would justify their use, and not imply that the reserves can be used as a backstop for debts that should not call for their use. The Icelandic case highlights a situation where classically adequate reserves and their use to backstop a failing financial system would probably have resulted in an intolerable public burden, and where other tools can be utilised to mediate the crisis at hand. The Icelandic example also highlights the fact that other measures, apart from reserves, should have been in place to prevent such a build-up of risk in the first place regarding cross-border banking, regulation and supervision. Many of these measures have since been introduced or improved.

Role of reserves in the Icelandic recovery

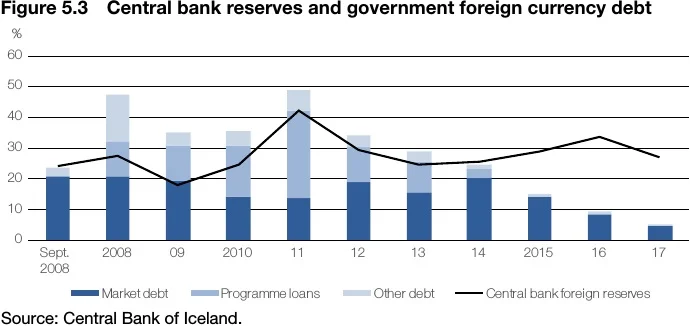

Having outlined the immediate impact of the crisis, this section discusses the role of reserves in the recovery. After the Icelandic króna was floated in 2001 and an inflation target introduced, the authorities largely pursued a hands-off policy in relation to the local foreign exchange market. Intervention was conducted according to a pre-announced schedule to service government foreign currency debt, and when reserves exceeded foreign debt in 2004 the regular intervention programme was scaled back significantly. The Republic of Iceland’s Aaa/AA3 (Moody’s/S&P) credit rating supported an open and continuous access to global capital markets. The central bank’s limited reserves did not seem to be cause for concern for the rating agencies, further strengthening the rationale behind the hands-off approach and small reserves (see Figure 5.2).

Through the years, Iceland did not have a specific target for optimal reserve size. As a target for a minimum size, a three-month import rule had been used. Other informal measures, such as the Guidotti–Greenspan rule of a 100% short-term debt cover for the economy and the size of the reserves relative to the size of the economy (ie, GDP), were also monitored. As the local banks grew larger, Iceland reached as little as 10% cover according to the Guidotti–Greenspan criteria, but the reserves never fell below the import rule and, compared to other small open economies, the reserves-to-GDP ratio seemed in line (see Figure 5.3).

Well before the crisis hit, it was apparent that the reserves were not sufficient to save or backstop the banking system, although limited attempts were made to reduce them even further. Faced with the mounting liabilities associated with resurrecting a new banking system, the UK and the Netherlands demand for a state guarantee on deposits in Icelandic bank branches within their jurisdiction and a line of desperate bank creditors demanding repayment, the state was forced to prioritise in order to retain its own creditworthiness and maintain a functioning payment system. Without this, a viable recovery was unlikely, and without the state’s creditworthiness, other major debtors in Iceland would not regain global market access, increasing further the probability of default.

To this end, building foreign exchange reserves to a prudent level was a priority, and $5 billion was secured as a part of the IMF economic programme. Establishing the market expectation that the state had sufficient firepower to cover its own commitments and maintain a functioning payment system was seen as a requirement for the resurrection of all other economic variables. Preparations for regaining access to global capital markets began with the design of a new medium-term debt strategy for the state in cooperation with the IMF. An extensive programme of investor meetings was held to inform investors about what had happened, and what the prospects were for future economic development. Of paramount importance was the perception that the state was prioritising through the use of capital controls to the extent required to service such commitments and maintain reserves.

The country issued its first post-crisis public bond in 2011, a five-year $1 billion issue, followed by a ten-year $1 billion issue a year later. This established the foundation for other parties to begin restructuring and extending their debt profiles, as it provided a benchmark for other local issuers to follow. This included state and local power companies bearing sizeable state guarantees.

Through foreign exchange purchases in the local market and the issuance of global market bonds, the state intended to eventually replace all IMF-related funding of the reserves with market funding. In 2014, a €750m bond was launched and the proceeds used to prepay the remaining IMF programme-related debt. Iceland only utilised the foreign bond market to strengthen the reserves and repay the state’s foreign debt, as fiscal funding needs were financed through the local Treasury market.

Iceland’s initial response to the crisis can be summarised as follows.

-

-

Utilise capital controls to freeze all capital transactions, rebuild reserves and repay debt, and allow solvent local entities to service foreign debt. The repayment of defaulted or accelerated debt was locked behind capital controls.

-

-

-

With the support of the IMF programme and rebuilding of reserves, the state aimed to regain access to global markets, building upon the trust that reserves would be maintained and market access would be prioritised as needed.

-

-

-

This paved the way for market access for large corporations, smoothing their repayment profiles to manageable levels.

-

Only once this was prioritised and established were there any grounds to begin resolving other aspects of the overhang frozen by capital controls. The terms and pace was defined largely by the effect it would have on reserves. In this respect, the argument regarding the required size of reserves became central to the liberalisation process.

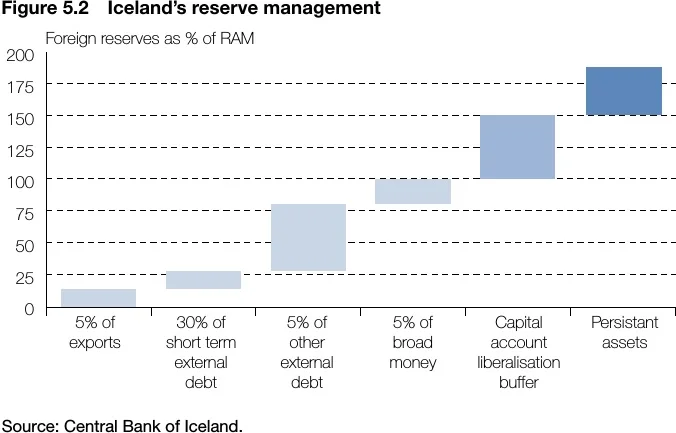

Deciding the optimal/prudent level of reserves is challenging. Quantifying how large a reserve buffer to hold against different risks and challenges also necessitates measuring the benefits against the opportunity cost of holding reserves. In addition, the size of the reserves became a significant point of contention, as creditors and stakeholders argued for the accelerated release of funds. For guidance, Iceland turned to the Assessing Reserve Adequacy (ARA)/Reserve Adequacy Measure (RAM) analytical framework proposed by the IMF.11See IMF, “Guidance Note on the Assessment of Reserve Adequacy and Related Considerations” (June 2016), https://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2016/060316.pdf. Utilising the RAM metric as the basis for the reserve adequacy was extremely beneficial for a number of reasons.22For a particular economy, the RAM number equals the sum of 5% of exports, 30% of short-term debt, 15% of other external debt and 5% of broad money. In the case of Iceland, all offshore Icelandic krona positions and foreign holdings of liquid Icelandic krona assets such as deposits and Treasury bonds were considered short-term debt. Broad money is a measure of the ability of local residents to exchange liquid krona assets for foreign currency and head for the exit. An advisable range for foreign exchange reserves is set by the IMF as 1–1.5 times RAM.

-

-

Iceland’s adherence to the RAM standard placed the country in line with the IMF’s expectations and forecasts, with minimum reserves becoming a baseline tracking indicator for the liberalisation process. In this regard, positive Article IV assessments were a factor in improving sentiment locally and in global markets.

-

-

-

As an important authority in financial markets, the IMF provided credit rating agencies and creditors with a baseline expectation for reserves. Iceland’s adherence to such levels throughout the liberalisation process was a factor in building credibility and market access.

-

-

-

Utilising a metric provided by an independent third party with immense financial market authority provided Iceland with an undisputed baseline from which to conduct discussions with stakeholders. Any resolution or liberalisation process whose risk parameters put these metrics in jeopardy would be denied. This was imperative in keeping discussions on track.

-

-

-

Economic fundamentals improved dramatically under the protection of and in spite of capital controls. The sequenced liberalisation process where all stakeholders and market participants agreed that reserves based on the RAM metric were more than sufficient for the general liberalisation process to proceed, local and global market sentiment improved to the extent that the impact of eventual liberalisation on markets was barely noticeable.

-

Managing control flows

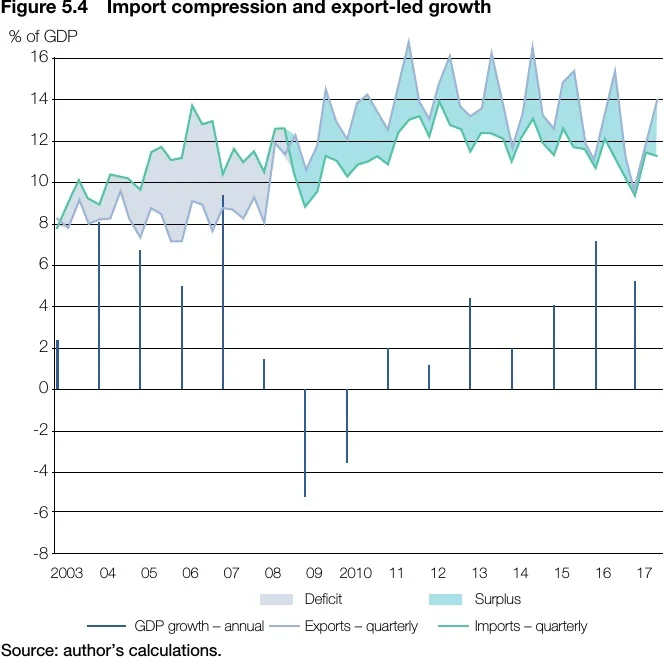

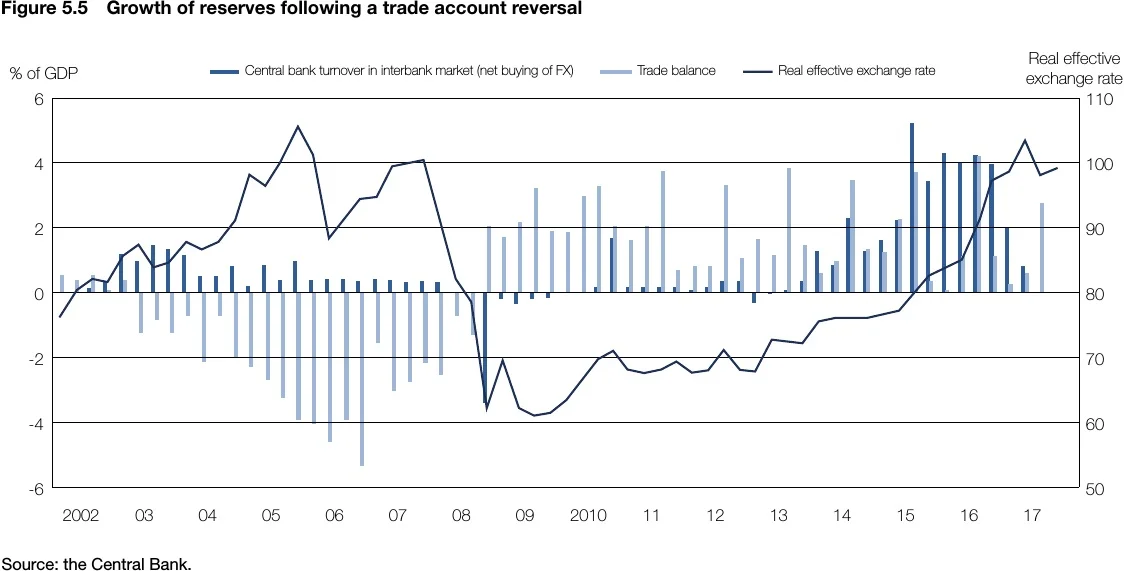

The króna depreciation at the height of the crisis caused a sharp turnaround in the current account balance. The real exchange rate rose sharply between 2002 and 2006, and remained strong in 2006 and 2007, with increased volatility. A significant current-account deficit opened up, but the currency depreciation in 2008 turned the deficit into a sizeable surplus that remained through 2017. The economy started growing again in 2011, after losing roughly 10% of GDP in 2009 and 2010.

The Eyjafjallajökull volcanic eruption in 2010 raised concerns within the tourism sector, and an advertising campaign was launched globally to attract more visitors to Iceland. Due to a multitude of factors, tourism has since grown from generating 15% of external revenue to 35%, and remains the fastest-growing sector of the economy. The associated inflows undoubtedly contributed to the successful winding-up of the failed financial institutions and to the reduction of the offshore króna stock from roughly 40% of GDP to the current 3% of GDP. Iceland’s net international investment position is now positive for the first time in 70 years, after being negative by 130% of GDP at the height of the crisis (see Figure 5.4). Gross government debt was 36% of GDP at year-end 2017, down from 91% in 2011.

The Central Bank of Iceland stepped up its purchases of foreign currency in the local market in 2014. A strong current-account surplus, driven by robust growth in tourism and favourable terms of trade, helped to bolster reserves and retire foreign-denominated debt. At the same time, preparations for lifting capital controls were well underway. Intervention slowed the appreciation of the Icelandic króna and reduced the probability of disorderly outflows after the liberalisation of capital outflows. Once the major legacy balance of payments challenges had been addressed, ample reserves built up and foreign government debt significantly reduced, the stage was set for liberalising the capital account (see Figure 5.5).

Iceland lifted all restrictions on capital outflows in March 2017. As expected, the foreign exchange market saw increased volatility in the ensuing weeks; however, volatility subsided in the second half of 2017 and the central bank has largely refrained from intervening in the market. The authorities had prepared for a worst-case scenario, but favourable economic developments locally, supported by factors such as growth in tourism and low oil prices, contributed to a successful liberalisation process.

The local pension funds have been the largest investors in the economy, with total assets around 1.5 times GDP, a quarter of them foreign assets. The pension funds’ long-term foreign asset target ranges from 40% to 50% of total assets. Expensive foreign equity markets, tight credit spreads and a wide interest rate differential reduce the pace at which the pension funds rebalance in favour of foreign assets. A price correction and a reduction in the positive carry for holding domestic assets could accelerate the speed of the rebalancing. It is therefore prudent for the Central Bank of Iceland to hold reserves well above the minimum level, as it could take the pension funds between five and 15 years to meet their long-term target. Local pension fund assets are predominantly long-term domestic bonds and foreign equities, mostly in euros and US dollars.

Capital inflows were restricted by a special reserve requirement (SRR) introduced in 2016. The purpose of the SRR was to prevent the accumulation of new krona balances prior to and over the course of the general liberalisation of outflows, and to ensure effective transmission of monetary policy. The SRR rules require investors in interest-bearing króna assets to hold 40% of the total investment in a special reserve account at 0% interest for one year. The rules also play a role in shaping capital inflows, as they affect long-term capital much less than short-term or leveraged capital. The rules on the SRR are now under review by the central bank. Given that the interest rate differential is currently 3–4%, relaxation of the reserve requirements would probably attract capital inflows. Iceland is at a different place in the business cycle than most of its trading partners, and has been running tight monetary policy to prevent the economy from overheating. In the long run, a fully liberalised capital account should further integrate Iceland into the global economy and align the business cycle, reducing the need for capital flow management tools such as the SRR.

Conclusion

The crisis in Iceland was caused by the rapid build-up of foreign exposures in the local banking system and the associated inflows of capital, which eventually dried up and drove the system into bankruptcy. A number of measures have been taken to prevent external imbalances from causing similar problems in the future. Capital and liquidity requirements in the banking system have been increased, and more importantly, the net stable funding ratio requirement makes it impossible for Icelandic banks to accumulate large maturity mismatches in foreign currencies. Many other legal requirements for the system have been strengthened as well.

Reserves have been significantly improved at the Central Bank of Iceland, and are funded domestically for the most part. The ability of the central bank to prevent external imbalances from jeopardising domestic financial stability is therefore much enhanced. Although no “sensible” level of reserves would have prevented the financial crisis in Iceland in 2008, given the current legal framework and the strong reserve position, a repeat occurrence of such a catastrophic episode is considered unlikely by local and external observers.

Reserves play the role of an insurance policy for external imbalances, but they carry opportunity cost and risks, many of which were highlighted before and during the financial crisis. While sizeable reserves after the crisis have bolstered confidence in Iceland’s ability to deal with unexpected events, they also bear a significant fiscal cost and could foster moral hazard, with short-term investors seeing them as a credible foreign exchange and liquidity backstop. Defining the appropriate role, size and optimal use of reserves is therefore an ongoing project in Iceland, and one that continues to be a key element in establishing a sustainable path for economic development in our small, open economy.

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the Central Bank of Iceland.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: http://subscriptions.centralbanking.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com