Emerging market debt during interest rate increase cycles: analysis for reserve managers

Luther Bryan Carter and Michael Cross

Emerging market debt during interest rate increase cycles: analysis for reserve managers

Trends in reserve management 2021: survey results

Reserve management in China: foreign reserves, renminbi internationalisation and beyond

Emerging market debt during interest rate increase cycles: analysis for reserve managers

Interview: Jarno Ilves

How the Fed’s Fima addressed the 2020 dollar liquidity shortage

How derivatives can add value to modern reserve management

At the heart of reserve management is the principle that the safety and liquidity of the reserves come before their return objectives. Although in reserve management the “search for yield” is nothing new, a “requirement for yield” is. Years of declining yields on traditional reserve assets, in many cases to near zero or even negative, have forced reserve managers to rethink their tried and trusted methods. With zero or negative returns, merely holding sovereign bonds arguably no longer meets the “safety” criterion as capital is eroded.

As a result, reserve managers have looked elsewhere: from rejuvenating gold as a reserve asset to buying equities and property. This diversification has included emerging market bonds, a move supported by the burgeoning internationalisation of the renminbi, a reserve currency issued from an emerging market jurisdiction. While they may not all reveal their holdings, the evidence for this move is there. In the survey published in HSBC Reserve Management Trends 2020, for instance, 23 reserve managers with an average holding of $26 billion stated that they already invest in this asset class – notably a group made up mostly of middle income countries. A further 20% of respondents indicated they would consider investing in emerging market bonds (above BBB) in the next five to ten years.11 See page 49 in Pringle, R. and N. Carver (eds), HSBC Reserve Management Trends 2020 (London: Central Banking Publications, 2020).

For the yield-starved reserve manager the attractions are obvious: it is sovereign paper and increasingly strongly rated, and with liquidity also increasing the return above, say, G10 paper, is significant. Yet so too are the risks, not least at a time when, as of April 2021, interest rate expectations in the US are rising. The dominant role of the dollar as a reserve currency naturally impacts the narrative on how the economic and investment landscape may evolve.

For any central bank, a move into emerging market debt will require extensive analysis of the unique risk factors to investing in respective asset classes in the wider context of the strategic asset allocation, and certainly in line with central banks’ portfolio mandates. Nevertheless, we feel there is an opportunity for some shared learning across the asset class with the reserve manager firmly in mind.

This chapter therefore delves into some common considerations for central banks looking at emerging market debt. The chapter is structured around three questions we think will resonate with reserve managers. First, how does emerging market debt perform in different interest rate cycles? Second, what is the decomposition of return factors: spreads, duration, convexity, foreign exchange, and their various sensitives to rising dollar rates? Third, what happens to credit quality as global liquidity supply tapers and eventually reverses? To begin with, however, a discussion of the fundamentals associated with emerging markets will be helpful.

Emerging market debt: backdrop, dynamics and dependencies

Emerging markets are irrefutably dependent on interest rates and liquidity conditions in developed markets. Despite diversifying their sources of funding and building liquid local debt markets over the last two decades, emerging markets remain at the whim of major economy bond market dynamics and central bank monetary policy decisions in terms of their ability to access capital markets, their average cost of borrowing, relative currency valuations and, frustratingly, sovereign credit ratings. Counterintuitively, the increased frequency of global macro events in recent years may well have served to increase the role of the US Federal Reserve as “the world’s central bank”.

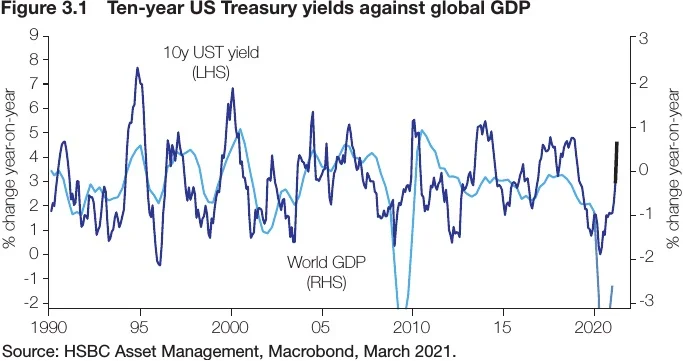

The economic shock and global recession caused by the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 pushed interest rates in many countries, including emerging markets, to historic all-time lows. In response to decisive action from governments and central banks, economic activity bottomed early in 2020 and began to recover sharply in the second half of the year. Interest rates have generally lagged this move. In 2021, as vaccination efficiency has increased and access to vaccines improved around the world, bond markets are beginning to incorporate expectations of higher inflation, removal of quantitative easing, and eventual interest rate normalisation.

The academic literature is replete with studies on the effects of such interest rate cycles on emerging markets. Jeffrey Sachs, Ricardo Hausmann, Kenneth Rogoff and Carmen Reinhardt are but a few of the many well-known authors on this topic that have examined the role of the global monetary cycle on debt crises, banking crises and currency crises.

How do emerging market bonds behave in interest rate cycles?

Against this backdrop, we turn first to investment in emerging market bonds as an asset class and the repercussions of interest rate cycles on their valuations. The US business cycle has become a longer and more continuous function over time. Since 2000, the Federal Reserve has only raised interest rates in two relatively slow and well-telegraphed monetary tightening cycles. As markets are prone to shifting expectations and false starts in predicting central bank decisions, there are many more instances of significant rises in bond yields. By our count, US ten-year bond yields have risen by approximately one percentage point seven times since 2000. In this analysis, we will also consider the larger group of observations as these can have a profound impact on reserve valuations and forward income expectations.

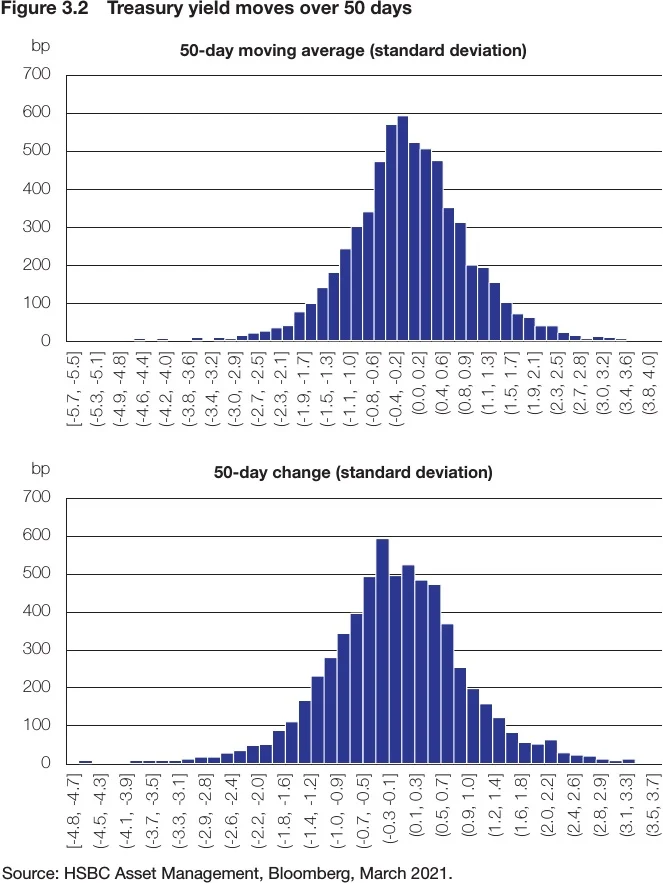

What drives interest rates is a complex combination of economic growth and growth expectations; inflation and inflation expectations; monetary policy and policy expectations; and technical factors such as the supply of Treasuries, asset allocation demand, investor positioning and the issuance calendar. The combination of these inputs results in a distribution of Treasury yield moves exhibiting right skewness and low kurtosis, as expectations around the macro cycle tend to the positive, except during periods of economic deceleration or recession when data shift in unison to an adverse equilibrium (see Figure 3.2). In short, Treasury yields tend to move down quickly and up slowly, meaning that periods of rising rates are usually slower and more protracted.

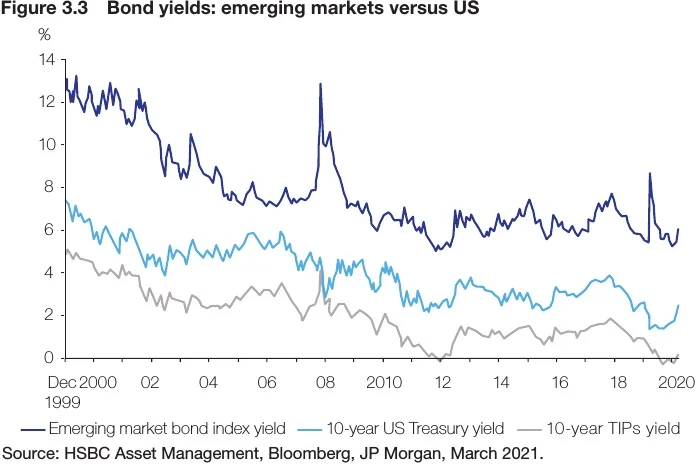

How does emerging market debt behave in such periods? There is no single, prescribed answer to that question – for instance, in some periods rising US yields have coincided with positive returns in emerging bonds and currencies. However, on average, emerging assets have posted negative results during interest rate increase cycles. Emerging bond returns tend to be fairly uncorrelated with US Treasuries at only 9% average daily co-movement over long periods of time. However, during stress periods that correlation rises to an average of 16%. The correlation with US real yields is higher at 24%, increasing to 70% for stress periods. During drawdowns in the asset class, in particular, the high-yield sub-index shifts in behaviour, becoming positively correlated with Treasuries in contrast to the usual negative correlation. Knowing when a rate rise cycle is underway turns out to have a meaningful impact on the behaviour of the asset class (see Figure 3.3).

Key components of return during rate rise cycles

The intuition here is clear: the “risky” component of emerging bonds, the credit spread, generally acts as a buffer to the safe haven of underlying Treasury duration. In a typical market environment, moves up in Treasury yield are absorbed by the spread component of return, particularly if they are due to positive economic factors. For high-yield bonds, the spread component dominates return such that the influence of underlying Treasury yields is often trivial.

However, during rate rise regimes, the factor set is more adverse to borrowers: inflation rising and central bank tightening can dampen the credit outlook and lessen the issuer’s credit profile. In these environments the buffering effect of credit spreads ceases to function, and the return from duration, return from spread and return from convexity all move in the same direction. On tallying these instances historically, we found that the negative effects of rate rise cycles on the emerging market asset class break down as shown in Table 3.1. In transpires that cycles in which real interest rates are rising (not just nominal rates) tend to characterise the set that trigger emerging market debt losses, and specifically among those it is the largest rate rises in magnitude that have been the most punishing historically. Excluding these events, smaller rate rise cycles on average have proven benign to the asset class.

| Nominal rate rises | N = | Average days | Duration | Spreads | Convexity | FX |

| Small rate rises | 15 | 27 | –4% | 1% | 0% | 0% |

| Large rate rises | 5 | 24 | –4% | 1% | 0% | 0% |

| Real rate rises | N = | Average | Duration | Spreads | Convexity | FX |

| days | ||||||

| Small rate rises | 13 | 23 | –3% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Large rate rises | 4 | 38 | –6% | –8% | –1% | –5% |

| Source: HSBC Asset Management, Bloomberg, JP Morgan, March 2021 | ||||||

Much has been written about the difference between US rate rises that are led by inflation expectations versus real interest rates, including a cacophony of sell-side reports over the past few months.22 See André de Silva, “EM Action: Directionality of EM EXD Spreads,” HSBC Global Research (1 March 2021); Barclays, “Getting Real About Rates,” Credit Research (26 February 2021); Jim Reid, “Yields & Credit Spreads – The Long-term Relationship...,” Credit Strategy: IG & HY Strategy, Deutsche Bank (3 March 2021); J.P. Morgan, “Crisis Watch XXXVIII: Mind the Gap!,” Global Credit Research (4 March 2021); Kasper Bartholdy, Daniel Chodos, and Nimrod Mevorach, “Emerging Markets in a World with Rising US Treasury Yields,” EM Strategy Weekly, Credit Suisse (24 February 2021); Regis Chatellier, “Macro-strategy Themes/Hard Currency Debt: EM Sovereign Spreads are Meant to Rise,” Oxford Economics (2 March 2021). The dramatic increase in US Treasury yields to April 2021 is a case in point: in the first quarter, US rates repricing occurred in two stages – the first almost entirely due to inflation expectations, and the second almost entirely due to real interest rates. This has given birth to an array of theories, assumptions and marketplace expectations.

Our own analysis suggests that the second variety – real interest rate increases – is far more damaging to emerging market bond returns. The causality here is straightforward: while inflation as a general phenomenon typically represents earnings or revenue growth in a strong economic backdrop, benefitting sovereign and corporate issuers alike, real rate increases often represent the macroeconomic risk of over-heating and a countercyclical effort on the part of authorities to tap the brakes on the economy and reduce the stimulative impulse. When US rates rise swiftly as part of a genuine interest rate tightening regime, the accretion to returns is markedly negative.

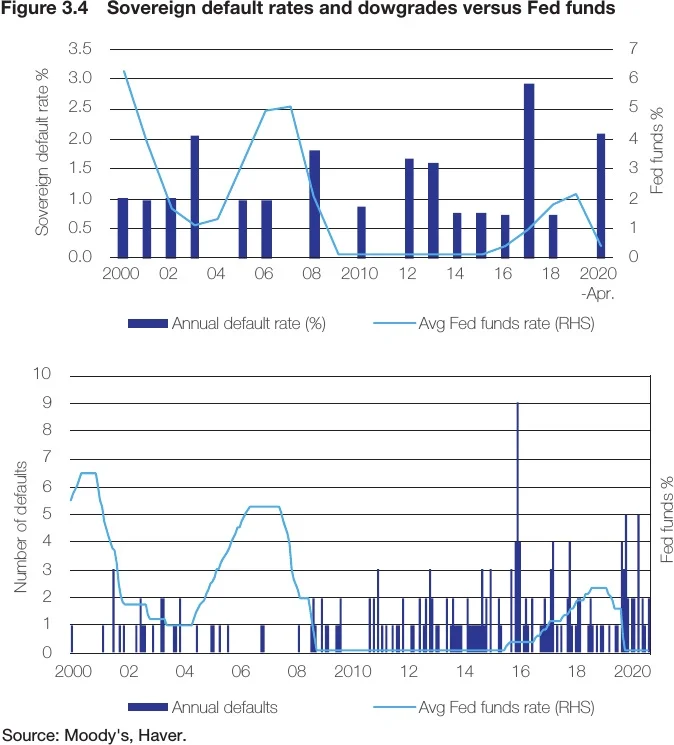

Interest rates feed credit ratings in a way that is stronger than many might expect. There is a self-reinforcing effect here that enables this pattern. During periods of interest rate increases, ratings downgrades for emerging markets issuers – particularly sovereign issuers – tend to pick up, and the incidence of default is much higher. Although ratings agencies generally claim that their ratings are blind to monetary or economic cycles, they inevitably grade issuers on metrics that are indirectly cyclical: fiscal balances, external accounts and quality of spending. As a result, rate increase cycles correlate strongly with ratings downgrades and default incidence (see Figure 3.4).

The exception to this historical pattern was the 2005–07 cycle, in which emerging markets generally tended to avoid downgrades and there were almost no defaults. We ascribe this in large part to the debt relief initiative that immediately preceded this period, absolving the debt of most of the poorer countries and allowing a prolonged cycle of re-leverage and growth. Furthermore, this was a period of high commodity prices, buffering external accounts and reserve adequacy for many of the commodity-intensive emerging countries.

What about local currency markets?

Turning to local markets, we find even higher sensitivity between cycles of significant US interest rate increases currencies, with the average cycle leading to periods of dollar strength relative to emerging market foreign exchange. The currencies of countries with lower ratings and that typically offer higher carry are not better protected; in fact, high beta currencies tend to be most susceptible to the shifting funding costs in developed markets. A counterintuitive but clear result is that no interest rate parity relationships hold: as interest rates rise on the US side, its currency strengthens; and as emerging market central banks echo those rate rises in the local markets, their currencies historically have equilibrated. The relationship between developed and developing market interest rates has often been symbiotic: historically, as the US began tightening policy rates, emerging market central banks often followed suit in some sort of unison. The tightening acted as a buffer to the downside, injecting carry that helped compensate investors for the additional volatility.

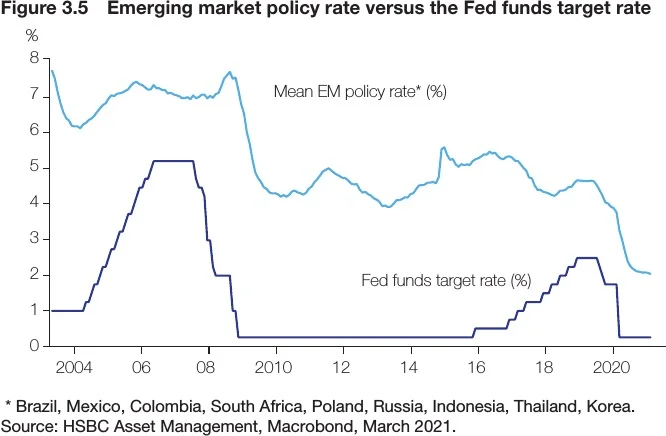

This relationship began to break down during the structural disinflation of the past decade, with deepening local liquidity and independent money supply dynamics taking a dominant role (see Figure 3.5). Many emerging markets experienced a protracted period of low inflation even after their currencies devalued during the global trade slump of 2014–15. By the time the Federal Reserve hiking cycle commenced in December 2015, emerging market central banks largely refrained from following suit and, for the first time in history, the average emerging market policy rate actually declined while the Federal Reserve proceeded with its tightening campaign. This inevitably led to further currency weakness that, in a sense, helped recompense emerging economies for the growth loss from tighter global financial conditions.

This is not just a portfolio flow effect: emerging markets currencies seem to tee off of the behaviour of other risk assets. Another finding of our analysis is that currencies tend to mimic the returns of high-yield bonds. In rate rise cycles in which high-yield credit is well-behaved, currencies exhibit a higher hit rate of positive returns. Conversely, when high-yield credit bends under the weight of higher US interest rates, emerging market currencies nearly always lose value.

There are many other considerations that play a role in the returns of currencies: the dollar cycle, commodities prices and fiscal/debt policies to name a few. For the purposes of this analysis, we treat these as endogenous to the aforementioned factor set: global growth and growth expectations, inflation and inflation expectations, monetary policy and policy expectations, and technical factors.

Conclusion

Emerging market debt assets do not always post negative returns during US rate hiking cycles. However, as we have shown, this is often the case. Contributing factors to an increased likelihood of negative returns include whether US real interest rates rise faster than inflation expectations, and the magnitude of the move in US Treasury yields. Emerging market assets are further impacted according to the degree of sub-investment grade credits, the effect of the global macro cycle on emerging country ratings, and the reaction function of emerging market central banks in response. We have demonstrated there is still a heavy interrelationship between emerging market bond yields and developed market monetary cycles, despite the growing depth and sophistication of local markets.

Among the sources of return, this analysis has demonstrated that underlying duration is most closely intertwined with US Treasury yields, with returns to credit spreads second in importance for total mark-to-market, and bond convexity a distant third. Currencies, when added to the equation, are also extremely sensitive to US interest rates and the US dollar cycle. Although these four sources of return have relatively low correlations during normal periods, these correlations rise during periods of rapid yield rise, exacerbating marked-to-market losses.

Although reserve managers rarely employ hedging strategies, the analysis presented here does reinforce the inference that such an overlay would prove sensible during stress periods. At interest rate inflection points, a simple duration hedge also acts to offset risks from spreads, convexity and currencies. The length of interest rate repricing periods depends notably on whether the increase is due to a genuine initiation of monetary policy tightening, or simply a shift or over-reaction in market expectations that may later reverse.

The adoption of emerging market bonds as a reserve investment by central bank managers has been a long and gradual evolution. We fully expect the trend of additional investment to continue and the set of countries deemed eligible for reserve inclusion to increase over time. As such, the theme of emerging market debt behaviour should continue to prove relevant to reserve managers.

Only users who have a paid subscription or are part of a corporate subscription are able to print or copy content.

To access these options, along with all other subscription benefits, please contact info@centralbanking.com or view our subscription options here: subscriptions.centralbanking.com/subscribe

You are currently unable to print this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

You are currently unable to copy this content. Please contact info@centralbanking.com to find out more.

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (point 2.4), printing is limited to a single copy.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com test test test

Copyright Infopro Digital Limited. All rights reserved.

You may share this content using our article tools. As outlined in our terms and conditions, https://www.infopro-digital.com/terms-and-conditions/subscriptions/ (clause 2.4), an Authorised User may only make one copy of the materials for their own personal use. You must also comply with the restrictions in clause 2.5.

If you would like to purchase additional rights please email info@centralbanking.com test test test